I have been thinking about writing a couple of blog posts about pre-Christian coinage for a long time, and I have been putting it off for a long time. We are certainly facing the most complex and difficult topic that can be written about Basque coinage. On this topic, and about the ethnic groups and inhabitants of the territories that minted these coins, there are more doubts than certainties. And if we add the origin and first manifestations of Basque to this topic, the results plunge us into the need for highly complex analyses.

We need experts to develop the analyses, experts who work in different fields, numismatists, archaeologists, linguists and historians. I myself am not an expert in any of these fields, I am an engineer and as a result or deformation, I tend to prefer a rather "academic" approach... those who have worked on these issues for many years.

However, it is quite possible that this entry, or its successors in the same time zone, will have some flaws or need improvement in the future; you know, as the motto of this blog says, "remember the good things said and forgive the bad things said."

The territories of Aquitaine, located south of the Garonne River, and the territories located north of the middle reaches of the Ebro River and in the surrounding area, share many common characteristics in the centuries before and after the arrival of the Romans. Among these common characteristics, they share the fact that they are the first places to display the remains of the ancestors of the Basque language.

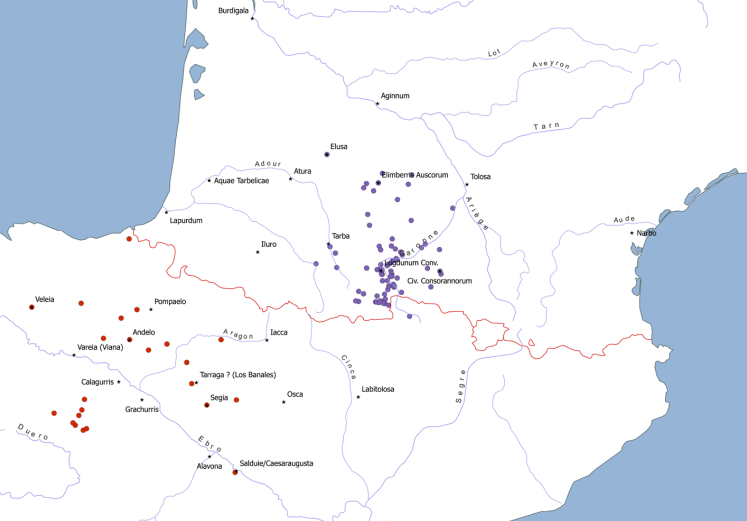

The occurrences of ancient Basque anthroponyms in inscriptions from the Roman period (republican and imperial periods) collected by Joakin Gorrotxategi – In blue in Aquitanian, in red in Vasconian

Among these possible first epigraphic traces of Basque we can mention the Paleo-Hispanic coins minted between the Ebro and the Pyrenees. But before the minting of these coins, starting from the 3rd century BC, there was already minting in the Aquitaine territories south of the Garonne. And we will look at these coins today, before looking at those from the south in a later article.

Historically, Spanish state researchers did not pay much attention to the coinage of the northern Pyrenees. For the French state, however, the southern ones were not a high priority and, if we look at the coinage of Aquitaine, it did not attract the same attention as the Gallic Celtic specimens.

We Basques, as the name suggests, who have the capacity to use Basque, do not need these limitations; fortunately, our language has managed to survive in a small area in both Aquitaine and the north of the Ebro (although it has been and will be very close) and we can look at both sides of the Pyrenees with peace of mind. Likewise, in recent years, this previous picture has begun to change completely and French and Spanish experts have been working together on the study of relations in the Pyrenees. The analysis of Aquitaine coins has been greatly deepened in the last decade under the guidance of Eneko Hiriart, Laurent Callegarin and other researchers and experts.

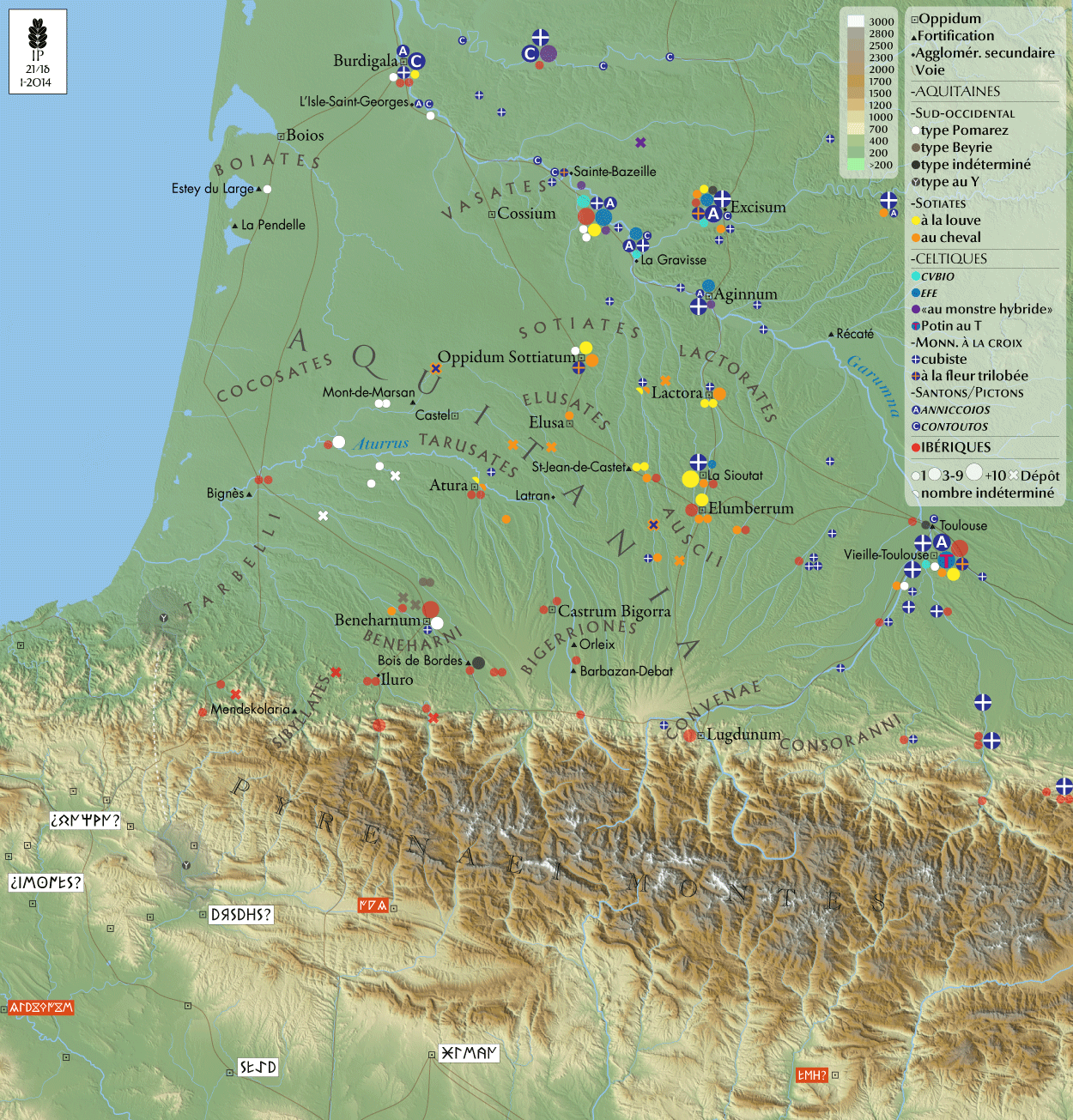

Map of Aquitaine showing the location of finds of Aquitanian ethnic groups and different types of coins

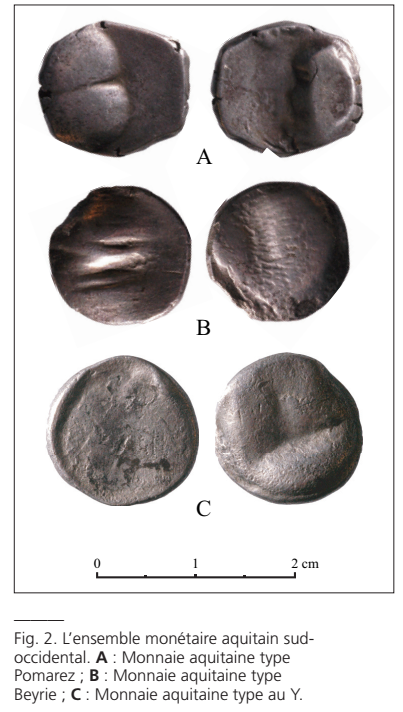

Starting from the territories of the present-day Northern Basque Country, we can find the convex coins of Aquitaine, in the Greek Y, with the different series of Beyrie and Pomarez. These coins have neither images nor textures. They are the first steps in the history of our coinage of heavy silver pieces that present stamped marks and deformations.

The location of the production of these specimens can be placed closer to the territories between the Aturri River and the Pyrenees. Historically, it has been said that they were the work of the TARUSATES ethnic group, but today, the name of the “southwestern Aquitaine” coinage is gaining ground. In fact, the Beyrie series are located around the present-day Biarritz city of Lescar, formerly called Beneharnum, which would place them in the territories of the Beneharni ethnic group. In the case of the Pomarez series, the production area is closer to the territories of the Tarusates (in the area of present-day Akize) but the participation of the Tarbellites is not excluded either. In the case of the Greek Y series, the finds are very scarce but the production area is assumed to be around the territories of present-day Northern Basque Country.

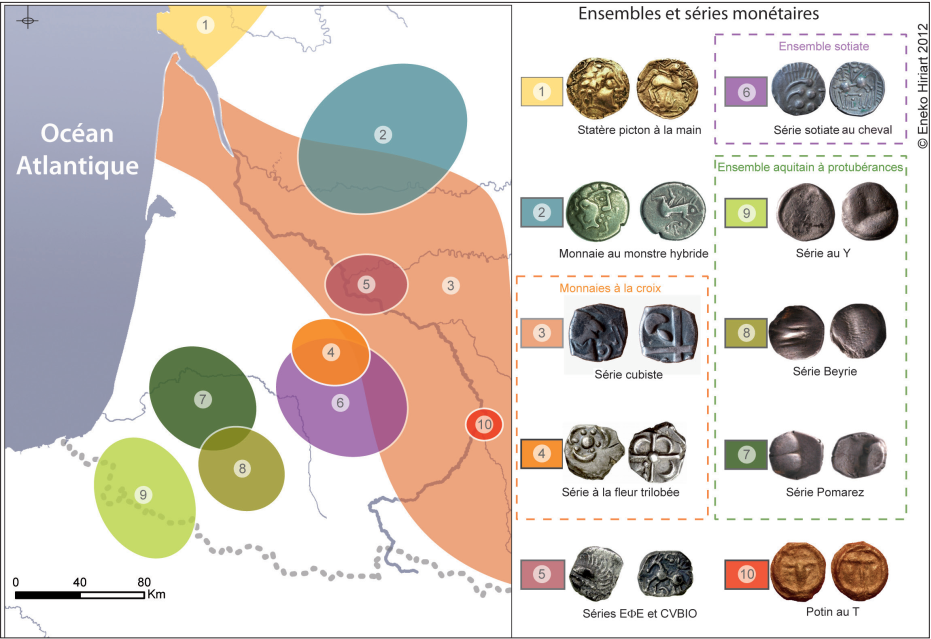

Summary of the classification of coin concords compiled by researcher Laurent Callegarin

In the case of the Greek Y series, the finds have been made in the Northern Itsasun, the Southern Sangüeza area and Fraga in Huesca (21 pieces), all very limited to the present day. The pieces of this series present an average silver weight of 4.30 grams (with a diameter of about 15 millimeters). Based on the average weight, we can place them at the end of the 3rd century BC, perhaps just before the start of the Second Punic War (218-202 BC). Through metrological analysis, these coins would be comparable to the standard coinage weight of the drachma of Emporion and Rhodes.

The first specimens of the Beyrie and Pomarez series would be close to the Greek Y series, probably somewhat more recent, that is, between the end of the 3rd century BC and the beginning of the 2nd century BC. In this case they present an average weight of around 3.50 grams and this metrology would make them comparable to the Massalian (Marseille) drachma coinage. This weight transformation seems to have begun during the Second Punic War, when Aquitanian and Gallic mercenaries were in the service of both sides in large numbers.

Pomarez coin specimen, 3.35g 12mm CGB auction house

Beyrie-style coin specimen, 3.03gr 16.5mm CGB auction house

These series of coins from southwestern Aquitaine (at least the Pomarez and Beyrie series, since the rare finds in the case of the Greek Y series do not provide much data) were preserved until the middle of the 1st century BC. During the 2nd century BC, the weight of silver was reduced and in the 1st century, they only weighed about 2.80 grams.

Continuing north, between the Atturri and Garonne rivers, we find the series of SOTIATE equestrian coins. In this case, the coins present the image of a horse looking to the left; the horse has a bird-like shape on its back and a decorative symbol on the bottom. They do not show any texture on either the front or the back. On the front, they represent a dislocated female head looking to the left, represented by a comma superimposed on top of the other.

Horseback riding coin sold by CGB auction house – One of the first issues, 4.4 grams, 18mm

Sotiates equestrian coin sold by CGB auction house – one of the 2nd century BC issues 3.42 grams, 19mm

Horseback riding coin sold by CGB auction house – One of the last issues 2.84 grams, 17mm

These equestrian specimens of the Sotiates are classified by experts into four different series. The most important evolution and development would be that of the female figure in the foreground. After the schematic images of the first series, the third series shows closer realism, before falling back into abstraction in the fourth series.

In terms of imagery, these coins are thought to have followed the imagery of the Greek drachmas of Emporion. In the case of the Emporion drachmas, the coins bore the image of the winged horse Pegasus on the reverse and the nymph Arethusa on the obverse.

Silver drachma coin minted by the city of Emporion; between 241-218 BC; 4.63gr 18-20mm

The series of Sotiate horse coins followed the same metrological development as the southwestern coins. The heaviest coins, around 4.7 and 4.3 grams, are thought to date from before the Second Punic War. Later, lighter coins, with an average weight of around 3.5 grams, are thought to have begun to be produced during this war. Finally, by the beginning of the 1st century, the average weight of the coins had again decreased, until coins with an average weight of 2.8 grams appeared.

Historically and in auction sale files, these coins are usually listed under the name of the ELUSATES ethnic group. However, according to the latest opinion of researchers, these coins should be placed under the name of the Sotiates and would be the forerunners of a fifth series.

It is worth remembering that the Aquitaine region was a region free from the Roman Republic until Publius Licinius Crassus subdued the leader of the Sotiates, Adietuanus, in 56 BC. Adietuanus had the support of warriors from the other side of the Pyrenees. This support was probably paid for with coins like this one, since these coins are precisely what make up this fifth series:

Coin showing the reign of the leader Adietuanus, the reverse shows the Roman wolf instead of the horse of the Sotiates. 2.02gr 15mm billon. The following can be seen on the Latin inscriptions (first half of the 1st century BC):

Front: (REX) ADIETVANVS (FE)

Back: SOTIOTA

The coins of Adietuanus already show a clear Roman influence. Although they retain the abstract image of a woman on the obverse, the horse on the reverse has been replaced by a ostrich. In addition, the pictorial texts were written in Latin. These coins of the fifth series are thought to be based on the denarii of the Roman coiner Publius Satrienus.

Denarius coin commissioned by the Roman coiner Pvblivs Satrienvs in 77 BC – 3.82gr

Continuing north to the Garonne River, we find the cross series. These present a series of figures around the cross and flowers but, like the previous ones, do not include any texture. The Garonne River was the border between the Aquitanians and the Celtic Gauls, the river being already under Celtic control. In terms of metrology, these specimens have a maximum weight of 3.6 grams and we can say that they were made from the beginning of the 2nd century BC.

We will not discuss the fascinating specimens, especially those from the Cubist series, in this blog, as they are classified within the existing Gallo-Celtic coinage.

Cross coin specimen sold by CGB auction house, triple flower fringe series – 3.63 grams, 14mm

Cross coin specimen sold by CGB auction house, Cubist series – 2.78 grams, 14.5 mm

As a summary, expert Eneko Hiriart has prepared the following map, indicating the average location of the mintage of each type of coin:

Summary of the location and classification of Aquitaine coin issues prepared by expert Eneko Hiriart

On February 17, 2021, the same Eneko Hiriart gave a talk on this topic at the Koldo Mitxelena Cultural Center. I was very pleased to have had the opportunity to see this talk on ancient coinage among Eneko's sweet northern Basque remains. Here we have the opportunity to enjoy this talk. Congratulations!

Bibliography:

VASCÓNICO-AQUITANO – Language, Writing, Epigraphy – Joaquín Gorrochategui – 2020 – Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza

Aquitano and Vasconico – Joaquín Gorrochategui – 2020 – link

Catalog general de la moneda de Navarre – Ricardo Ros Arrogante – 2013 – Altaffaylla publishing house

Les monnaies des peuples aquitains – Laurent Callegarin – 2009 – link

Production and monetary circulation in the south-west of Gaul in the Iron Age (III and -I BC) – Laurent Callegarin, Vincent Geneviève, Eneko Hiriart – 2018 – link

The cultural singularity of the Western Pyrenees area: dynamics and persistence between the Iron Age and the Roman Era – Eneko Hiriart, Laurent Callegarin, Philippe Gardes and François Réchin – 2018 – link

La moneda aquitana - Imago Pyrenees blog - 2012 - link

Coin of the Basque Country – Pablo María Beitia Arejolaleiba – 2018

ANCIENT BASQUE IN NAVARRE – NAVARRORUM EXHIBITION, Lecture – Joakin Gorrotxategi – link

All personal data collected on this blog will only be used to disseminate the contents of this blog. Personal data will never be transferred or sold to third parties. You can unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the link in the footer of our emails.

Pingback: Ancient Aquitanian Coinage • ZUZEU

Pingback: Searching for the First Traces of Basque…in Coins | History of Basque Coinage