Olite, May 31, 1264,

In Dei nomine Sepan todos aquellos qui esta present carta veran et oyran [que nos] Thibalt, by the grace of God, king of Nauarra, de Campaynna et de Bria, conte palazin seeing and knowing and hearing [good] advice that it is our right to abate the moneda et que seria grant nuestra pro, et nos por piedat eyemos que grant lost seria todo nuestro pueblo de nuestro regno de Nauarra, et por ossar so maynna perdida como es ytar de moneda, todo el The conceyllo de Olit an fecho esta auinença [et compra] de moneda con nos el deuandito rey, assi que nos an feyto tal seruicio por [tanto?] de que nos tenemes bien por gados.

At the Numismata coin fair in Munich held a few weeks ago, I had a surprise. I had no hope of finding any Basque coins, but there were some and I ended up returning home with a beautiful coin from Tibalt I, King of Navarre.

Navarrese silver coin minted in the name of Tybalt I (1234-1253), King of Navarre (also Tybalt IV (1201-1253), Count of Champagne and Brie).

Found: + THEOBALD REX (Wide-legged cross)

Reverse: FROM NAVARIE (The castle of Provins and below it the Crescent and Star of the coins of Sancho VII the Strong)

I have been reading about these coins for a long time, and after acquiring this copy I decided to write the following entry. The basis of this entry has been the works of Miguel Ibañez Artica, Juan Carrasco and especially Ma Raquel Garcia Arancon “Teobaldo II de Navarra 1253-1270, Gobierno de la Monarquia y Recursos Financieros”. But as the main focus, we will take the letter sent by Tibalt II to the city of Orriberri on May 31, 1264. In this letter, the aforementioned king guarantees that he received the payment for the contribution requested from the city of Orriberri in the form of a coinage tax. Coinage was supposedly the right of the king, which gave him huge profits, but at the same time could have brought great losses to his citizens. To avoid this, the king demanded this tax; but why this request and what was this coinage tax in those times?

Tybalt I, Count of Champagne and Brie, one of the most important feudal lords in the Kingdom of France, was the nephew of King Sancho VII of Navarre and became his heir when Sancho died childless in 1234.

Navarrese silver coin minted under the name of Sancho VII (1194-1234), King of Navarre – 0.76 gr

Found: :SANCIVS REX (Image of Antso's face)

Reverse: NAVARRORMV (Hollow moon and six-sided star)

SOLER Y LLACH NUMISMATIC AUCTION 1115 Lot 386 15.10.2020

The Champagne region was one of the most developed regions of Western Europe at that time, thanks to the famous Champagne fairs held in four cities of the region (including Provins and Troyes). These fairs allowed for the exchange of products from northern Europe, especially Flanders and France, and from southern Europe, especially Provence and Italy. As a point of reference, we can say that around the 1260s, while the taxes and fines collected from his Navarrese territories provided Tybalt II, King of Navarre with an annual income of 150,000 sous, the Champagne territories generated financial contributions of about 600,000 sous. This means that the size of the Champagne economy was four times that of Navarre.

Location of the Champagne territories within the Kingdom of France at the end of the 12th century – Wikipedia Commons

The House of Champagne had a long tradition of coinage, but the models of both Tybalt III and Tybalt IV, the two Tybalt counts, became direct predecessors of the coins that would later be minted in Navarre:

Silver coin from Provins minted in the name of Tybalt III (1197-1201) (father of Tybalt I, King of Navarre) Champagne and Count of Brie – 1.03 gr, 20mm

Found: + TEBALT COMES (A broad cross, with the omega ray in its third quarter, the besant ray in the first and fourth, and the alpha ray in the second)

Reverse: CASTRI PROVINCES (A lion between two besants. The coin has obvious symbolism; in its field, which is CHAMP in French, it shows a comb, which is PEIGNE in French)

FROM SOLIDUS NUMISMAT, AUCTION 80, LOT 1538 01.06.2021

Silver coin from Provins minted in the name of Tibalt IV (1201-1253) (King of Navarre from 1234) Champagne and Count of Brie – 1.00 gr, 19mm

Found: + TIBAT COMES (A wide-legged cross, with the omega ray in its first quarter, the moon in the second and third, and the alpha ray in the fourth)

Reverse: CASTRI PROVINCES (Castle of Provins. The coin has a clear symbolism, in its field, which is CHAMP in French, it shows a comb, which is PEIGNE in French)

ANCIENT AND MEDIEVAL COINS CANADA, AUCTION 2, LOS 328 09.11.2019

The arrival of the Champagne Counts, who were the promoters and promoters of these Champagne fairs, brought a great renewal and renewal to the crown of Navarre. King Tybalt I himself had been at the head of the county for just over thirty years when he became King of Navarre.

The new forms of government, the encounter and negotiation with the old local customs, the pressures and conflicts were numerous. The reflection of all these discussions was the fact that the old Charter of Navarre was put into writing in 1238.

If we look at the structure of the coinage system, the monetary system of these times in Western Europe was based on the so-called pennies and half-pennies (or meaila, meaja or obolo) established since the Carolingian period. The coins were small (between 18 and 20 mm in diameter), weighed around one gram and, depending on the reign of these times, had a silver content of over 250 thousandths to 333 thousandths. In the case of the coins, in theory they had to have the same silver law but half the weight of the pennies, and sometimes they had variations of the silver law. After the large amount of money minted in the time of Sancho VII, the money of the Kingdom of Navarre was known simply as diri sanxete or sanxete.

Navarrese silver coin minted in the name of Tibalt I (1234-1253), King of Navarre (also Tibalt IV (1201-1253), Count of Champagne and Brie) – 0.94 gr

Found: + THEOBALD REX (Cross with a wide lance, the sting in the fourth quarter) (See the spelling of A izkia)

Reverse: FROM NAVARIE (The castle of Provins and below it the Crescent and Star of the coins of Sancho VII the Strong)

Hervera Auction 86 – Room auction Lot 500 30.04.2015

Navarrese silver obol or coin minted in the name of Tybalt I (1234-1253), King of Navarre (also Tybalt IV (1201-1253), Count of Champagne and Brie) – 0.54 gr, 14mm

Found: + THEOBALD REX (Cross with a wide lance, the sting in the fourth quarter) (See the spelling of A izkia)

Reverse: FROM NAVARIE (The castle of Provins and below it the Crescent and Star of the coins of Sancho VII the Strong)

CNG (Classical NUMISMATIC GROUP) Electronic Auction 531 Lot 1485 25.01.2023

The new Navarrese coins of Tibalt I, abandoned the model with the face of Sancho VII and largely adopted the model of the Champagne coins. On the obverse they featured the Christian cross and on the reverse, the image of the castle of the Champagne city of Provins. However, under the castle, instead of the crest, they show the crescent and star of Sancho VII. Although the image-texts were transformed according to the Navarrese context, we can still see traces of the handwriting of Sancho VII's reign, for example in the case of the letter A. The special feature of these coins is the thorn that can be seen in the fourth quarter of the Christian cross.

Navarrese silver coin minted in the name of Tybalt II (1253-1270), King of Navarre (also Tybalt V (1253-1270), Count of Champagne and Brie) – 0.93 gr

Found: : THEOBALD REX (A wide-legged cross, without a sting in the fourth quarter) Note the spelling of A izkia

Reverse: FROM NAVARIE: (Castle of Provins and below it the Moon of the coins of Sancho VII the Strong, without stars)

Aureo & Calicó – Floor Auction 345 Lot 321 13.02.2020

If we look at the coins of Tybalt II, the son and heir of King Tybalt, we can notice the gradual development of the pattern. Only the moon appears under the castle on these coins, without stars and the cross-shaped spike has also disappeared. As for the script, the letters show the beginnings of Gothic script, as clearly shown by letter A.

As is clear from the Charter of Navarre, the medieval kings minted new coins at the beginning of their reign. After the new coin was minted, a period of forty days began in the kingdom of Navarre, during which the king opened a money exchange board. On these money exchange boards and during the aforementioned forty days, the Navarrese could exchange the money of the old reigns for the new money. These money exchange boards were opened in the most important cities and towns of the kingdom.

Every new coinage exercise brought profits to the royal house. On the one hand, there were the profits from the so-called "senyorage", which reflected the difference between the cost of silver and the value of the coins, and on the other hand, the profits from the commissions given in exchange operations. But for all Navarrese, there was an even more tempting but also more dangerous activity that the king could engage in. This activity was the temptation to reduce the standard or weight of the coins (or both at the same time). By doing this, the royal house could mint more coins with the same nominal value per individual piece, increasing the mass of coins available and obtaining profits in the short term.

In those days, they did not yet have the thick economic books and theories of our day, but they knew very well that such things would lead to an increase in prices (inflation) and the impoverishment of the Navarrese majority. For this reason, during the reign of King Tibalt II (1253), they made him swear an oath to maintain the value of the currency and not to mint new ones for a period of twelve years. But after this period had passed, the royal court declared the custom of demanding a tax called “monedaje”. This tax could be collected only once during the reign of each king. In exchange for the collection of this tax, the royal court undertook to maintain the law and weight of the currency for the rest of the king’s reign (or in some cases, not to mint any more coins).

One of the first cities to pay this “coinage” tax was the city of Olite-Rriberri, when the twelve-year period was about to expire, and King Tibalt II wrote to Rriberri guaranteeing payment on May 31, 1264. Thanks to this letter, for the first time in the history of Navarrese coinage, we have recorded in writing the law and weight of the coins minted during the reign of Tibalt II:

Et nos por [...] que uos el dito conceyllo nos auedado, auemos us signed this coin for all our lives, et que la crescamos et la fagamos de peso de diez et [eight] sueldos el marco et de ley a quatro menos [pegessa fine silver] and that we don't have to do anything and that we don't agree that we should make the currency apart from the peso and the law as it is said in Suso, and that we make it work every time we can earn something [...] and that where we were looking for another career that we would demand money for [de] money, we would pay some money for a nengun omne I a nenguna muller del dito conceyllo in all our life.

As this passage indicates, the legal value of Tybalt II's money was three drachmas and eighteen grains; four drachmas minus a pegessa, that is, four drachmas minus a quarter drachma. If we consider that each coin was worth twenty-four grains,, a quarter of a penny would be six grains. This would be equivalent to today's 312,5 would give us a legitimacy of around one thousandth. As for the weight, each mark of work was said to have yielded 18 sous; if we take into account that each sous contained twelve sous, a simple operation would give us a total of 216 sous. If we take into account that each Mark of Troyes contained 244.75gr, each sous would be 244.75gr/216 grains = 1.1331 gr/piece It would have a nominal weight of .

The same passage suggests that the coinage at the beginning of the reign of Thibault II caused the loss of value of the obols or coins. In this letter, the king promises the people of Riberri not to mint new obols. In fact, if we examine the average weight of the obols of Thibault II, compared with those of his father, we can note that those of his son are considerably lighter.

Navarrese silver obol or coin minted in the name of Tybalt II (1253-1270), King of Navarre (also Tybalt V (1253-1270), Count of Champagne and Brie) – 0.39 gr

Found: : TIOBALD REX (Wide-legged cross)

Reverse: FROM NAVARIE (Castle of Provins and below it the Moon of the coins of Sancho VII the Strong, without stars)

AUREO & CALICÓ SL, AUCTION 375, LOT 407 20.10.2021

The works “Teobaldo II de Navarra 1253-1270, Gobierno de la Monarquia y Recursos Financieros” by Ma Raquel Garcia Arancon and “El impuesto del Monedaje en el Reino de Navarra (CA 1243-1355)” by Juan Carrasco provide us with details of this “coinage” tax collected between 1264 and 1266. It seems that the kingdom of Navarre had a military intervention in the county of Bigorre during 1266. The accounts of the kingdom of that year show that the coinage tax was used to pay for this intervention. But how much money was usually collected and what currency was used for this type of payment in Navarre in the middle of the 13th century?

The amount of money collected was usually enormous, but at the same time, and as we will see, a large part of the money collected was not paid in Navarre's santcheets, but in Tournai money from the French kingdom. In fact, the merchants and francs of the cities and burghs who had relations with foreign countries paid a large amount of tax in French money. Those who had local relations, on the other hand, mainly used santcheets. Let's look at a Tournai coin from these times:

Tournai silver coin minted in the name of Louis IX (1226-1270) King of France – 1.06 gr 18.5mm

Obverse: + LVDOVICVS REX (Wide-legged cross)

Reverse: TVRONVS CIVIS (Image of the castle of Tours)

INUMIS, MAIL BID SALE 9, LOT 404 23.10.2009

The standard of these Tournai coins was slightly smaller than that of Navarre, three drachmas and fourteen grains, which is about 299 thousandths. Each mark of minting produced 217 Tournai coins, resulting in a nominal weight of 1.127 grams for each coin, close to but slightly below the weight of Navarre coins.

As the Navarrese account books show, seven Tournai dinars were exchanged for six sanxetari dinars, reflecting these differences in weight and law. Later, towards the end of the century, in 1291, when the authorities, under the rule of the French monarchy, established the full equivalence between sanxetari and Tournai dinars, public anger arose.

Through the collection of this currency tax 107.826 salary and salary 254.215 The king received a salary and four Tournai coins in the years 1265 and 1266. As can be seen, 2/3 of the collection was collected in Tournai coins and one third in sanxet coins. This tax collection 325.725 He provided the royal court with an income of around 100,000 shillings in these two years, as much as the kingdom had provided him with through ordinary income for two whole years.

In payment of this coinage tax, each family or household had to contribute two morabetinos or morabedias, as stated in the letter sent by the king to the city of Tudela on December 6, 1264. Households with a treasury of less than one hundred morabetinos could pay the tax for two years, one morabetino each year, on the day of the Holy Domes.

3.82 gr gold morabetine minted in the city of Toledo in the name of King Alfonso VIII of Castile (1158-1214)

AUREO & CALICÓ SL, AUCTION 376, LOT 248 17.11.2021

These morabetinos were gold coins minted in the Kingdom of Castile, but in addition to being used as physical coins, they were also used as a unit of account. In many accounts of the kingdom, money and sueldos were converted into morabetinos, where each morabetino was worth 7.5 sueldos or 90 dirhams (8 sueldos or 96 dirhams of Tournai).

As we have seen, in addition to the silver coins minted there, the use of foreign money was very common. Especially in the border territories, foreign coins were used to buy supplies, pay for works or collect taxes from foreigners. Thus, the monastery of Leiria collected taxes from its Aragonese slaves in Aragonese money. In the cities bordering the Castilian territories, the use of Burgos silver coins was common. But what happened in the territories of Lower Navarre?

In Lower Navarre, silver coins from Bearn were used mainly, known as Morlaas coins. The creation of these coins is considered to have occurred at the beginning of the 12th century, but we are not entirely sure until when they were minted. They bear the name of a count named Centullo on the obverse and mention honor, peace and strength on the reverse. In general, they were coins of a higher silver standard and of slightly greater weight. As a reflection of this, six Morlaas coins were exchanged for nine sanxeta coins, which means that the Morlaas coin should have had a silver content of more than the sanxeta.

Silver biarno or bigor coin minted in the name of Count Centulo (12th century)

Obverse: CENTULLO COM (Broad-Legged Cross, two besants in the first and second quarters)

Reverse: ONOR FORCAS PAX (The word PAX on two lines)

AUKTIONSHAUS HD RAUCH GMBH, AUCTION 114, LOT 549 16.06.2022

Let's see how the king's letter to Olite-Erriberri ends:

And this purchase and auinença that the said council made with us, that ualga in all our life and no more, and there was a king that uiniere empues us that where I could demand this by customne. And because this authority and purchase of the coin is firm and valid, we, the soveredito king don Thibalt, have sworn by the Holy Cross and by the Holy Gospels, that we will maintain it as it is said to be in all the time of our days .

And in testimony of all this, we give our letter open, sealed with our seal pendient to our beloved council of Olit, which letter was made and given in Tudela, the Saturday after the day of May.

The king sent her. Written by Miguel Periz, anno Domini Mº CCº LXº quarto.

The king vows not to repeat the coinage tax on the holy crosses and gospels during his reign; he also expresses his intention not to make it a custom for future kings. Tybalt II's early death on his return from the crusade enabled him to fulfill the first purpose; the second was a different matter, and subsequent kings generously put their hands into the pockets of their subjects.

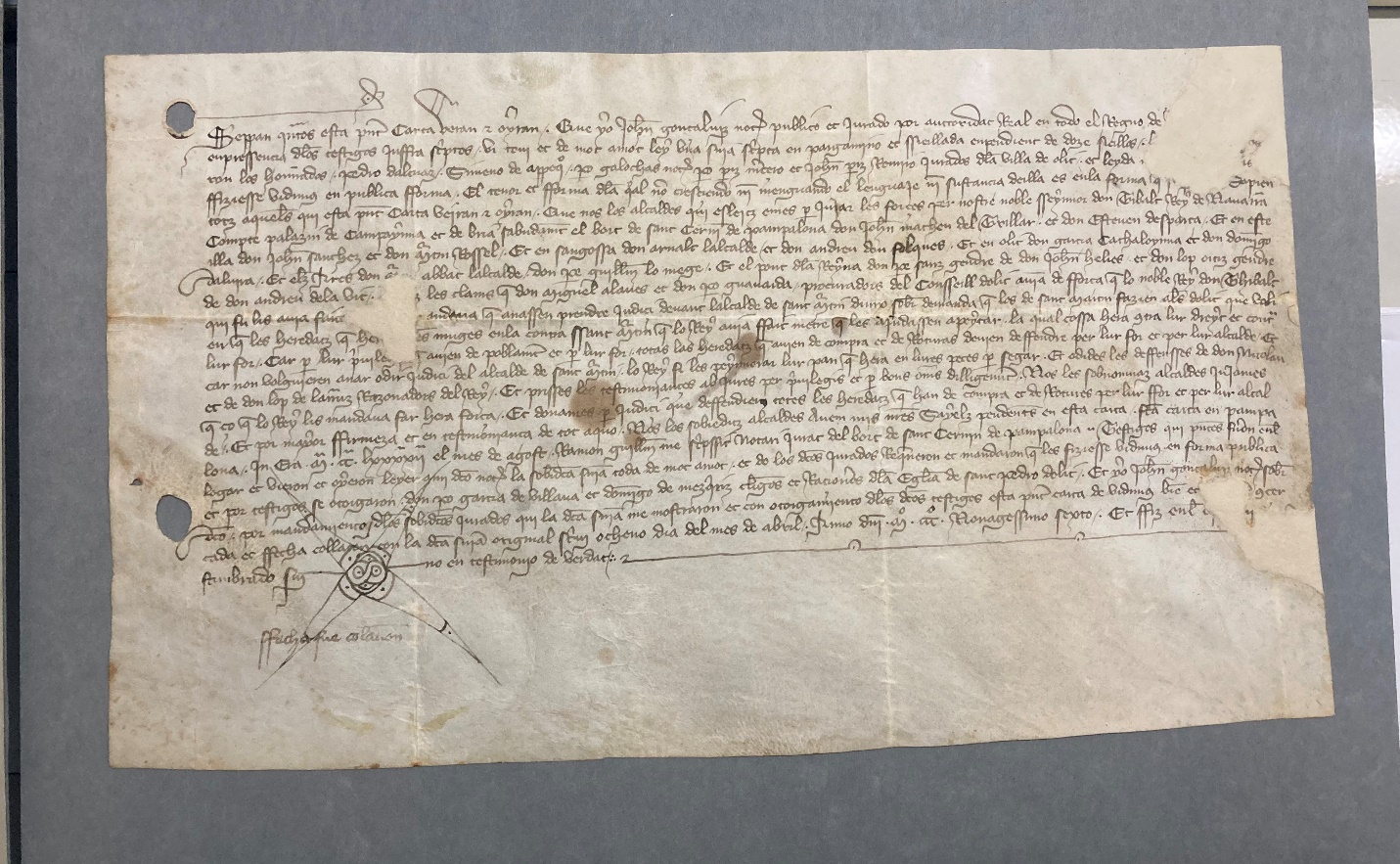

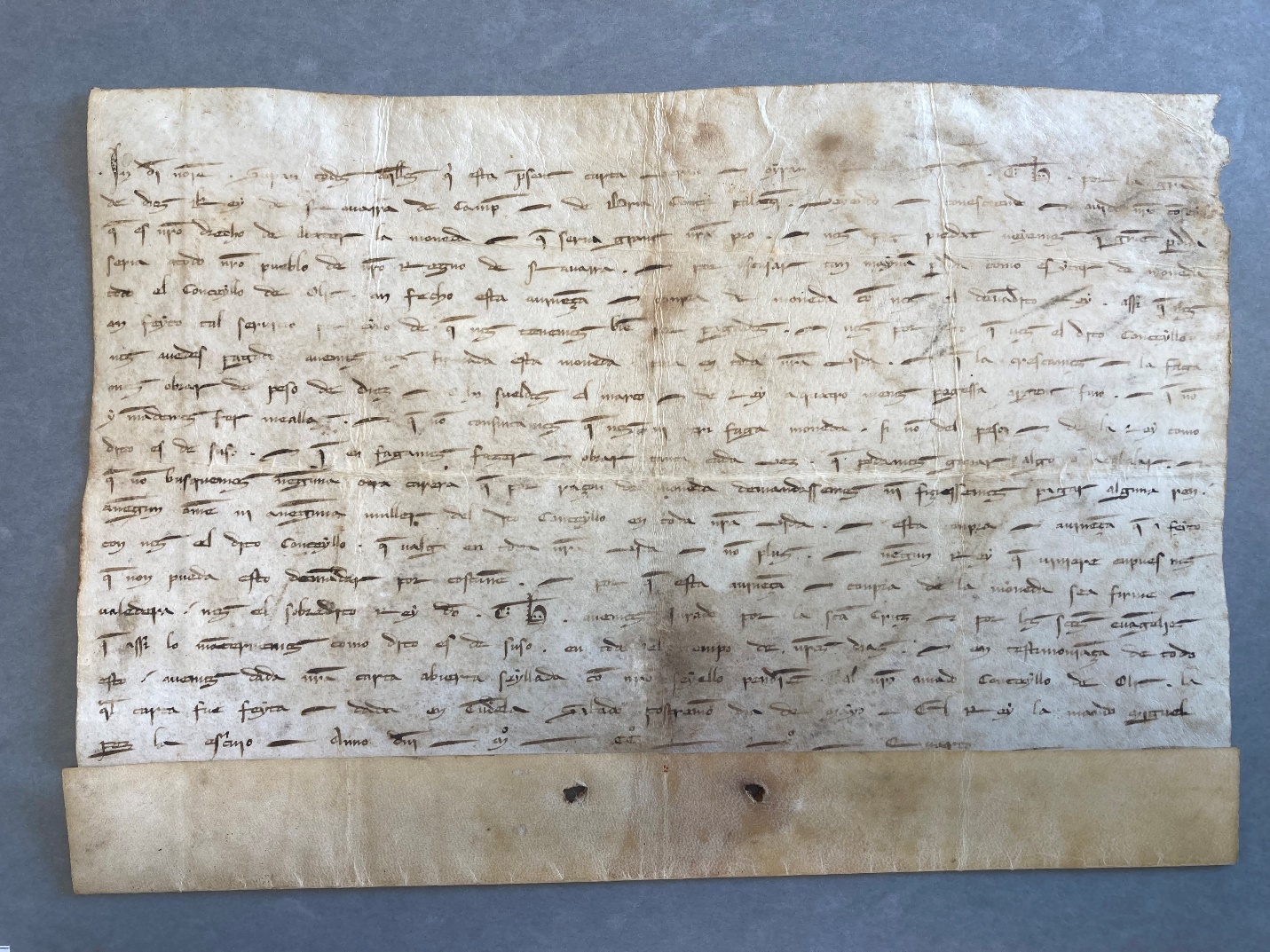

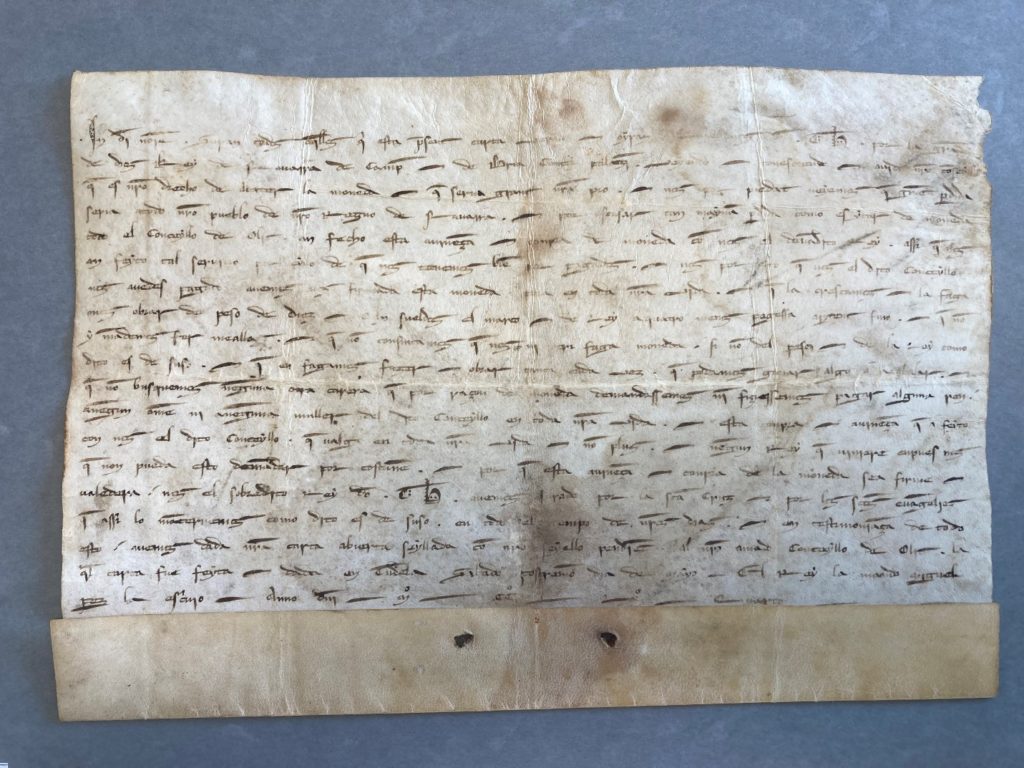

A final note before concluding. While I was preparing this entry, I requested a photo of the aforementioned document from the municipal archive of Olite-Erriberri. I directed my request to document 12 in the municipal archive, which is the document number corresponding to this letter that Miguel Ibañez Artica and Ma Raquel Garcia Arancon believe to be mentioned in their books and in the diplomatic collection of Tibalt II. Miguel includes a photo of document 12 in his book and when I received a copy of my photo, I thought I was on the right track, since the two were the same.

Photo of document 12 from the Olite-Erriberri municipal archive – Courtesy of the Olite-Erriberri municipal archive

But when I started reading document 12 through the photo I received, I noticed that the sentences I read did not match what I expected. I had requested and received the wrong document, but then, where and what is the correct document? I decided to go to the Royal General Archive of Navarre and there, professor and archive technician Peio Monteano explained to me that the document I was looking for was document 7 of the municipal archive of Olite-Erriberri. Thanks to Peio for these simple pages.

I went back to the town hall of Orribberri, and once again, with great courtesy, the municipal archives sent me a photo of the requested document 7. My heart was pounding when I enlarged the photo and started reading; this time, I was on the correct document.

For everyone, here is the letter from Tudela to the people of Olite, written by King Tibalt II on May 31, 1264; greetings!

Photo of Document 7 from the Olite-Erriberri municipal archive – Courtesy of the Olite-Erriberri City Council

Restoration work carried out in recent years has allowed for easier understanding of some words.

Bibliography:

Navarre medieval currency – Manual of Numismatics – Miguel IbaÑEZ ARTICA – 2021

Navarre under the French influence of the dynasty of Champagne – Miguel IbaÑEZ ARTICA – 2013 – link

A war between currencies: the "sanchete" of Navarre against the "tornés" of France - Miguel IbaÑEZ ARTICA - 2006 - link

Typology of the coins of Sancho VI and Teobaldo I, kings of Navarre – Miguel IbaÑEZ ARTICA – 1998 – link

Metallographic study of medieval coins: Reino de Pamplona-Navarra, centuries XI-XIII – Miguel IbaÑEZ ARTICA – 1998 – link

Les conditions du denier parisis et du denier tournois sous les premiers Capétiens – A. Dieudonné – 1920 – link

Les Monnaies françaises royales, Tome I, Hugues Capet à Louis XII -JEAN DUPLESSY – 1999

TEOBALDO II OF NAVARRA (1253-1270), GOVERNMENT OF THE MONARCHY AND FINANCIAL RESOURCES – M. RAQUEL GARCIA ARANCON – 1985

DIPLOMATIC COLLECTION OF THE KINGS OF NAVARRE OF THE CHAMPAGNE DYNASTY. TEOBALDO II (1253-1270) – M. RAQUEL GARCIA ARANCON – 1985 – link

REGISTERS OF TEOBALDO II 1259, 1266 – Juan Carrasco – 1999 – link

The coin tax in the kingdom of Navarre (ca. 1243-1355) – Juan Carrasco – 2011 – link

Money and Meajas de frontera made in the name of Count Céntulo in the XI-XII centuries – Manuel Mozo Monroy – 2020 – link

Monnaies féodales de France – VOL3 – Faustin Poey d'Avant – 1860 – link

Monnaies Féodales Françaises – Emile Caron – 1882 – link

Coin of the Basque Country – Pablo María Beitia Arejolaleiba – 2018

The County of Champagne (950-1316): a very short introduction– SCHWERPUNKT – Youtube video – link

Rise and Fall of the Champagne Fairs – SCHWERPUNKT – Youtube video – link

All personal data collected on this blog will only be used to disseminate the contents of this blog. Personal data will never be transferred or sold to third parties. You can unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the link in the footer of our emails.

Pingback: Tybalt of Champagne's Coinage Tax • RIGHT

Pingback: Paulo Girardi and his Navarrese Currency Report | History of Basque Coinage

Pingback: The Structure of the Biarritz Coins of the Time of Queen Catherine | History of Basque Coinage