At the end of the 1640s, a huge scandal spread throughout the Spanish kingdoms and, to a large extent, throughout Europe. The 8 and 4 reales coins brought annually by the Indies fleet from the territories of Peru did not meet the required silver weights and laws.

The reales had a legal value of around 931 thousandths of silver at the time (11 dinars and 4 granos) and, by law, were supposed to weigh 3.43 grams per real. Instead, the coins minted at the Potosí mint were worth 25% silver.

8 reales coin minted in Potosi in 1647 (P Izkia) – 21 gr and 81% silver content according to X-ray analysis – Z Izkia represents the assayer Pedro Zambrano, caught in the commotion

Merchants refused to accept Peruvian coins in exchange for their services and goods, and soldiers were on the verge of mutiny, risking their lives only for good silver. The reputation of the kingdom was steadily deteriorating, compounded by the monetary crises of recent years, which this time also brought scandal.

If you want to imagine what happened, imagine what would happen today if a third of the 50 and 20 euro banknotes we have in our pockets suddenly received a new value of 40 and 15 euros... and all this loss was on top of that!

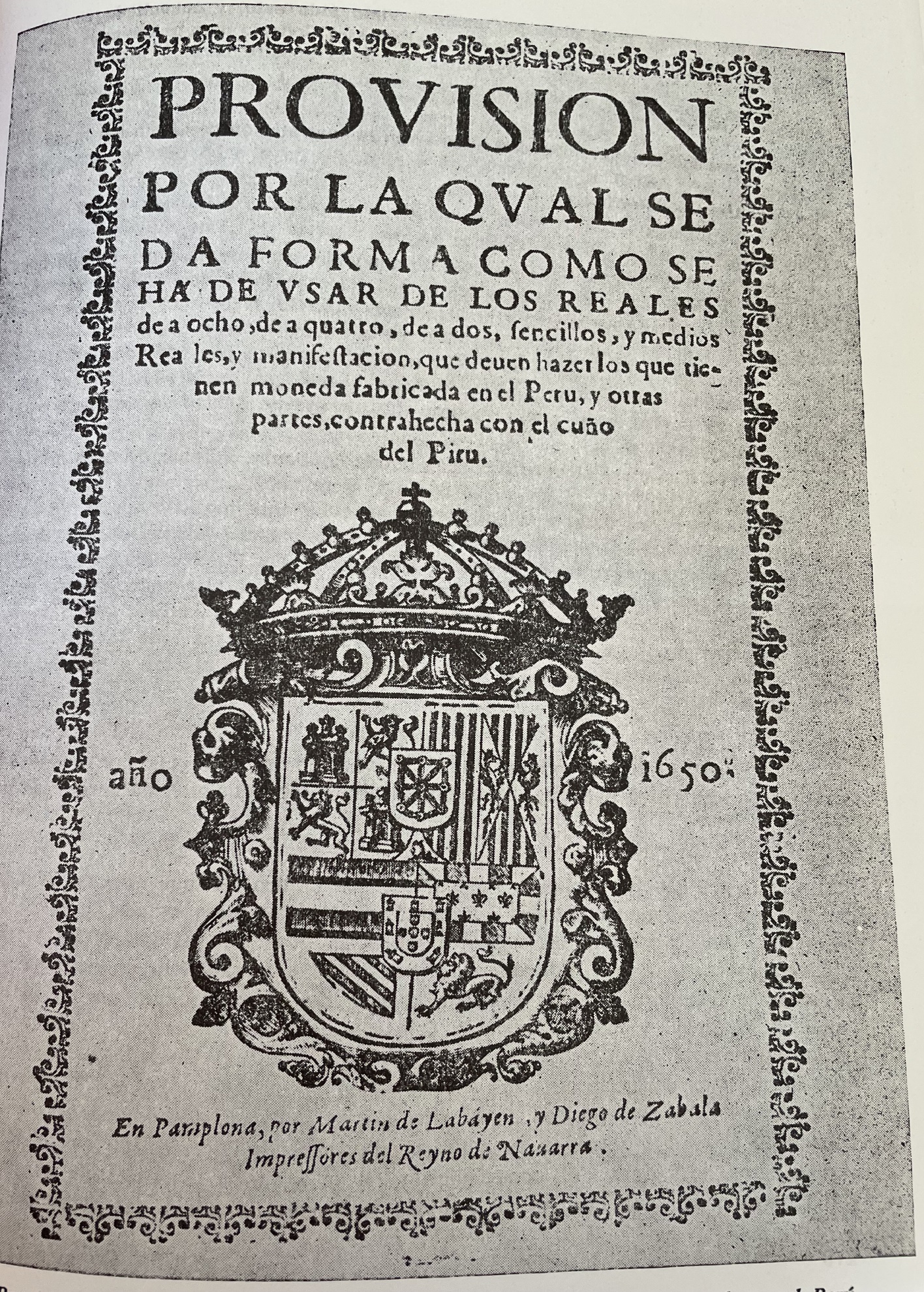

In fact, the royal council decided on the only possible way out. An order was issued to collect and withdraw the coins brought from Peru in all the kingdoms of the Spanish monarchy. The kingdom of Navarre was no exception, as the decrees published in Pamplona on October 29 and November 24, 1650, clarified the procedure to be followed.

The book “La moneda navarra y su documentación: 1513-1838”, published in 1975 by the writer Jorge Marín de la Salud, provides details of the order issued on October 29, 1650.

Cover of the royal decree published in Pamplona on October 29, 1650

In summary, we can say that the royal decree required the silver coins minted in the Peruvian mint (that is, the mint of Potosi) to be brought before experts. If the experts declared the coins to be legitimate, they would be returned to their owners, but if not, the authorities would lock them up. After recording the number of coins and their owners, the boxes containing the coins were to be taken to Pamplona, where the experts of the mint would determine the compensation to be paid. At the same time, it required the acceptance of coins minted in the Mexican and Castilian mints in daily transactions. Within ten days, the population was required to report the Peruvian coins they owned, otherwise they risked losing their coinage at the expense of the informers.

As might be expected, the royal decrees of 1650 brought only confusion and distrust. If we today distrust state institutions, imagine what kind of proposals they made in those days…give me the coins I had forged myself and I will pay off your debts one day, after I have decided the exchange rate to be given! Oh, and on top of that, the costs of transporting the coins to Pamplona are yours, the owner of the coin!

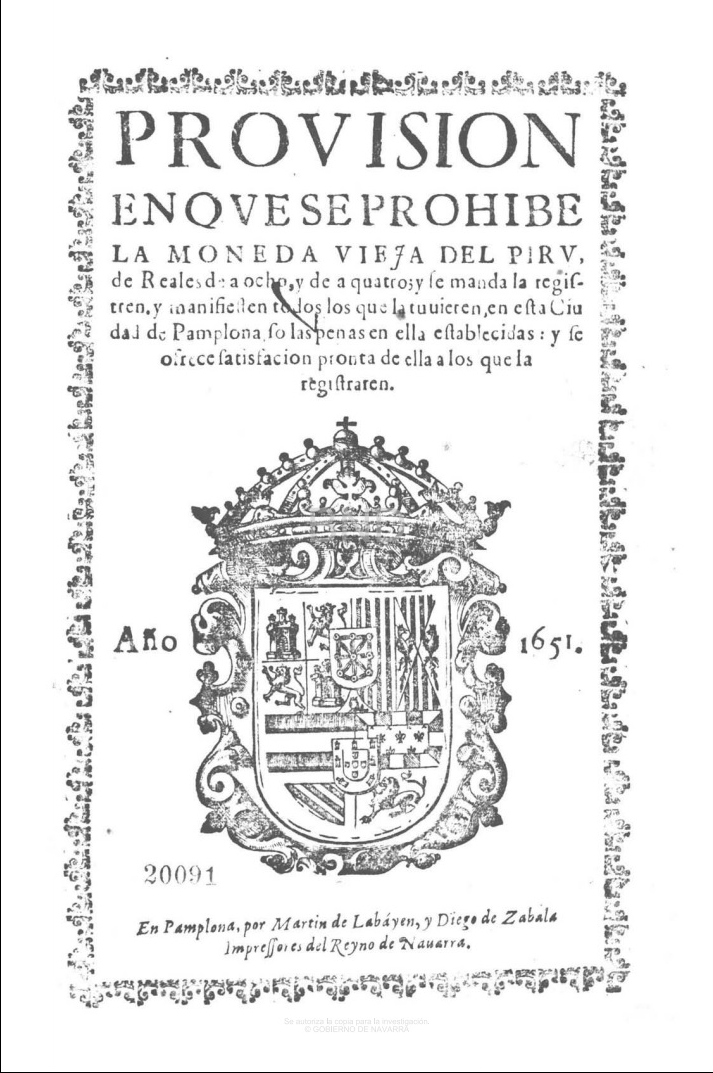

On the first of March of the year 1651, they had to publish another provision or new royal decree. This royal decree is available to read in the digital library of Navarre and I highly recommend it to anyone (all the details in the bibliography, but here is the link: Binadi – link)

Cover of the last royal decree on the coins of Peru, published in Pamplona on March 1, 1651

The order of the first of March first summarizes the complicated situation, since it was ultimately impossible or very difficult to distinguish legitimate coins from counterfeit ones, and as a result, trade was in complete decline. Mistrust and uncertainty are not suitable companions for trade.

Ondorioz, errege probisio berriak, on edo txar, Peru-ko lurraldeetan landutako zortzi eta lau errealetako txanpon zahar guztien bilketa agindu zuen. Zortzi errealetako txanponen truke, 6,75 erreal jaso beharrean ziren jabeak, Mexiko eta Gaztelako txanponetxeetako edo Iruña bertako txanponetxean landu beharreko erreal txanpon berritan. Lau errealeko txanponen truke, 3,375 erreal berri jasotzekotan ziren. Orohar neurri honek, Peruko txanponen jabeei %16 inguruko galerak eragozten zizkien.

Anyone could request that their coins be set aside and classified separately. These coins were demanded separately, and the silver obtained was transformed into new coins minted legally, after deducting expenses and taxes.

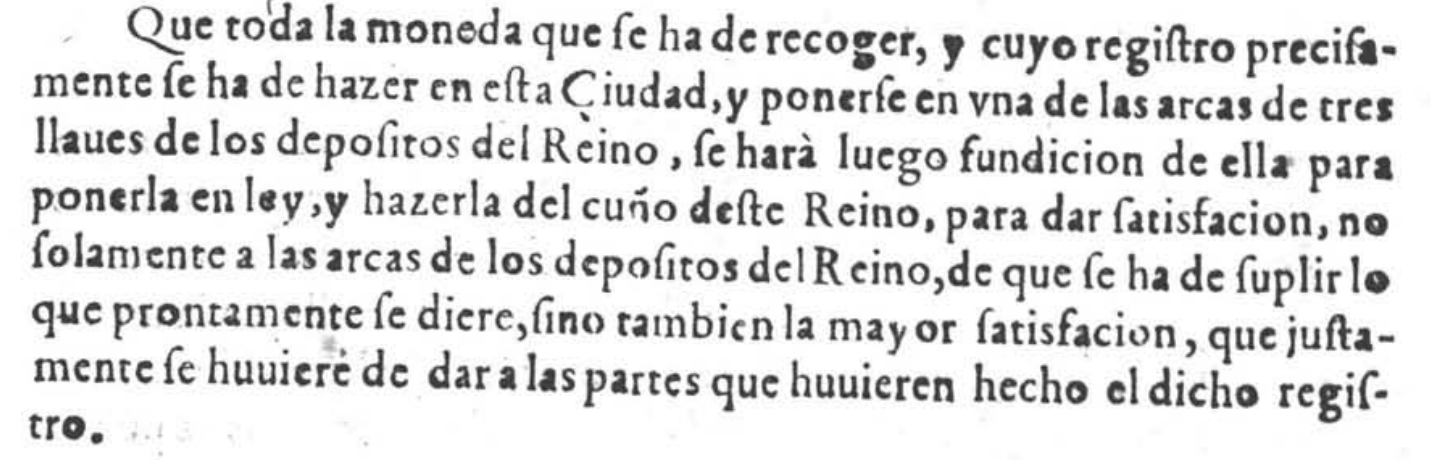

This document, dated March 1st, finally guarantees the origin of the silver coins minted at the Pamplona mint in 1651 and 1652:

Extract from the decree on the coins of Peru, published in Pamplona on March 1, 1651

In fact, after having not minted any silver coins for about forty years, the Pamplona mint once again minted half real, one real, two real, four real and eight real coins. We do not know how many were minted, as no records have been kept, but today they are only found in the hands of a few collectors and are sold at auctions every year.

The only known example of 8 reales from 1651 – 27.34gr – 37mm – National Archaeological Museum of Madrid

Found: PHILIPVS.D.GRACIA REX P VIII

Hell: CASTELLE.ET.NAVARRE 1651

The only known example of a 4 real coin from 1651 – 13.49gr – Jesus Vico auction house 2013. November 7 – €5000 –

Front: PHILIPVS.DG REX P IIII

Back: CASTEL.ET.NAVARE 1651

In early 2024, this unique and unique 4 real coin from 1652 appeared in northern France. This coin bears a re-stamp of the Golden Fleece minted in Flanders between 1652 and 1672.

The only known example of a 4 real coin from 1652 discovered in northern France in early 2024 – 13.26gr 29mm diameter – Photo courtesy of Eric Thobois

Front: PHILIPVS.DG REX P IIII

Back: CASTELLE.ET.NAVAR 1652

Re-stamp of the Golden Fleece, minted in Flanders between 1652 and 1672

One of the famous 2 reales coins from 1651 – 6.25gr – Tauler&Fau auction house 2021. June 8 – €5000 –

Obverse: PHILIPVS.DG REX P II

Back: CASTELE.ET.NAVARE 1651

One of the most famous examples of a real from 1651 – 3.39gr – Tauler&Fau auction house 2021. June 8 – €2000 –

Obverse: PHILIPVS.DG REX PI

Back: CASTELE.ET.NAVARE 1651

One of the most famous half real coins from 1652 – 1.55gr – Tauler&Fau auction house 2021. June 8 – €1800 –

Front: PHILIPVS.DE.GRACI PA

Back: CASTE.ET.NAVA 1652

Only one example of eight reales is known, but more were minted, as shown by the dies kept in the Museum of Navarre.

One of the dies on the back of the 8 reales coins kept in the Museum of Navarre

Height = 39 mm; Width = 43 mm; Diameter = 40 mm; Weight = 424.30 gr

+CASTELLE(Flower)ET(Flower)NAVARRE(Flower) 1651

As can be seen, the dies were beautifully crafted, but the same cannot be said for the silver coin dies. The coin dies or cospelas were made too thick, so the edges were trimmed and trimmed with scissors until the correct weight was achieved, making it almost impossible to read the entire image text. The pieces were used for a long time and most of the ones that have come down to us show considerable wear; unfortunately, between the cuts and wear, the fine art of the coins cannot be fully analyzed by looking at the pieces alone.

The number of reverse dies preserved in the Museum of Navarre is as follows, classified by the year in which they were presented (unfortunately, no obverse dies are preserved):

| Number of dies kept in the Museum of Navarre | ||||||

| 8 Real | 4 Real | 2 Real | A Real | Half Real | Total | |

| 1651 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 5 | – | 20 |

| 1652 | – | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| 1653 | 1 | – | – | – | – | 1 |

As can be seen, the largest number of dies corresponds to the year 1651 and we can conclude that the largest number of coins were minted in this year. A single die from 1653 is preserved, for 8 reales. This die shows clear traces of its use and therefore we can suspect that at least 8 reales were minted in 1653. In this case too, we do not know of any die from that year today.

The only 8 reales die from 1653 preserved by the Museum of Navarre

Height = 49 mm; Width = 40 mm; Diameter = 37 mm; Weight = 488.40 gr

It is very likely that only a portion of the dies used have reached our hands, but we can estimate that in total at least 300,000 coins were minted (using the approximation that each die was used to mint at least 12,000 pieces).

In fact, when this entire amount of coins was minted, the courts of Navarre complained to the king. For a long time, according to the request presented and accepted by the courts of Sangüeza in 1561, coins minted in the kingdom of Navarre had to present the simple title of the kings of Navarre and the ordinal that corresponded to them as kings. Therefore, the image text CASTELLE ET NAVARRE on the dies of 1651, 1652 and 1653 was contrary to ancient charters and customs.

Here is the complaint of the courts from 1652 (in the original Spanish):

The coin of silver that is made is only carried by the edge; "Philippus, Dei gratia Navarrae Rex".

Pamplona Year of 1652. Law 51.

In the silver coin that has been made lately by the maestro mayor and treasurer of the House and Seca of this kingdom, this title and inscription has been put on the edge: Philippus Dei gratia Castellae & de Navarrae Rex, year 1651, 1652, 1653, and this is not in accordance with what is provided by Law 2, second book of the Cortes of the year 1576, which is Law 5 of lib. 5, tit. 6 of the Compilation of our trustees. As a remedy for the grievance, it was requested that no new developments be made due to the provision it contains, which is Law 46 of the Cortes de Sangüessa of the year 1561, which is the 2 of the same title of the Compilation; and for her it was ordered that the sign of the arms section should say: Philippus Dei gratia Navarrae Rex, and this was repaired by Law 5. And supposing that the said new coin of silver is coined contrary to the provisions of it and in said Law 2, we beg your Majesty to order that from here on the currency of this kingdom cannot be coined de plata que se con el trerero de la que ha se ha barrado; and that the one having done it as it is with the sign that it has, does not seem to be detrimental to the said laws, and it is brought in consequence; y que la que se brarare aquí adelante haya llevar por trerero: Philippus Sextus Dei, gratia Navarrae Rex, that in it, etc.

Decree.

To this we respond that se haga como el reino lo pide.

This petition refers to a counter-forum reported in Pamplona in 1576. In this case, the Gonzaga viceroy describes an appeal against a decision made during the reign of King Philip II of Spain. Viceroy Gonzaga ordered the minting of coins that presented Philip as King of Spain and Navarre, and used the second corresponding to Castile in the king's ordinal. The courts reminded the king that on the coins of Navarre King of Navarre that it should appear only without any mention of the kingdom of Spain and that the ordinal of his kingdom of Navarre was the fourth instead of the second.

This appeal clearly illustrates the argument used again by the courts in 1652:

Pamplona Year of 1576. Law 2. Notebook 2.

By Law 46 made in the Cortes of Sangüessa in the year 1561, it was ordered to beat the coin of fleece, strips of a diez and six cornados, and half strips with a cross and a sign; in the other with the arms of Navarre, as in the said Ley parece. And not only has the content in it not been fulfilled, but before there had been a new thing not used in this kingdom by the said Vespassiano Gonzaga, Visso-rey, he ordered to change the sign that said before: Philippus Dei gratia Rex of Navarre, tell me: Philipus Secundus Hispaniarum, & Navarrae Rex. Lo qual is against the laws and customs and royal oath of Your Majesty. Because in this kingdom never in the coin that has been merged by Your Majesty and by the emperor and the catholic king his father and grandfather, and the other kings that have been there in this kingdom, have been put there but kings of Navarre, and not of Spain ; because that makes her like only king of Navarra, and in respect of her neither can you say: Philip II, but Quartus;

y si a eto se diese lugar, demás que sería daño del reino, es también agravio de él, por ser contra sus Fueros, Leyes y customumradas juradas. We beseech your Majesty to order that there be no novelty in the reason of the said provision against the said laws and customs of this kingdom; y se guarda de la dicha Ley de Sangüessa in el batir de las tarjas, y medias tarjas, arms, y letras de ellas.

Decree.

To which we respond that as much as the coin is to be mixed, it is done in the order and form that the kingdom asks for it.

It is not certain that the complaints of the courts in 1652 prevented the minting of the eight-real coins bearing the year 1653, at least the traces of the use of the preserved die do not give reason to suspect this. However, the image texts requested by the courts appeared on the largest silver coins ever minted at the Pamplona mint, the fifty-real pieces.

These fifty real coins, known as “cincuentín”, were minted between 1609 and 1682. The minting of the fifty reals was carried out at the Segovia mint, whose workshop, consisting of rolling and engraving rollers powered by a watermill, was unique in the entire kingdom, the only one that allowed the minting of these coins, which were 73mm in diameter and weighed around 170 grams of silver.

Traditionally, the fiftieths have been considered commemorative and prestigious coins, as these special issues were struck to mark important events in the monarchy. They were also used as a means of attracting the silver arriving in Seville to the Segovia mill mint, which was the only privileged “industrial” mint of the crown that could strike fiftieths. As a result, many merchants received special minting licenses, interested in keeping their silver at this high value, and it seems that they came into circulation on the streets, although in very small quantities.

Fifty-year 1651 coin, made by rolling and engraving rollers driven by watermills at the Segovia mint – 174.2 gr

Obverse: PHILIPPVS IIII DG 50 I (I (Hipólito de Santo Domingo the Enthroner)

Reverse: HISPANIARVM REX 1651

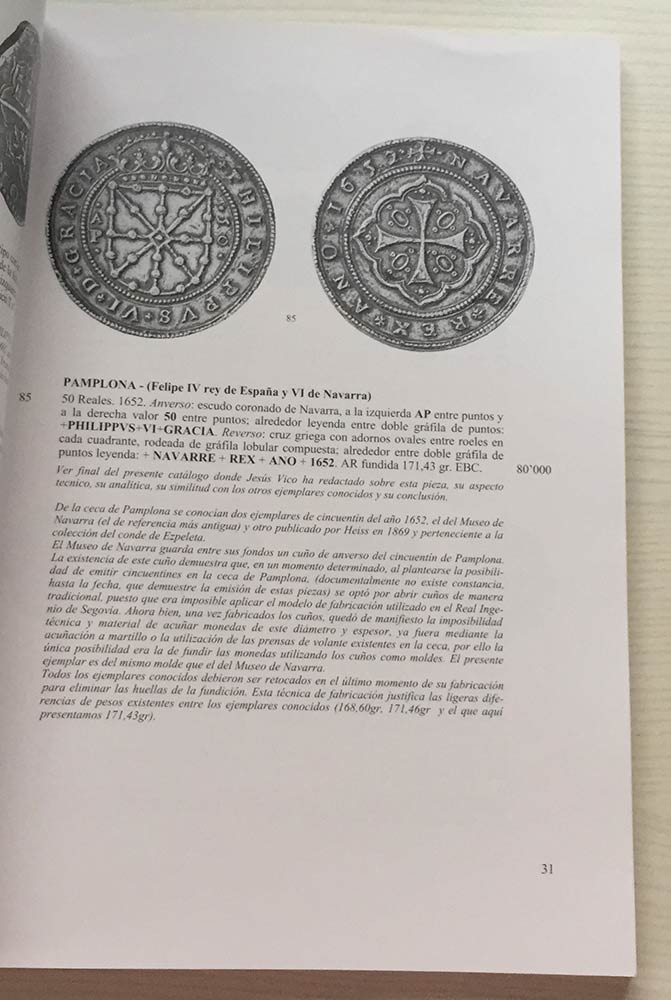

However, the fifty pieces were not only minted in Segovia. The fifty pieces, which bear the year 1652, were minted in an unknown quantity at the Pamplona mint. Thus, the largest silver coins minted in a Basque mint were created. And of the unknown number produced, only four pieces are said to have survived to our days. However, I have not been able to guarantee the reference of these four possible pieces. Two pieces can be absolutely guaranteed, if we look at the Navarrese museum and the auctions that have taken place in the last forty years. According to the information provided by the auction houses, a third piece, which is in the hands of a private collector, can also be guaranteed. I have not been able to find a reference to the fourth piece. Here is an overview of the history of the pieces that have been found.

The first is exhibited by the Museum of Navarre with the following characteristics:

Victory: Philip VI. King of Navarre, Philip IV. King of Spain

Type: Fifty, 50 reales, “Cincuentín”

Year: 1652

Mint: Pamplona Mint

Border: Regular, yet flawed

Edge Engraving: ————–

Metal: Silver, 931 thousandths or 11 money and 4 grains of legitimacy

Diameter: 73 mm, thickness 4.45 mm

Weight: This piece weighs 168.60 gr.

Quantity: The number of copies produced is unknown, but only 4 copies have survived to this day.

Coinage: By casting

Mintmaster: José de Lizarazu, Chief Mintmaster

Recorder: Unknown

The fiftieth one on display at the Museum of Navarre – Diameter = 73 mm; Thickness = 4.45 mm; Weight = 168.60 gr

Obverse: PHILIPPVS VI D GRACIA PA 50

Back: NAVARRE REX ANO 1652

The second piece was put up for sale by the Aureo & Calico auction house on December 15, 2021. The auction price was 55,000 euros and, taking into account the 18% commission, the buyer paid a total of 64,900 euros for this fascinating piece. In my opinion, this piece has received the highest price ever paid for a Basque silver piece, but as we will see, not in this latest sale.

The fifty-year-old 171.76 gr offered by the Aureo&Calico auction house on December 15, 2021 – sold for 55,000 euros

In this case we can enjoy this issue through a video: Video of the Second Pentecost.

This next historical issue was put up for sale by the Numismatica Ars Classica AG auction house in Zurich on March 18, 2002 (it will soon be 20 years old). The photo of the booklet from this sale is below, in this case issue 85 of the Navarre fiftieth. Looking at the photo, I believe that this issue is the same as the one sold by the Aureo&Calico auction house, which is what we call the second issue.

This piece was sold for CHF 130,000 on March 18, 2002. Considering that at that time one euro was worth 1.47 Swiss francs, this would give us a sale price of around EUR 88,000. This would be the highest price ever paid for a Basque silver coin.

Photo of the booklet of the 22nd sale of the Numismatica Ars Classica AG auction house – March 18, 2002 – Issue 85 – 130,000 CHF – 171.43 gr

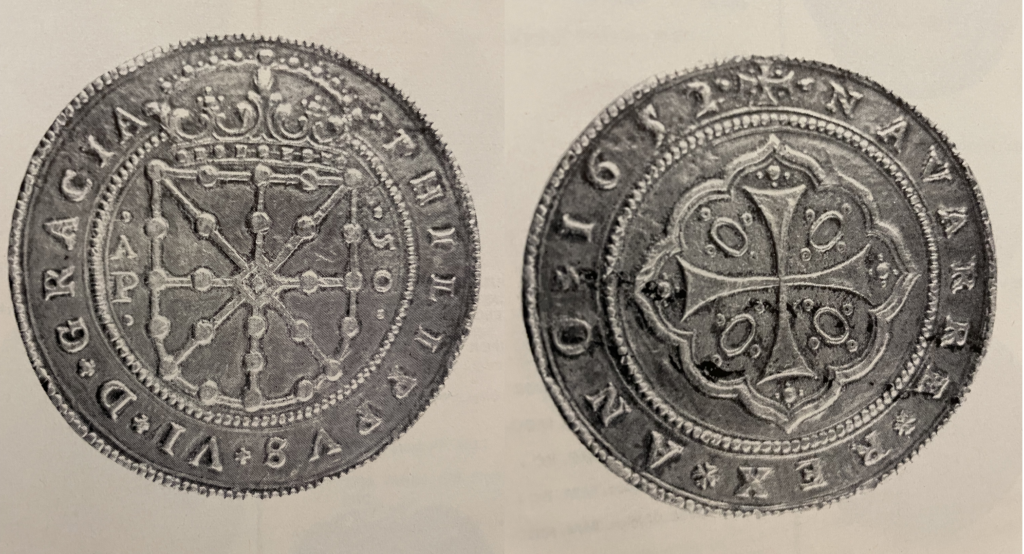

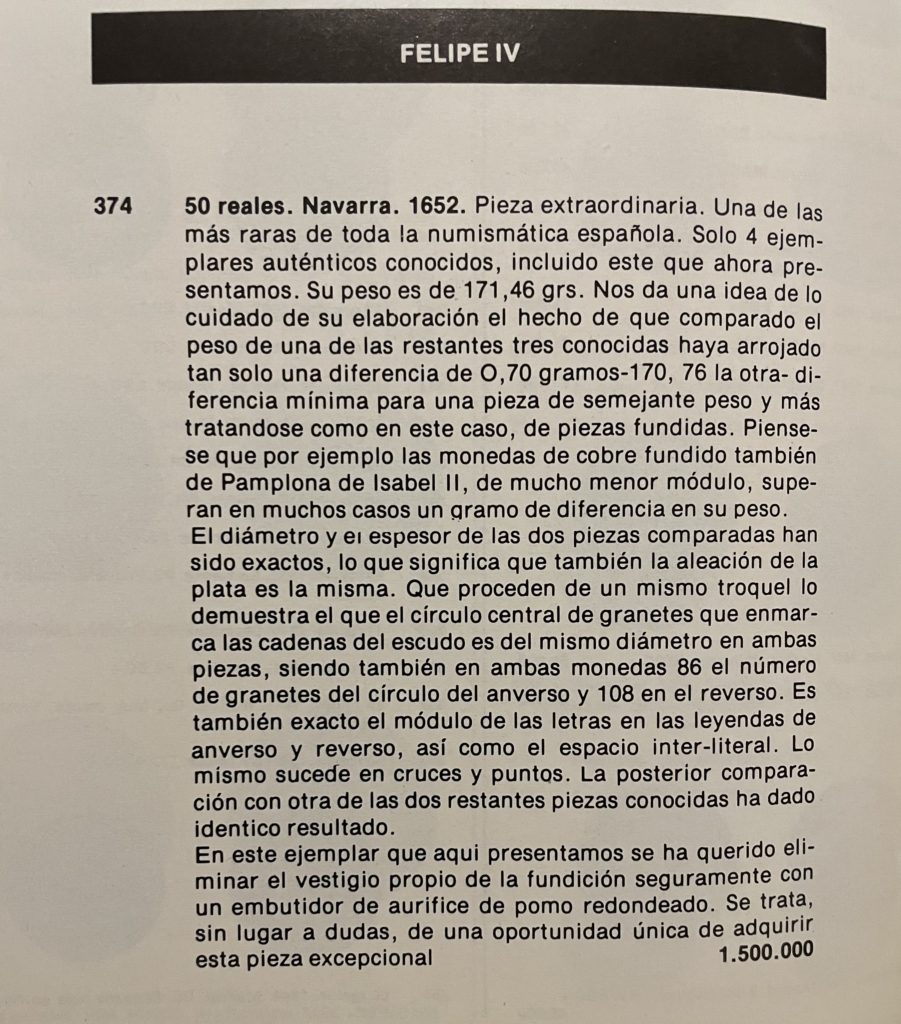

Another historic copy was put up for sale by the Madrid auction house Numinter on April 30, 1981 (soon to be 41 years old). The auction house's booklet referred to the four copies. Here are the photos taken from the booklet:

Numinter auction house: Photo of the 1981 spring sale issue – April 30, 1981 – Issue 374 – Starting price 1,500,000 pesetas (today's 9,000 Euros) – 171.46 gr – Auction price unknown

Numinter Auction House: Photo of the 1981 Spring Sale Booklet – April 30, 1981 – Issue 374

After carefully examining this photo again, I would say that this specimen is the one we have identified as the second specimen. The traces of concretions that appear on the front and back and the traces of blows that appear on the gills would suggest that they are in the same place as in the previous photos, in my opinion. The weight given in the three sales is not exactly the same, but it is very close in all cases (171.76gr, 171.43gr, 171.46gr).

This 374th copy sold at this auction had a starting price of 1,500,000 pesetas (9,000 Euros today). I was unable to find a final price.

A third fifties is said to be in the hands of an anonymous collector who has a large collection of fifties. I have no news of the fourth. As is normal, I have not had the opportunity to collect photographs of these third or fourth copies. According to one of the booklets above, a third copy was in the hands of the Count of Espelette at the end of the 19th century and Alois Heiss included it in his book. Later, a very well-known Navarrese collector is said to have had another copy at the end of the 20th century…but publicly, at least at auctions, no other copies have appeared.

But why and how were these fifty coins made, after the complaint sent by the courts? Some experts believe that these coins were made with the aim of atoning for or balancing the injustices complained of by the courts. And it must be said that both these coins and the later silver coins made in the years 1658-1659 show the image texts requested by the courts. But here too there are a couple of noteworthy details. The courts clearly stated the image text to be used, which is “Philippus Sextus Dei gratia Navarrae Rex" and in the case of coins, “D. GRAC"IA NAVARRE REX" and "ANO" in Latin"anno" Instead, they are documents. This is the Spanish normalization of Latin image texts that is clearly evident in these special coins of fame.

As mentioned, we do not know the number of fifty-ones produced, nor the number of those produced in 1652 or later as a reminder of the court's grievances, or which individuals received a copy. It is clear that they were not produced in large numbers and that only the highest authorities of the Kingdom of Navarre probably received a copy.

But how were they produced? The Pamplona mint did not have the same facilities as the Segovia mint, where the coins were produced by hammer blows and not by rolling and engraving rollers. In Donapaleu, in those same years, they began to produce coin specimens using new flywheel presses, but even the same presses in Donapaleu were not capable of producing these huge specimens weighing around 173 grams.

Thanks to the analysis of the preserved specimens, we can say that these coins were made by casting. However, we do not have much additional information, since we do not know the molds used or the working procedure. After removing the cooled mold, the specimen was cleaned and master engravers used chisels to improve and highlight the edges of the engravings.

The production of these coins would have been a real challenge for the blacksmiths of the Pamplona mint, who probably had to make several mistakes and make changes to the process to produce the coins that have survived to this day. The Navarre Museum preserves a die made for the production of these coins, a die weighing almost ten kilos! We can assume that this die was used in some form of hammer or hydraulic press work, or, for lack of a better alternative, as part of the casting mold or in the process of creating these molds.

The only die of the fiftieth kept by the Museum of Navarre

Height = 280 mm; Width = 115 mm; Diameter = 76 mm; Weight = 9963 gr

Before we finish, a comment from Aska. During the 17th century, the Pamplona mint used chains on copper coins to represent the coat of arms of Navarre. But as we can see in all these silver coins from 1651-1653, the image appears more like a carbuncle than a chain. Coincidence, cheep? As we have seen, coincidence does not usually have a place in coinage, but oh well!

4-cornado coin of King Philip VI of Navarre, 1622 – 3.99gr – The representation of the chains can now be clearly seen

Acknowledgements: The Aureo&Calico auction house provided me with data that was very useful for the preparation of this blog entry. Thank you!

Bibliography:

THE EFFECTS OF THE "GREAT SCANDAL" OF POTOSI IN SPAIN - Francisco Jovel, Roberto Jovel - link

NAVARRE COINS AND ITS DOCUMENTATION 1513-1838 – Jorge Marin de la Salud – 1975

GENERAL CATALOG OF THE MONEY OF NAVARRE – Ricardo Ros Arrogante – 2013 – Altaffaylla publishing house

Provision in which the old currency of Piru, of Reales de a ocho, y de a quatro is prohibited: and it is sent to the register, and all those who own it, in this City of Pamplona are declared under the penalties established in it: and it is ofrece satisfaction pronta de ella a los que la registraren – 1651 March 1. – Binadi – link

Novíssima Recopilación de las Yeyes del Reino de Navarre (Pamplona 1735) Volume II, BOOK V, TITLE VI: OF THE CURRENCY (LAW XII) – link

Quaderno de las leyes, ordinanzas, prouisiones, y agrauios repaired at the request of the three States of the Kingdom of Navarre, in the Cortes of the years 1652, 1653, and 1654 by ... Felipe Sexto : con acuerdo de los del Consejo Real ... y Cortes , which were celebrated in this city of Pamplona - Law 51, page 105 - Binadi - link

LA COLECCIÓN DE UTILES DE ACUÑACION DEL MUSEO DE NAVARRA – Numerous authors – 2003

CINCUENTIN DE PAMPLONA 1652- NUMISMATIC BLOG – Adolfo Ruiz Calleja – link

GENEALOGY OF LOS LIZARAZU, CONDES DE CASA REAL DE MONEDA – Iñaki Garrido Yerobi and Jorge Rivera Sánchez – 1998-1999 – link

All personal data collected on this blog will only be used to disseminate the contents of this blog. Personal data will never be transferred or sold to third parties. You can unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the link in the footer of our emails.

Excellent!

I didn't know this blog and finding it has been a pleasant surprise. It's great to have a blog dedicated to the Navarre coin.

Thank you!!

Adolf

Thanks for the episode Adolfo! We are all indebted to your magnificent work of divulgation of numismatics, this same entry has used your material!

Pingback: Peruvian Silver Scam in Navarre

Pingback: 1589, the Year of the Three Kings | History of Basque Coinage