I had a break of a couple of months before writing a new entry for this blog. During this break we moved house. We have been working on building a little house for a long time, intending to move closer to the Munitx area, and finally the time has come to live in it. For those who have the image of us in the Basque Country being clumsy and messy and Germany being a country of efficiency, I would be happy to share my anecdotes…but that will not be on this blog.

In today's article, we'll talk about a couple of coins that I've had on my mind for a long time. They are the link to this story that has fascinated me since I found one of these coins in a drawer in a farmhouse as a child. That coin was a 2 pesetas coin from the Basque Government during the civil war. How one of these ended up in a drawer in a farmhouse in the Goierri region is completely unknown to me.

But, what is the history of these coins bearing the name of Euzkadi, who, how and where were they minted and for how long were they issued?

To be honest, when I decided to write about the coins of the Basque Government, I thought I would settle the matter in a couple of pages, as there was no great mystery to the history of these coins.

Although there is often a complete lack of contemporary documents and orders regarding coins minted in the Basque Country, in this case, I realized that the Basque Government archives make a beautiful collection of documents and orders available.

By reading these documents, there are details that need to be written here too! I have learned unknown and interesting details that I have not seen anywhere else, juicy stories, which are reflected in the following. Moreover, anyone can access these documents, through the links provided in the bibliography section and can form their own opinion on what will be told below.

I found a similar 2 pesetas coin ordered by the Basque Government many years ago – 8 gr, 26 mm

Front: GOVERNMENT OF THE BASQUE COUNTRY AB

Back: 2 PESETAS 1937

Driven by the emergence of paper money in the second half of the 19th century, but especially by the debt accumulation and economic crisis after the First World War, the monetary systems of countries around the world underwent a complete transformation in the 20th century. Coins went from having intrinsic value to becoming fiduciary coins, that is, coins of good faith. In essence, they went from having a nominal value of the value of the metal they contained to having a nominal value that was much greater than the value of the metal they contained.

A modern euro coin does not contain the metal value of about one euro. Today, it costs much less to mint a euro coin than one euro; but this was not the case until the 20th century. The 5-peseta silver duros used by our great-grandfathers contained an amount of silver that was worth about five pesetas at the time (at least in this case, metal values also fluctuated).

One of the last silver 5 pesetas minted during the reign of King Alfonso XIII. These coins had intrinsic value, meaning the value of the silver contained in them was around their face value – 25 gr, 37mm, 900 thousandths of silver. 13,929,660 coins of this type were minted this year

Front: ALFONSO XIII POR LA G. DE DIOS 1899 *18 *99

Back: REY CONSTL. DE ESPAÑA SG 5 PESETAS V.

The last silver peseta minted by the pre-war republic was minted between 1933 and 1934. This peseta had the same pattern, weight and dimensions as the peseta minted in 1868, but the economic crisis that began in 1929 and the loss of value of the peseta caused by the political crisis of the Spanish state made it clear that it was necessary to abandon the intrinsic value system and move towards a fiduciary system.

The last silver (835 million) pesetas coin minted by the Spanish Republic in 1934 – 5 gr, 23.30 mm

Front: REPUBLICA SPANISH 1933 *19 *34

Back: ONE PESETA

Instead of the historically used gold, silver, and copper or bronze, fiduciary systems encouraged the use of new metals and alloys. Among the new alloys were alloys of copper and nickel, or copper and aluminum, and among the new metals, coins made of pure nickel began to be minted in other European countries. For example, the Royal Mint of Belgium began minting pure nickel 5 franc centime coins in 1894.

The outbreak of the Spanish Civil War led to a crisis in the circulation of money. On the one hand, it led to the disappearance of the silver and gold pesetas minted since 1868. Faced with the insecurity brought about by the war, people hoarded precious metals at home. This moment was the starting point for the silver duro treasures inherited from our grandparents and great-grandparents.

On the other hand, small bronze coins, called small dogs and large dogs, were not sufficient for daily trading needs and in some cases, these were also demanded to meet the needs of war.

Our Grandparents' Big Dogs, 10 Pesetas Centimes Bronze Coin – 10.0gr, 30mm

These coins remained in circulation until the end of the war.

As a result of these factors, the shortage of coins necessary to meet daily needs became increasingly acute immediately after the outbreak of war.

The situation was even worse in the territories of the Republic around the Cantabrian coast, under the control of the Council of Asturias, the Council of Cantabria and the Basque Government. After being isolated from the rest of the Republic and the French border in the summer of 1936, they were separated from the Bank of Spain and the institutions in Madrid that were responsible for the coins and banknotes.

After the approval of the Statute of Autonomy of the Basque Country in the Madrid courts on October 1, 1936, and the formation of the first Basque Government on October 7, the new government began to seek a solution to the problem of the shortage of coins and banknotes.

In the case of banknotes, an issue of 130 million was made and the printing in this case was done by the Bilbao-based printing house “Huecograbado Arte y Editorial Vasca SA” (If you want to take a first look at the banknotes, click here). link). Banknotes of 5, 10, 25, 50, 100, 500 and 1000 pesetas were created, although the last two were not issued. It should be noted that all the banknote issues carried out were guaranteed by the Bank of Spain.

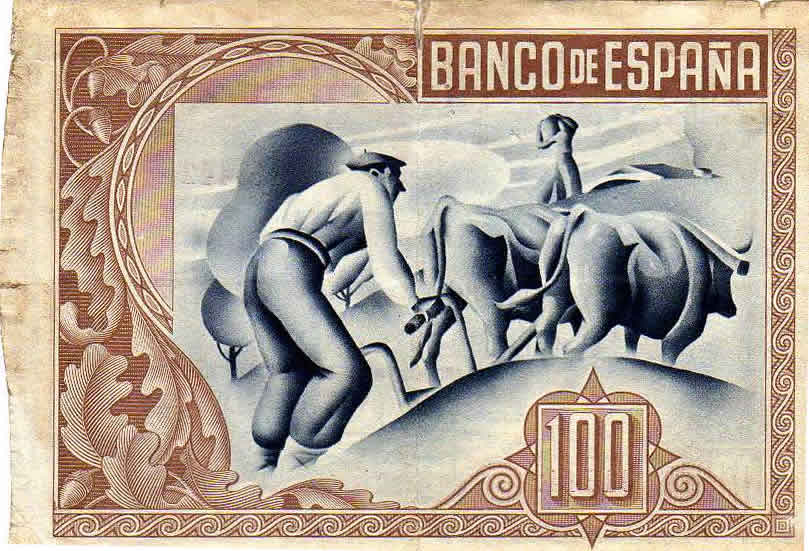

Image of the 100 pesetas banknote minted and issued during 1937 – Jean Michel Etchecolonea- Wikipedia Commons

But the underlying theme of this blog is coinage and we will not, at least today, talk about paper money.

As we have said, the Basque Government began to try to solve the problem of the shortage of coins immediately after its formation. Initially, it was thought that coinage would begin in local factories, in workshops in Eibar, Gernika or Bilbao. However, the purchase and transport of metal required by the number of coins to be minted, and the time delays that would arise from the low production capacity of local workshops, gave rise to the idea of working with foreign mints. In the end, the decision was made to transport the coins minted and minted abroad to the Basque Country as quickly as possible.

Mandate to contact foreign mints Rafael Picavea, the head of the Basque Government delegation in Paris, was received by the Gipuzkoan leader. Picavea sought the help of the banker Leon Lilienstern, whom he knew. Picavea and Lilienstern asked three European mints for a budget to produce the coins, including the London mint. Royal Mint, Paris Paris Mint and Brussels Royal Mint of Belgium to (MRB). The budget was to indicate the price of minting 10 million pesetas, 6 million in one-peset coins and 4 million in two-peset coins. As for the metal, the Basque Government's preference was for the use of Nickel, instead of brass or chromed iron.

Of these three mints, the Royal Mint did not even respond. As shown by telegrams sent by the Minister of Finance, Eliodoro de la Torre (known by the nickname Urtantea), at the end of December, and reports made by the Basque Government at the beginning of January, the talks with the Paris mint were already quite advanced.

Initially, the intention was to use the designs of the engraver Nicolas Martinez Ortiz and the text image “BANCO DE ESPAÑA”. However, due to the urgency of the time, Martinez Ortiz’s design was abandoned and the image of the republic and freedom that had been half-prepared for the Paris Mint was adopted. Martinez Ortiz’s originals had images of a warrior and a girl. The coins should have been the size of the silver one and two pesetas, that is, 23mm and 27mm. As we will see later, the specimens finally minted are close to these sizes.

Likewise, due to the lack of authorization from the Bank of Spain, the obverse text image was changed from “BANCO DE ESPAÑA” to “GOBIERNO DE EUZKADI”.

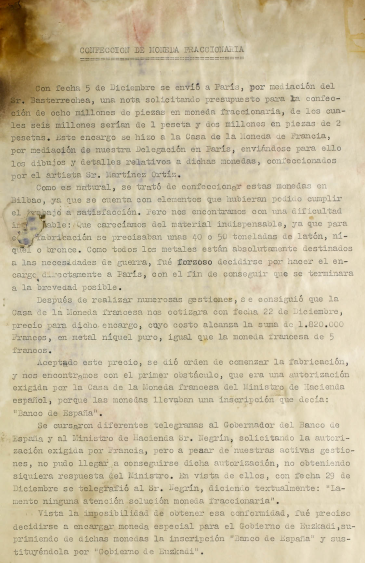

The first page of the report written by the Basque Government in early January on the coinage project

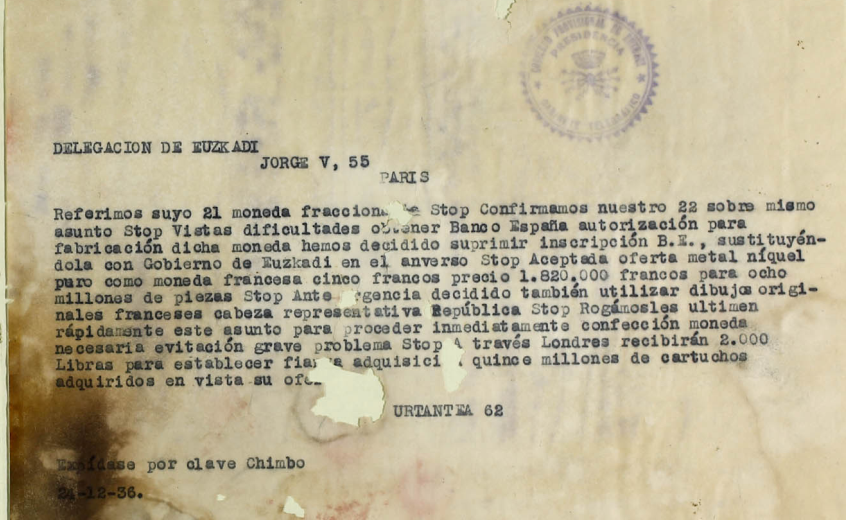

Telegram sent by the Minister of Finance, Eliodoro de la Torre (Urtantea), to the delegation in Paris on December 24th

On December 21, the Paris Mint presented its offer to Picavea at the Splendid Hotel. There were three different offers, depending on the metal chosen. The minting of nickel coins had a budget of 1,820,000 francs, the nickel bronze (75% Cu, 25% Ni) of 1,090,000 francs and the aluminum bronze (91% Cu, 9% Al) of 980,000 francs. In addition to this, an amount of about 80,000 francs had to be added for the work of the engraver, both for the images and for the preparation of matrices and dies. As for the delivery period, a period of six weeks was offered for the nickel minting, but it was also made clear that the Paris Mint recommended the minting of aluminum bronze coins, for which it had the necessary metal on hand. There could have been delays when it came to working on nickel coins, and it is also worth noting that the engraver's work would have required an additional period of about three weeks.

French 5 Francs Lavrillier type – Nickel 31mm, 12gr – Coin mentioned in the Paris Mint offering

FRONT: REPUBLIC OF FRANCE

BACK: RF 5 FRANCS 1937

The Bilbao government and the finance minister De la Torre agreed with the budget provided by the Paris Mint for the production of nickel coins. At the end of December and the beginning of January, they confirmed the plans and provided the Paris delegation with the necessary funds. They also tried to ease the necessary authorizations before the French and Spanish Republican governments.

In Bilbao, they had no news of any other offer, no news from the Belgian mint. On January 7, the Bilbao government believed that the request had been made to the Paris mint.

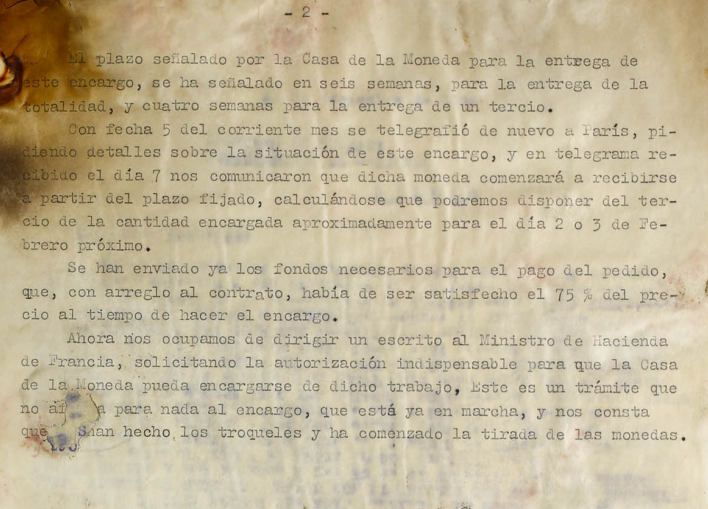

The second page of the report written by the Basque Government in early January on the coinage project –

On January 7th, there is still talk about the Paris Mint.

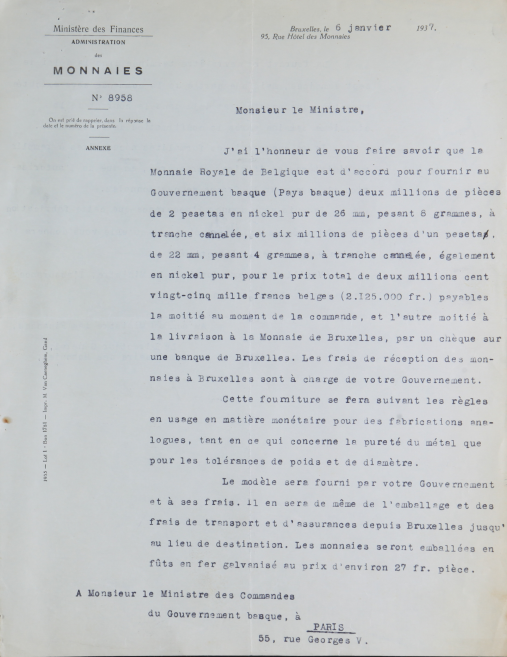

At this moment and suddenly, the first document of the Belgian Mint appears for the first time in the archives of the Basque Government, dated January 6, 1937. In a letter written to the Paris delegation, the head of the mint, Hector Verhaeghe, offered a budget of 2,125,000 Belgian francs. This budget reflected the cost of minting 6 million (22mm and 4 gr) nickel pesetas and 2 million (26mm and 8gr) two-pesetas. If expressed in French francs, this would be 1,490,000 French francs, considerably cheaper than the offer from the Paris Mint. This offer did not include the cost of the engraver's work. In fact, on that very day in January, Lilienstern and the engraver Armand Bonnetain were present in the presence of Mr. Verhaeghe, and they made it clear that they would take on the work of the images and matrices.

Regarding the delivery period, the coinage would be fully completed in seven weeks.

Budget sent by Hector Verhaeghe, head of the Brussels Mint, to the Paris Delegation – January 6, 1937

From this moment on, the name of the intermediary named M. Ferdinand Mayer (MF Mayer) appears everywhere in this history. According to Picavea himself, the banker Lilienstern introduced this intermediary to him at the beginning of January. He was supposedly under Lilienstern's authority and, due to the latter's numerous duties, he was entrusted with the mediation of relations between the Belgian Mint and the Basque Government.

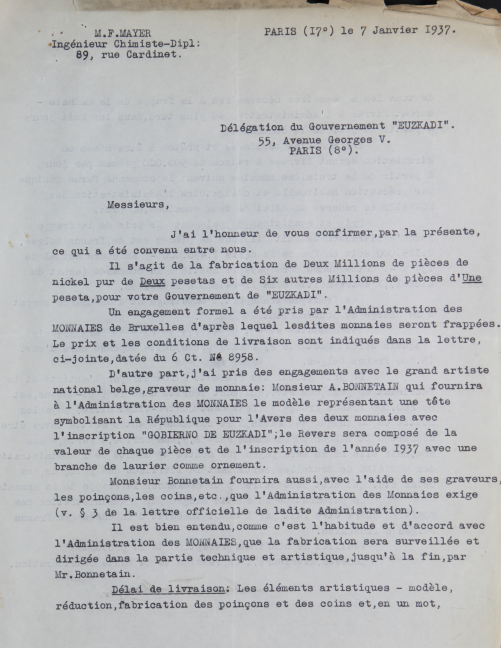

On January 7, as both Picavea and Mayer confirmed, they jointly wrote a general proposal addressed to the Paris delegation. The proposal, which was accepted as it was and which is the focus of subsequent events, will be presented below:

Page 1 of the proposal sent by Mr. MF Mayer to the Paris delegation – January 7, 1937

The first page of the proposal refers to the budget presented by the Brussels Mint. It also names the Belgian engraver Armand Bonnetain as responsible for the artistic execution and the production of the dies and dies. It describes the general characteristics of the coins that we will see today and finally goes into details about the delivery period.

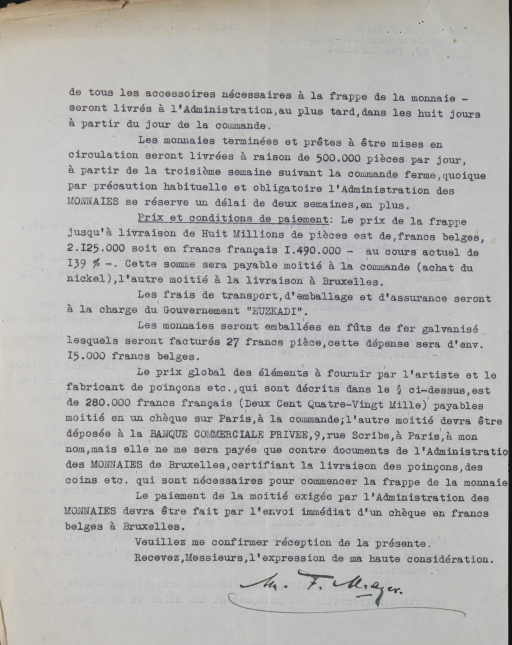

Page 2 of the proposal sent by Mr. MF Mayer to the Paris delegation – January 7, 1937

All the dies, dies and accessories needed for the production of the coins were to be delivered by Mr. Bonnetain within eight days of securing the order. Three weeks after receiving the order and the necessary dies and dies, the Belgian Mint would begin delivering the coins, at a rate of half a million pieces per day.

As mentioned in the previous letter, the price of the minting was 2,125,000 Belgian francs, or 1,490,000 French francs. Half, or 1,062,500 Belgian francs, or 745,000 French francs, was to be paid with the shipment of the coin and the other half upon receipt of the coins. The costs of transport, insurance and packaging would be borne by the Basque Government.

The last point was the remuneration that the engraver was to receive for his artistic and technical work. This shows a head-scratching figure of 280,000 French Francs, half of which was paid immediately after the order was placed, and the other half after the delivery of the dies and dies. This figure is very significant, compared to what the Paris Mint had stated. three and a half times It is greater, in this area, although the budget of the Paris Mint already seems a bit expensive.

Model of the obverse of the coin, plaster cast by Armand Bonnetain, patinated bronze – Below the female model of the Republic, the intertwined initials AB (Armand Bonnetain) can be seen – Didier Vanoverbeek, Luc Vandamme

The front matrix that created the dies used in the production of 2 Pesetas coins – Didier Vanoverbeek, Luc Vandamme

The dies used in the production of 2-pezetta coins created the matrix on the back – Didier Vanoverbeek, Luc Vandamme

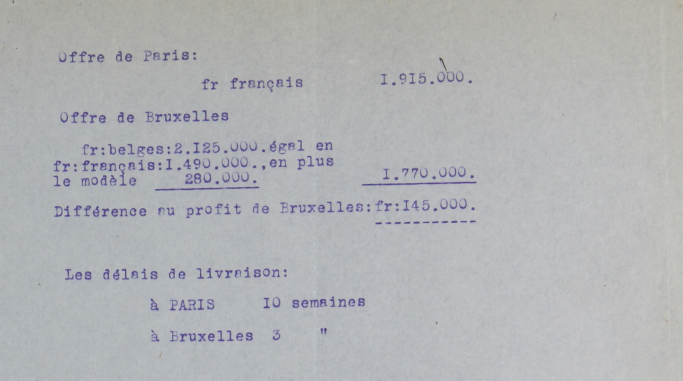

Among the papers found in the Basque Government archives, the following cost comparison can be found. It has no date or author's name.

Analysis of the offerings of the Paris and Brussels mints – Undated and authorless

In this comparison, in the case of the Paris mint, there was no description of the different sub-series costs, on top of the 1,820,000 francs, 80,000 francs for artistic and technical work and probably packaging costs were added. In the case of the Brussels mint, the sub-series costs were described but not the packaging costs. The analysis showed that the Brussels mint's offer was 145,000 francs cheaper. However, this offer would have been even cheaper if the costs of the inflated dies, matrices and artistic work had remained within reasonable amounts. In the case of delivery time, the conservative Paris case was compared against the optimal Brussels case.

Since the analysis is written in French, we can assume it is the work of Mayer or Lilienstern.

As a curiosity, here is some data. Including transport and insurance costs, we can calculate the cost to the Basque Government of this coinage at around 2,000,000 French francs. 100 French francs had an exchange value of around 48 pesetas during 1936. After the outbreak of war, the exchange value would probably have shifted in favor of the franc, but we can still say that the cost of minting 10,000,000 pesetas was around a million or more, a million and a half pesetas.

On January 9, Justo Zubizarreta, commercial representative of the Paris office, paid 1,062,500 Belgian francs to the Monnaie Royale de Belgique (budget item 50%). On the same day, he paid 140,000 French francs to Mr. Mayer, payment for artistic and technical work item 50%.

On January 12, the Brussels Mint confirmed to the Basque government delegation in Paris that it had received Armand Bonnetain's tools. From that day on, the delivery period began to count. Between February 5 and 10, the Belgian Mint planned to deliver the first batch of 500,000 coins and the entire minting should be ready by February 23. Therefore, in mid-January, the Brussels Mint was already ready to start minting the coins, waiting for the coin dies to arrive by February 5. On February 5, the Basque Government sent the Belgian Mint a second payment of 562,500 Belgian francs in exchange for the first shipment of coins that was about to be issued. The last payment of 500,000 Belgian francs was made the day before the last shipment on March 13.

The coin puddings or cospels were created by the company „SA des Usines à Cuivre et à Zinc de Liège“ of Liège and distributed to the mint. As the work of Domitilo Tristan shows, the coin puddings were created by cutting nickel (99/99.5% Ni + Co) cylinders produced by the company „Société Générale des Minerais SA“ of Liège.

Since Armand Bonnetain had already delivered the necessary dies and dies to the Brussels Mint, Mr. Mayer received the second payment of 140,000 French francs on January 15th.

As various works by Didier Vanoverbeek, a former employee of the Brussels Mint, show, these matrices and dies were made in the workshops of Alexandre Evaraerts, head of the engraving service. For these works, he was assisted by three employees of the mint who received a salary of 447.50 francs in compensation for overtime worked. Most of the information sources that appear in the Basque Government's archive papers indicate that Armand Bonnetain's salary was between 25,000 and 35,000 francs.

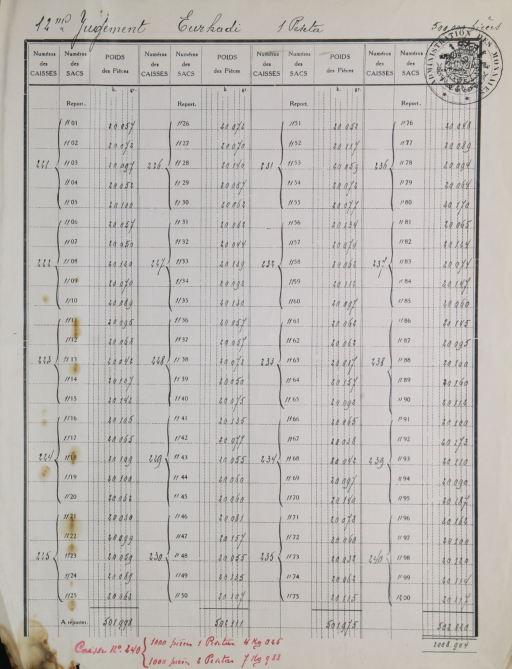

The coins were delivered in iron-reinforced boxes. The dimensions of these boxes were 32 x 32 x 55 cm and each box contained five sacks of coins. Each sack of coins contained 2,500 pieces of two pesetas, or 5,000 pieces of one peseta. Consequently, each sack weighed 20 kg and each box contained 100 kg of coins. Each empty box weighed 10 kg, and consequently each box full of coins weighed 110 kg.

Each 2-peseta sack bore the mark "GOBIERNO DE EUZKADI" in blue; in the case of the 1-peseta sacks the same mark appeared in red. As for the boxes, they bore the mark "MRB Monnaie Royale de Belgique", and the colour of the pictorial text was red or blue, depending on whether the contents of the 1-peseta or 2-peseta sacks were in fact one or two pesetas.

The number of boxes of two pesetas was 160 and that of one pesetas was 240, and each box had its own number. Each bag of money also had its own number: from 1 to 800 for the 2 pesetas and from 1 to 1200 for the 1 pesetas. In total, there were 16 tons of 2-pesetas coins and 24 tons of one pesetas, a total of 40 tons, or more precisely 44 tons, if we take into account the weight of the boxes and bags that carried the coins.

List of boxes/bags of coin issuance produced by the Brussels Mint, along with the weight of each bag – Boxes of one pesetas are shown, numbered 221 to 240.

According to Didier Vanoverbeek, a former employee of the Brussels Mint, 24,074 kgr of one-pesetas and 16,047 kgr of two-pesetas were minted. According to the lists in the archives, a total of 6,000,1000 one-pesetas and 2,000,1000 two-pesetas were minted. These two thousand additional coins were included in box 240, the last box delivered.

Regarding the transport of the coins, I have seen many confusions and errors in the articles I have read. Most of them say that two shipments of coins were made, the first by train, 10 tons on the way to Toulouse, and the second by ship from Antwerp to Bilbao, with the remaining coins. It is true that on paper, preparations are made to send 10 tons to Toulouse, but in the end this plan was not carried out.

The coins had two different routes. On the one hand, they were transported by train to Bordeaux or Bayonne and from there they were sent by ship to one of the ports on the Biscay coast. On the other hand, they were transported by ship from the port of Antwerp to the port of Bilbao.

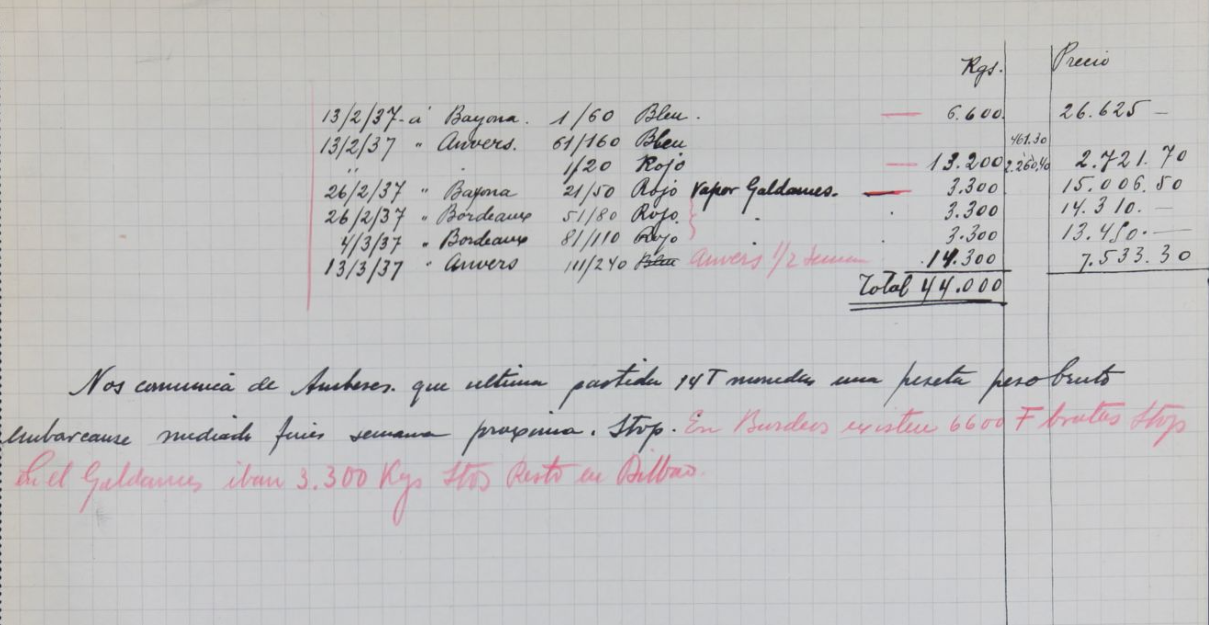

A total of six shipments were made and since the invoices issued by the carrier are kept in the archive, the following summary can be made:

- February 13on: 60 boxes of 2 Pesetas (1/60) were sent by train to Bayonne. 6 tons of coins, total weight 6.6 tons.

- February 20on: 100 boxes of 2 Pesetas (61/160) and 20 boxes of 1 Pesetas (1/20) by ship from Antwerp to Bilbao. 12 tons of coins, total weight 13.2 tons.

- February 26on: 30 boxes of one pesetas (21/50) by train to Bayonne. 3 tons of coins, total weight 3.3 tons.

- February 26on: 30 boxes of one pesetas (51/80) by train to Bordeaux. 3 tons of coins, total weight 3.3 tons.

- March 4on: 30 boxes of one pesetas (81/110) by train to Bordeaux. 3 tons of coins, total weight 3.3 tons.

- March 13on: 130 boxes of one pesetas (110/240) by ship from Antwerp to Bilbao. 13 tons of coins, total weight 14.3 tons.

MF Mayer himself was responsible for the transport and media brokerage. He used the transport agency of Mr. Louis Bielmair for all transport, with the exception of the ships leaving Antwerp. In the case of the ships, the Basque Government itself was responsible.

Although the date of the second shipment is incorrect, the following paper preserved in the archive presents a nice summary, along with the amounts of money each shipment cost.

Manuscript showing a summary of coin shipments – The colors indicate the type of coin, “Bleu” Two Pesetas, “Rojo” One Pesetas – The name of the steamer Galdames appears next to the shipment to Bayonne on February 26th – Basque Government Archives

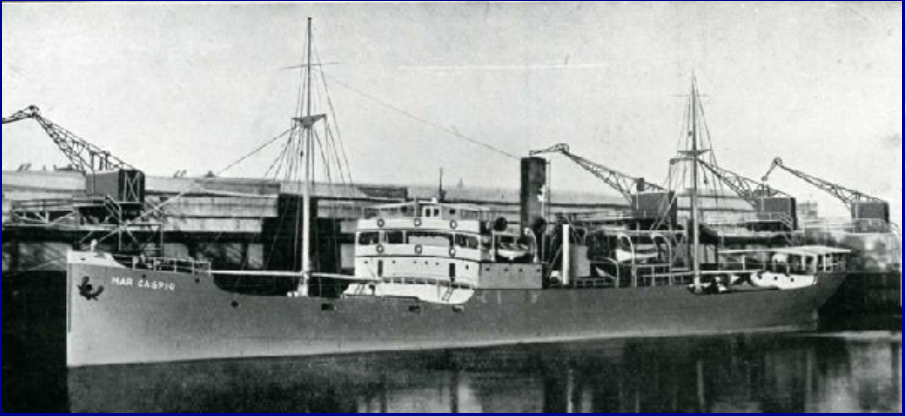

The 60 boxes of 2 pesetas sent by train to Bayonne on February 13th arrived from Bayonne to Bilbao on the steamer “Mar Caspio” on February 20th.

Photo of the ship Mar Caspio. This steamer of the Basque Navy sank in the mouth of the Atturri River on March 29, 1937 – work of the website buques.org

Photo of the ship Mar Caspio. This steamer of the Basque Navy sank in the mouth of the Atturri River on March 29, 1937 – work of the website buques.org

On February 20th, 100 boxes of 2 pesetas and 20 boxes of 1 peseta left the port of Antwerp. These 13.2 tons left for Bilbao on the steamer “Sendeja” and although I am not completely certain, I believe they arrived in Bilbao.

Photo of the steamship Sendeja – work of the website buques.org

The 3 tons of coins sent to Bayonne on February 26th were used by the Basque front. famous naval battle They participated in a. On the night of March 4, the steamer Galdames left the port of Bayonne for Bilbao. Among the passengers, mail and a large amount of merchandise, it was carrying 30 boxes of one peseta (numbered 21 to 50), 750,000 coins. On March 5, while it was heading towards the entrance to the port of Bilbao, accompanied by ships of the Basque Navy, it was stopped by the Francoist warship Canarias. The Canarias, resisting the efforts of the Basque Navy's Bizkaya, Gipuzkoa, Donostia and Nabarra gunboats, took the Galdames to the port of Pasaia under arrest. At the same time, the Canarias sank the Nabarra gunboat, which had been trying to free the Galdames until the last moment. The crew and passengers of the Galdames were taken prisoner and in some cases even shot. The most famous case was that of Manuel Carrasco, the representative of the Generalitat of Catalonia. These coins, of course, never reached Bilbao.

The final battle of the ship Nabarra Bou against the warship Canarias, naval battle of Matxitxako – painting by David Cobb

The steamer Galdames – which was taken to the port of Pasaia after being arrested – work of the website buques.org

It is not easy to say how many of these six transports reached Bilbao, at least I have not found adequate information (if any war expert knows, it would be appreciated if they could let me know). The manuscript written in mid-March makes it clear that the three tons from Galdemes were lost, that six tons are still in Bordeaux and that thirteen tons will leave Antwerp in mid-March. The rest (18 tons) are already in Bilbao, so it seems that the first and second shipments reached Bilbao. According to some references, Franco's warships are said to have captured another 130 boxes of coins. If this is the case, these would surely have left Antwerp in mid-March.

In fact, the last shipment leaving Antwerp contained 130 boxes and these were received by the steamers Axpe-Mendi and Anboto-Mendi, 65 boxes each.

Axpe-Mendi steamer – renamed Monte Alberdi in 1939 – work of the website buques.org

Steamer Anboto-Mendi – renamed Monte Amboto in 1939 – work of the website buques.org

I have no trace of these last boxes arriving in Bilbao. Axpe-Mendi is said to have had 65 boxes impounded in the port of Bordeaux; at the end of July, the English steamer McGregor is said to have taken 65 boxes out of the port of Santander with many refugees; these boxes could possibly have belonged to Anboto-Mendi.

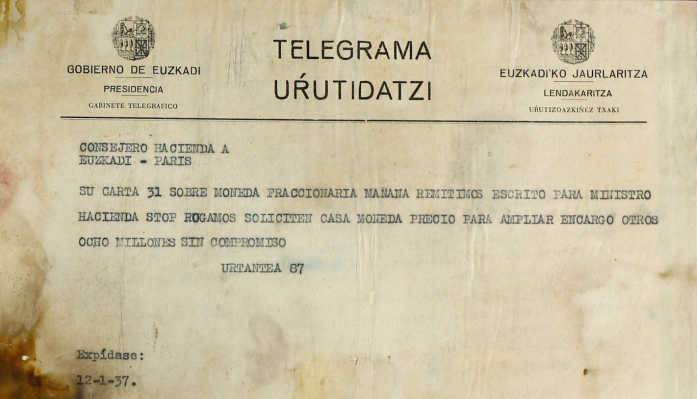

The Minister of Finance, Eliodoro de la Torre “Urtantea”, intended to request a bid for another 8 million copies. This is according to a telegram he sent on January 12th.

"Urtantea" Telegram sent by the Minister of Finance Eliodoro de la Torre to the delegation in Paris on January 12th – Basque Government Archives

In addition to these eight million additional coins, the Belgian Mint also received a request for a tender to mint a new 5 pesetas coin. Accordingly, it sent the following new tender to Mr. MF Mayer, who was acting as intermediary for the Basque Government:

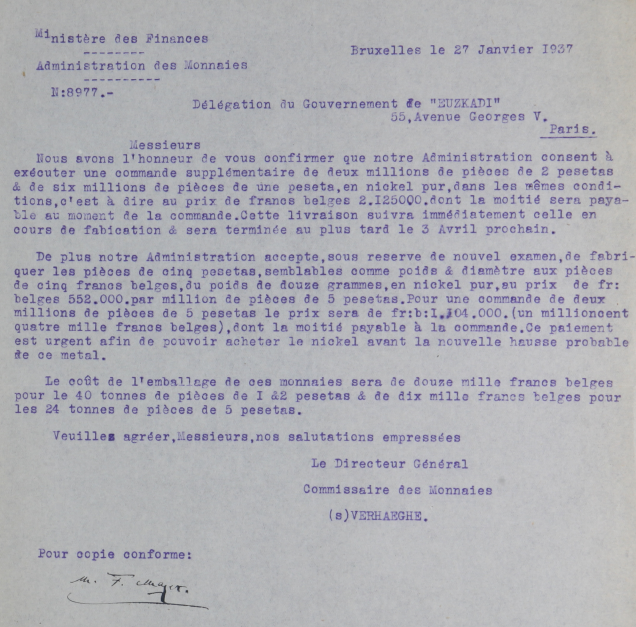

Second offer sent to the Basque Government delegation on January 27th by Hector Verhaeghe, head of the Belgian Mint, through Mr. Mayer – Basque Government Archives

In this offer, the price of 2,125,000 Belgian francs was maintained for the minting of eight million one- and two-peseta coins. For the minting of two million five-peseta coins of twelve nickel grams, the MRB offered 1,104,000 Belgian francs. As can be seen, it was much cheaper to mint ten million pesetas in five-pesetas than in one- and two-pesetas (approximately half the price).

Belgian 5 Franc coin mentioned in the Belgian Mint's offer – Nickel 31mm 12gr – Proof coin

OBJECT: 1936 LEOPOLD III

BACK: BELGIUM 5 FR

The offer that the tenant Mayer made to the Basque Government included an additional 280,000 French francs in exchange for the artistic and technical work on the 5-peseta model. In the case of the one-peseta and two-peseta models, the additional amount was only 20,000 French francs, already quite large but small compared to the previous one (since in this case the artistic and technical work was already ready).

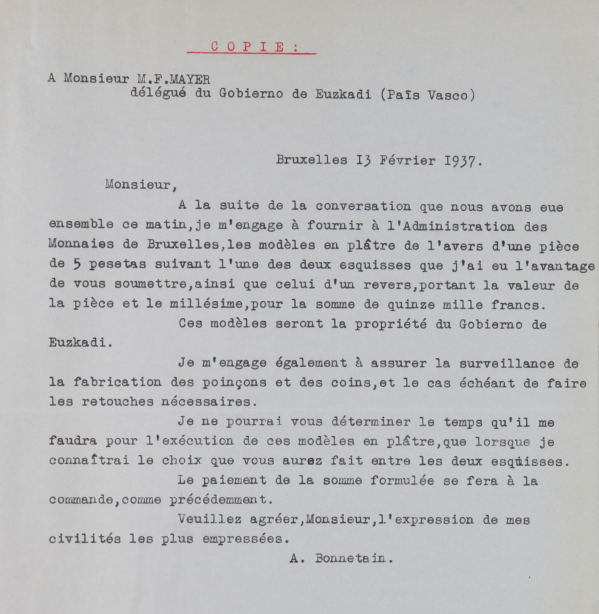

But this time, we have a letter from Armand Bonnetain himself, quite interesting, sent to Mr. Mayer on February 13. In this letter, the engraver Bonnetain explained that he was already working on plaster models of five pesetas coins; the plaster models were being made according to two different front drawings sent to him by the Basque Government. Later, when one of the two models was selected, Bonnetain would direct the production of the necessary matrices and dies, as had happened in the previous order. For all these works on the five pesetas model, he set a price of 15,000 francs.

Letter sent by Armand Bonnetain to Mr. Mayer on February 13th regarding the design of the 5 pesetas coins – Basque Government Archives

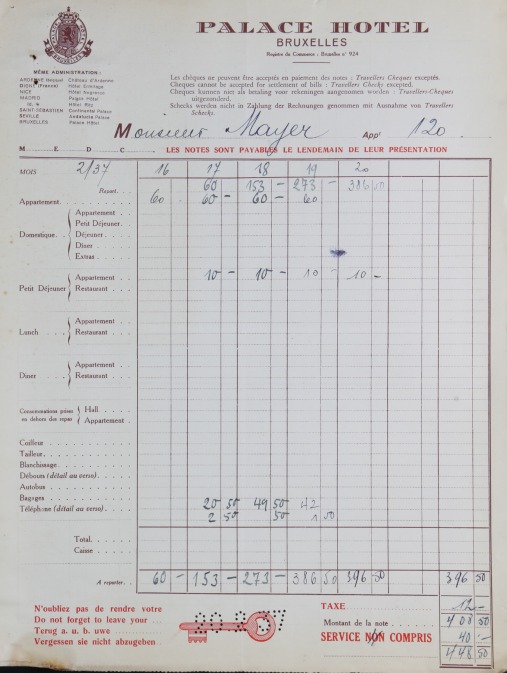

Mayer was once again involved in fraud. To understand the extent of these sums, the hotel bills that Mayer himself sent to the Basque Government as allowances are very useful. A night at the luxurious Palace Hotel in Brussels cost 60 Belgian francs in 1937; breakfast at the same hotel cost 10 Belgian francs.

Hotel invoice sent to the Basque Government by Mr. Mayer – Palace Hotel, Brussels, stay between February 16 and 20 – Basque Government Archives

During the month of February, Mayer tried to sell two other new projects to the Basque Government. The first was about the creation of postage stamps and the second about the creation of paper money. Both of these offers, as far as I know, did not receive a response.

Finally, there was no second minting of coins, nor any new minting of one, two or five pesetas. I have no information about the models of the five pesetas, at least I have not found any traces of the models prepared by Armand Bonnetain or the drawings sent from the Basque Country.

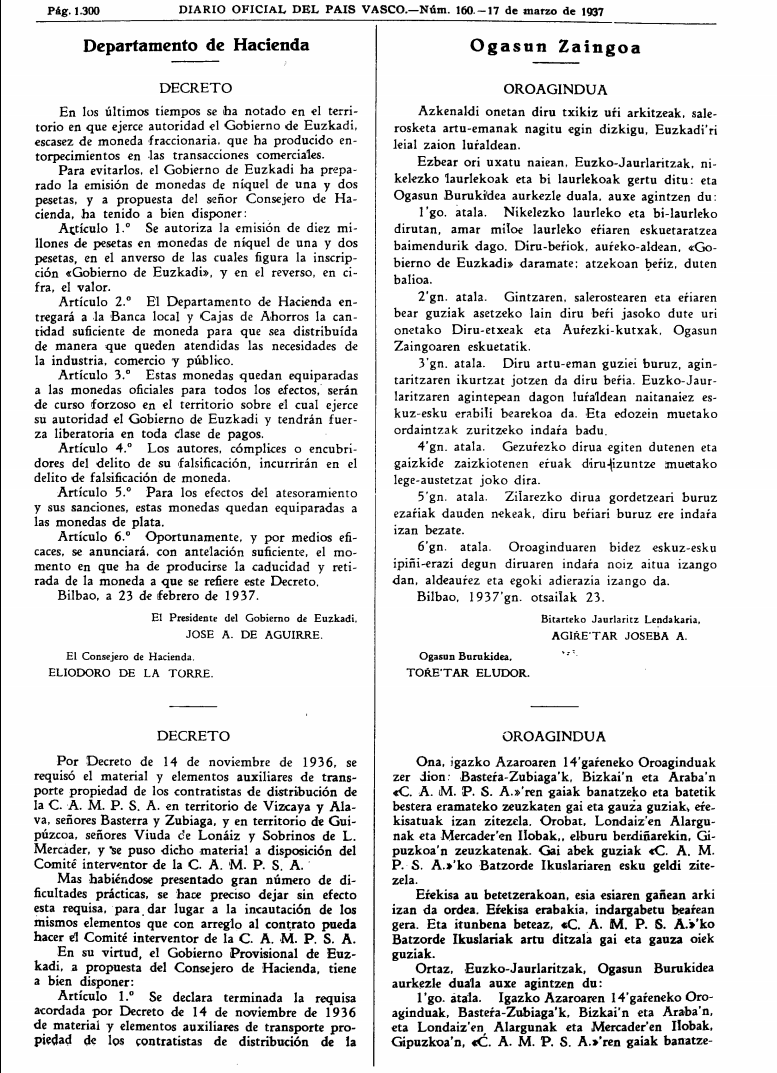

According to the order signed by President Agirre and Minister De la Torre on February 23 and published in the Euskadi newspaper on March 17, one and two pesetas were issued. These pesetas fourth They were called in Basque, meaning four reales, still a reminder of the monetary system before the peseta. This is also where the name of the hogle coin, five pesetas, comes from.

Coin issuance order signed by President Agirre and Finance Minister De la Torre on February 23, 1937

This order marked the release of the only official coins minted under the name of Euzkadi to this day. If we take into account that the National Army entered Bilbao on June 19, these coins were circulated for about four months in the territories under the control of the Basque Government. If we accept that the coins were accepted in the council territories of Santander and Asturias, this period can perhaps be extended by another four months.

As can be seen, this time too, Basque did not have the opportunity to find its place; not even in these issues prepared by the Basque Government itself.

Let's review the characteristics of these coins again:

A set of Basque pesetas sold by the Aureo & Calico auction house on the occasion of the Feast of Saint Fermin in 2015 – One nickel peseta and two pesetas in the upper part – Rare copper alloy proofs in the lower part – Priced at 2,200 Euros

Victory: Civil War, Basque Government rule

Type: One peseta, two peseta

Year: 1937

Mint: Royal Mint of Belgium (MRB), Brussels Mint

Border: Grooved

Edge Engraving: ————–

Metal: Nickel (99/99,5% Ni + Co)

Diameter: 22 mm (1 Pesetas), 26 mm (2 Pesetas)

Weight: 4 gr (1 Pesetas), 8 gr (2 Pesetas)

Quantity: 6,000,1000 (1 Pesetas), 2,000,1000 (2 Pesetas)

Coinage: Coinage through modern machines

Mintmaster: Hector Verhaeghe

Recorder: Armand Bonnetain (AB izki interlinked)

Front:

Front Words: GOBIERNO DE EUZKADI AB

Obverse Description: A woman wearing a Phrygian headdress, facing right, surrounded by a pearl border. This image is an allegory of both freedom and the republic. The Phrygian headdress was worn by freed slaves in the Roman Empire and was adopted by the Jacobins during the French Revolution. Today, the female symbol of the French Republic, Marianne, still wears a Phrygian headdress. At the bottom of the coin are the letters AB, a hallmark of the engraver Armand Bonnetain.

Back:

Back Words: 1 PESETA 1937, 2 PESETAS 1937

Reverse Description: Texts indicating the value of the coins and the year of minting, surrounded by a border of pearls and a laurel wreath.

As we have seen in the previous image and as Domitilo Tristan himself presented in his work, at least two sets of coins made of other alloys instead of Nickel are known. These sets tend to fetch high prices at auctions (Nickel coins are, on the other hand, very accessible today and can be purchased for a few euros). I have found only one mention in the archive about the reason for these coins being made of a copper alloy.

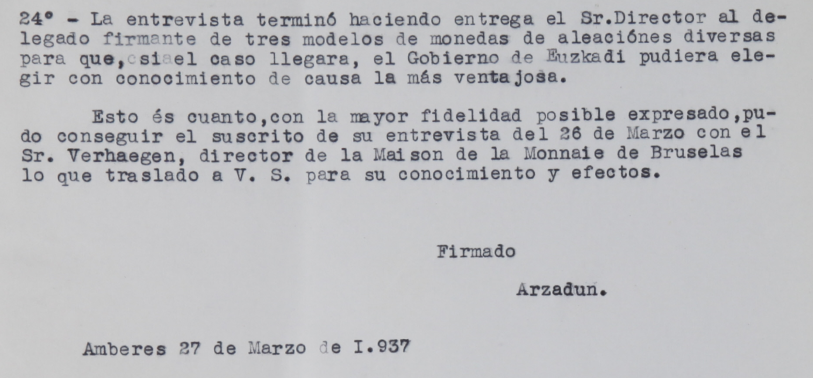

During a meeting with the head of the mint, Hector Verhaeghe, on March 26, the Basque Government's delegate to Arzadun reportedly gave Mr. Arzadun three sets of coins of different alloys so that the Basque Government could decide between more options for future minting.

The final point in the report drawn up by Mr. Andres de Arzadun following the meeting with Hector Verhaeghe on March 26th – Basque Government Archives

But the jokes surrounding these coins did not end there. Why, precisely, did Mr. Arzadun interview the head of the mint, Hector Verhaeghe, on March 26?

In the documents and writings that we have shown in this introduction, anyone would have already noticed the inflated budget, poor verification of expenses and the use of other bad practices. These could have remained as they are, but on March 6, when the Paris delegation informed Mr. Mayer that a second coinage job would not be given, a storm was about to break out.

Mayer worked as an intermediary in the transport of coins, and joined Mr. Lilienstern in all these transactions as an assistant. However, the profits did not seem sufficient to him, or as it seems, he expected greater ones, especially in view of the second minting that was to be carried out. When his expectations were dashed, on March 13, he sent the following letter to the Basque Government:

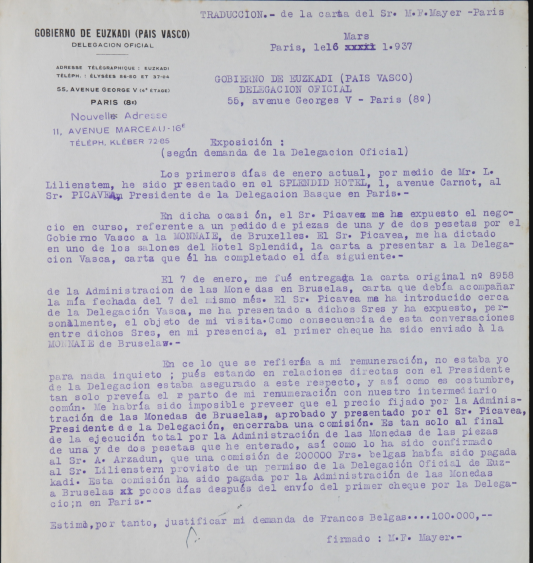

Translation of the letter sent to the Basque Government by Mr. MF Mayer on March 13th – Basque Government Archives

In this letter, Rafael Picavea, Leon Lilienstern, and others made strong statements about the price and payment of coinage. Let us examine the ideas developed:

- He does not present himself as an employee of Mr. Lilienstern, but as a free intermediary.

- Mr. Leon Lilienstern explains that after introducing Rafael Picavea, he wrote the offer to be presented to the Basque Government and gave it to Mayer. This can be confirmed by examining several references that can be found in the archive. It is worth remembering that this offer included an artistic and technical fee of 280,000 French francs, which was completely expensive and inflated.

- Mr. Picavea guarantees that he introduced Mr. Mayer to the trade councilors of the Paris delegation.

- He alleges that the price offered by the Brussels Mint included a commission of 200,000 Belgian francs, and that this commission was collected by Mr. Lilienstern, with the help of a signed authorization from the Basque Government delegation.

As a result of all this, and in a tone that bordered on blackmail, he demanded compensation of 100,000 Belgian francs from the Paris delegation.

Bold statements in any case, and even bolder if we take into account that Mr. Lilienstern had been spreading rumors that Picavea had given him 900 English pounds out of the 200,000 francs commission he received.

After learning of all this, the Basque Government ordered an investigation through Francisco Basterrechea (father of the sculptor Nestor Basterretxea), the inspector in charge of the delegations. The author of the investigation report was Andres de Arzadun, one of the commercial councilors of the delegation in Paris.

Arzadun met with Mr. Dehez, the controller of the Brussels mint, in mid-March and with the mintmaster, Hector Verhaeghe, on March 26. On March 27, he presented his first report to his colleague Justo Zubizarreta and inspector Basterrechea. The archive contains a second report written on July 9, in which he provided additional information on certain details.

The report clearly stated that the Brussels Mint had paid Mr. Lilienstern a commission of 200,000 Belgian francs. According to the Mintmaster, this commission was not related to the Basque Government's request, but was in return for a second request that Mr. Lilienstern was to bring (or requests from other European governments), but this is not easy to believe. It is incredible that the Mint would pay the sum of 200,000 francs before receiving any advance or security.

It is therefore clear that the mint paid Lilienstern a commission of 200,000 Belgian francs and it is also clear that the budget written by Picavea included a section of 280,000 French francs, of which 25,000 or at most 35,000 francs were for artistic and technical work. All of this ended up in Mr. Lilienstern's pocket and Mr. Mayer knew about all of this (and probably also part of it).

Apparently, Mayer was not happy with the commission money that Lilienstern had given him and turned against the Basque Government for more. The bad practices of the same government put the Basque government in an awkward position and, although Mr. Mayer did not go to court, it gave rise to more than two years of back-and-forth discussions between lawyers.

In the end, the Basque government did not offer Mr. Mayer any money or compensation. It also did not take any action against Mr. Picavea. However, Picavea's public appearances and activities were considerably reduced, starting in the summer of 1937 and especially in early 1938.

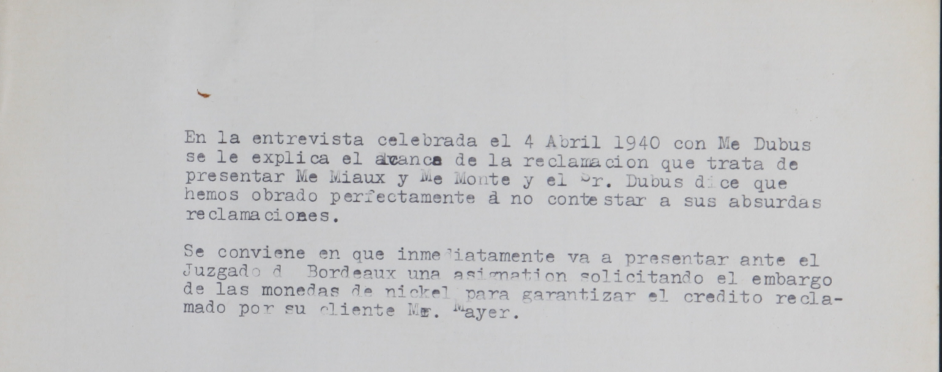

However, after the aforementioned two long years of negotiations and back-and-forth between lawyers, the following was proposed to Mayer's lawyer:

In the court of Bordeaux (although they were physically in a depository in Arroxela) there were 65 boxes of nickel coins (6.5 tons of coins). These boxes, before the fall of the city, were the cargo of the Mac Gregor steamer that left Santander on September 9. They were seized on that day in September 1937 following a court request from the Banco de Bilbao, Banco de Vizcaya and other banks. The Basque Government presented the idea of requesting the ownership of these boxes in court in exchange for the alleged debt to Mr. Mayer's lawyer. Rather than giving them to the banks and nationals, they preferred that the coins fall into the hands of Mayer himself. But I do not think that Mayer received any coins... because the bank always wins, especially when it gets entangled in politics.

Summary of the conversation between Mr. Mayer and lawyer Dubus on April 4, 1940 – Basque Government Archives

Before I end, I would like to say a few words about Mr. Picavea's journey. In the middle of a war, exiled from his home and with few resources, trying to manage everything, it is not easy to structure the representation of a government and at the same time work on the supply of coins, weapons and food.

As head of the delegation, Mr. Picavea, and to some extent the trade representatives of the delegation, made numerous mistakes in the control of money and budgets. Premises are not good travel companions at all, especially in a government structure that was so young.

However, Picave knew, must have known, that the 280,000 French francs for artistic and technical work was completely excessive, and that he was therefore giving Lilienstern money as a gift. I would like to think that he conceived of it as a secret payment for the intermediary services he had provided and would provide... and that he himself had no income from all this.

I would also like to think about the 200,000 Belgian francs that Mr. Lilienstern received from the Brussels Mint. In this case, and until the internal investigation was carried out, I would like to think that Mr. Picavea had no knowledge of these... and that he had no income from all this.

Special thanks to Mr. Didier Vanoverbeek for permission to use the photos and information.

Bibliography:

VASCA PESETA – Wikipedia – link

1937-2002: BEGINNING AND FINAL OF THE PESETA TRUSTEE – Dr. D. Rafael Feria – link

Documentation processed by the General Secretariat of the Treasury on the problem of the shortage of fractional currency and the issue of fractional currency. – link

Documentation, dated between December 16, 1936 and July 30, 1937, processed by the Delegation of Paris on the manufacture by the Belgian Mint of 1 and 2 pesetas pieces for the Government of Euzkadi. Also, on the request presented by MF Meyer, the intermediary appointed by the Government to carry out the mentioned work, for a commission for the services performed. – link

Documentation processed by Ángel Pérez de Anuzita on the lawsuit filed before the French courts against the Government of Euzkadi by a certain Meyer claiming a commission for the work carried out for the manufacture of fractional coins for the Basque Government in Belgium. Due to the demand, the quantities of nickel coins evacuated by the Government of Euzkadi on board the steamer "Mac Gregor" were embargoed. – link

RAFAEL PIKABEA – Wikipedia – link – link

RAFAEL PICAVEA LEGUIA – CIVIL WAR AND EXILE OF AN INDUSTRIAL AND POLITICAL VASCO (1936-1946) – Ander Delgado – 2010 – link

FRANCISCO BASTERRECHEA – Wikipedia – link

NEW DATA ON THE EVOLUTION OF THE PESETA BETWEEN 1900 AND 1936 COMPLEMENTARY INFORMATION – Bank of Spain – P. Martinez Mendez 1990, – link

DE MUNTEN VAN DE HAND VAN ARMAND BONNETAIN – Didier Vanoverbeek, Luc Vandamme – KMB – link

VAN ARENBERG TOT ZANZIBAR BUITENLANDSE MUNTSLAG IN BRUSSELS (1785–2013) – Didier Vanoverbeek -2013 – link

De munten van Euzkadi (Spanish Baskenland) uit 1937 – Domitilo Tristan Jover – DE MUNTKLAPPER – 2021 – link

FORUMS OF IMPERIO NUMISMATICA – Numerous authors and entries, Domitilo Tristan Jover collector – link

Las Monedas de Euzkadi de 1937 – Adolfo Ruiz Calleja – Blog Numismático – link

THE BATTLE OF MATXITXA LUMMUTURRE – Basque Army – link

Production of the Euzkadi Government Coin, issued during the Spanish Civil War (1936 – 1939) – Domitilo Tristán Jover – 2022 – NVMISMA 263

All personal data collected on this blog will only be used to disseminate the contents of this blog. Personal data will never be transferred or sold to third parties. You can unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the link in the footer of our emails.

Pingback: Basque Government Pezeta Issues - Presses, Steamers and Commissions • ZUZEU

Great job!!! Impressive entry!!! Regards

Thank you Roberto, you also do an impressive job. I'll take this opportunity to promote it:

https://leyendomonedasnumismatica.blog/category/carlos-vii-el-pretendiente/