Victory: Charles VII. King of Navarre, Charles IV. King of Spain

Type: Maravedia

Year: 1789

Mint: Pamplona Mint

Border: Irregular, coin-shaped or octagonal

Edge Engraving: ————–

Metal: copper

Diameter: 19 mm

Weight: This specimen weighs 2.71 gr, nominally about 3.04 gr

Quantity: Unknown, the courts of 1781 requested the minting of 12,000 ducats, 4,704,000 maravedi coins

Coinage: By hammer

Mintmaster: Esteban de Espinel, plenipotentiary of the chief mintmaster

Recorder: Unknown

Front:

Front Words: CAROLUS+VII+D+G.

Obverse Description: Crowned monogram formed by the letters CAR. Below the monogram, the number seven, in Roman numerals. The words on the obverse are carved between two pointed circles. The division between the words appears to be a four-petaled flower.

Front Speech: Charles VII, by the grace of God...

Back:

Words on the back: NAVARRE+REX+1789

Description of the Reverse: The crowned coat of arms of Navarre between the letters P and A. These letters are the hallmark of the Pamplona mint on coins minted during the 18th century. The words on the reverse are engraved between two pointed circles. The division between the words appears to be a four-petaled flower. Finally, the year of minting, 1789.

Backstage Talk: King of Navarre

On June 8th, the auction of the magnificent collection of Navarrese coins by Alvarez de Toledo took place at a well-known auction house in Madrid. This collection included excellent coin specimens and, as a result, attracted a large number of spectators and participants.

Money flowed in droves, with a few pieces reaching the 5,000 euro mark, but overall I thought the auction prices for the pieces were quite high.

I myself also met there, at the time and day mentioned via the internet. The issues I had in mind or aimed for were very modest. On the one hand The Berdabio bertsolarist I had in mind a 1748 Maravedi of Fernando II, which is included in the price. I had a limited budget and the price was rising, so I immediately realized that I would have to pass on this one.

The second objective was the maravedia of Charles VII of Navarre, the title and photo of this entry. In this case, although in my opinion I paid more than I should have for the piece, I stayed within the budget. I was completely delighted, although I probably made a bad investment. It is known that in this area professional dealers and especially auction houses do business, fans are fans and we take pleasure in our great and small joys.

This is not the first time I have been on the trail of the 1789 maravedi of Charles VII. In July 2020, I acquired another copy at an auction house in Barcelona. However, during the mailing, someone read the name of the auction house, the Latin word for gold, on the cover of the letter, and thinking that they had acquired a great treasure, cut the cover and stole the coin. I wonder where it is now, this copy that I show below, somewhere on the postal route between Barcelona and Germany!

Image of the maravedia of Charles VII stolen in July 2020 – 3.03 gr

I was particularly looking forward to this issue, but not just because it was released a year ago, because in my opinion it is a very significant issue in the history of Basque coinage. Here are some brief reasons to support the above:

First of all, it is the only copy made under the name of Charles VII (reigned from December 1788 to March 1808) King of Navarre; it records the year 1789. It is clear that this year marked the beginning of the political and ideological transformation initiated by the French Revolution, which would have profound consequences for Navarre and the entire Basque Country.

The instability and wars caused by the French Revolution stopped the minting of Navarre coins for 29 years, until they were resumed in 1818 during the reign of Fernando III, son of Carlos VII. However, the minting that began 29 years later was based on completely changed patterns. As a result, we have the last minting of the Marabedi-Kornado system used in the 18th century.

This series of coins was the last type of coin minted at the headquarters of the Chamber of Accounts of Navarre. The headquarters of the Chamber of Accounts of Navarre has survived to this day and can be seen at number 10, Florencio Ansoleaga Street, Pamplona.

The facade of the old Gothic mint at 10 Florencio Ansoleaga Street – Eaeaea – Wikipedia Commons

King Charles IV of Navarre (Charles V of Germany) bought the building and converted it into a mint and treasury in 1524, and from then on, the minting of coins in Upper Navarre was carried out there until the last coins arrived in 1789. The Treasury still survived in the same location until 1836, but the Navarrese coins minted between 1818 and 1837 were no longer minted in this building.

The interior garden of the former mint and treasury – Josu Goñi Etxabe – Wikipedia Commons

And finally, these coins They are the last coins struck by hammer in the Kingdom of Navarre, the Basque Country, the Iberian Peninsula and probably all of Western Europe.. They therefore have sufficient significance, even though they are very modest coins in terms of size, weight and images. More Navarrese coins were minted after 1818, but the coins minted during the reign of Fernando III are already The flywheel press on display at the Museum of Navarre were worked through.

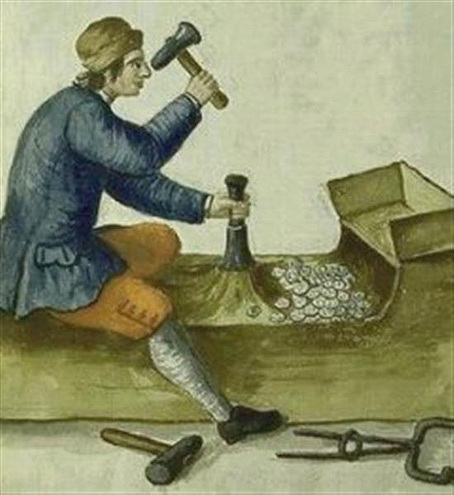

Image showing coinage struck by hammer in the 17th or 18th centuries

According to the hammer coinage technique, a previously created coin or coinage was struck between a fixed die (called a pile) attached to a fixed base and a movable die held by the coiner with his hand or by a crowbar, thanks to a powerful blow given by a hammer. Both the pile and the images carved on the die were represented on both sides of the coin due to the powerful blow of the hammer.

Few examples of the dies and piles used in ancient hammered coins have survived to our times. But in this respect we are extremely fortunate in the case of the Pamplona Mint, as the Museum of Navarre preserves in its archives various machines, tools, and dies and piles used in the mint of the capital of Navarre between the 16th and 19th centuries.

Not only in the deposits, the Museums of Navarre from May 2021 A new room dedicated to the coinage of Navarre opens because it has, showing a selection of around 200 copies in its treasures; after a gap of thirty years, it is finally here.

Very few examples of fixed dies or piles have come down to us from the collection of the Museum of Navarre, only five examples to be precise, and of these five we do not have any that correspond to the coin of today's entry. However, in the case of the movable dies, we have come down to us just over twenty examples corresponding to the coinage of 1789. All of these examples can be found in the book “La colección de útiles de acuñación del Museo de Navarra”, published in 2003. I highly recommend this book, it is a very useful daily reference tool for the study of Navarre coinage.

Even without purchasing the book, you can consult most of the exhibits kept by the Museum of Navarre through the CERES digital platform. As an example, here is a die from the back of the coin we are studying today:

Top of the movable die of the maravedi coin of Charles VII of 1789 – Photo taken from the CERES platform – Article list number 20,301 – Book die 301

View from the side of the movable die of the maravedi coin of Charles VII of 1789 – Photo taken from the CERES platform – Article list number 20,301 – Book die 301

The two previous photos show one of the 1789 coin dies kept in the museum. The deformation caused by the hammer blows on the die can be clearly seen. If we look at the weight and dimensions of the movable die, we can see the following:

Die made of cast iron;

Height = 35 mm; Width = 25 mm; Diameter = 23 mm; Weight = 148.20 gr

Considering that the average diameter of the coins is 19 millimeters (and that they are also octagonal in shape), we will notice that the dies have a diameter of 23 millimeters. Consequently, it is completely understandable that all these maravedi coins have reached our days with incomplete inscriptions. This is because they were created in this way during the minting period, and the long years of use did not help to preserve specimens with a beautiful appearance and as complete an inscription as possible. If we want to get an idea of the general appearance of the coins, we will have to start with the study of the preserved dies or with the analysis of numerous specimens.

In general, the workmanship of these coins was very simple in their time and, given their long use over many years, most of the specimens have survived to our days in a relatively poor state of preservation.

Two 1789 maravedi coins next to each other – The left side of the textuidations can be seen on the first one

If we examine the fixed die or pile of the obverse of the coin, we have already said that no pile specimen corresponding to the coin of 1789 has come down to us. However, in the early years of the reign of Charles VI (1759-1788), father of Charles VII, what is called the obverse of the maravedis was printed using a movable die, and fortunately, several specimens of these movable dies have come down to us.

These movable dies of Charles VI allow us to clearly compare the images and pictorial texts that appear on the coins of his son. The design on the obverse of Charles VII's coins follows the model of his father, where the Roman numeral VI was replaced by the Roman numeral VII, corresponding to his son.

The top of the movable die from the early days of the maravedi coins of Charles VI – Photo taken from the CERES platform – Article list number 20,243 – Book die 243

View from the side of the movable die from the early days of the maravedi coins of Charles VI – Photo taken from the CERES platform – Article list number 20,243 – Book die 243

Die made of cast iron;

Height = 52 mm; Width = 28 mm; Diameter = 23 mm; Weight = 272.30 gr

And finally, what was the weight and law of these coins? And how many pieces were minted? The simplest answer is related to the law. The billon coins of the Navarrese period lost the little silver they contained after 1604; as a result, these maravedas were made of pure copper.

Regarding the weight and quantity data, we know that these maravedi coins were minted in response to a royal request made at the meeting of the Navarrese courts between 1780 and 1781. On April 24, 1781, the king authorized the minting of 12,000 ducats of maravedi and 4,000 ducats of cornado.

The royal authorization allowed the minting of 122 maravedi coins for each Navarrese pound. With these data we can find the nominal weight of the maravedi coins, that is, if each Navarrese pound was equivalent to 371 grams, this would be 371 grams per coin / 122 coins = 3.04 grams It would give us an average value. We do not have data on the remedy or weight tolerance allowed by the permit, but most specimens are between 2.65 grams and 3.35 grams.

Regarding the quantity minted, the royal authorization of 1781 authorized the minting of 12,000 ducats of maravedi. According to the coinage values in force in Navarre at the end of the 18th century, each ducat was worth 392 maravedi. A simple calculation will show that authorization was granted to mint 4,704,000 maravedi.

|

Pound |

Real |

Card |

Gros |

Maravedia |

Cornavin |

|

|

Ducat |

6 and 8/15 |

10 and 8/9 |

49 |

65 and 1/3 |

392 |

784 |

|

Navarrese Peso |

4 and 4/5 |

8 |

36 |

48 |

288 |

576 |

|

Navarrese Libera |

1 and 2/3 |

7 and 1/2 |

10 |

60 |

120 |

|

|

Royal Navarre |

4 and 1/2 |

6 |

36 |

72 |

||

|

Card |

1 and 1/3 |

8 |

16 |

|||

|

Gros |

6 |

12 |

||||

|

Navarrese Marabedia |

2 |

Coin equivalents used in the Kingdom of Navarre at the end of the 18th century

The number of pieces of just over four and a half million seems quite large for the Pamplona mint. The minting of this entire amount was not tied to a single year, but was a quantity that had to be minted over several years. However, between the authorization of 1781 and the appearance of the maravedi of Charles VII in 1789, we only know of the maravedi of 1782, 1783 and 1784.

It is difficult to believe that the total number of coins authorized, just over four and a half million maravedis, was ever minted. However, in 1795, the courts, faced with a shortage of copper coins, requested the minting of another 20,000 ducats of maravedis (as well as another 10,000 ducats in cornados). The instability and wars brought about by the French Revolution had significantly increased the price of copper. This made it impossible to mint any more coins, especially given the profitability problems that the proposed ratio of 122 coins per pound offered.

Considering the number of over twenty dies that have survived to our days, I would probably place the number of maravedis minted in 1789 at between 450,000 and a million. We can explain this operation by the following factors: on the one hand, it is likely that not all the dies used in the minting have survived and, secondly, given the modest quality of the specimens, we estimate that each die was used to mint an average of 15,000 specimens.

A document written by the mint managers in 1728 states that each hammer worker produced 16,000 coins per day. It also states that before it was exhausted, each stack was used to produce about 40,000 coins and that three movable dies were used for each stack. That is, each movable die was used to produce an average of 13,333 coins.

During the reign of Philip VII (1700-1746), the year the document was written, 16,000 maravedia – 2.68 gr – were minted every day by an official hammerer, who received a daily salary of 4 reales.

During the reign of Philip VII (1700-1746), the year the document was written, 16,000 maravedia – 2.68 gr – were minted every day by an official hammerer, who received a daily salary of 4 reales.

On the other hand, it is quite difficult for me to imagine that the Pamplona mint could have minted more than a million maravedis in a year, as it was a small and outdated mint for those times in 1789.

GENERAL CATALOGUE OF THE NAVARRE COIN – Ricardo Ros Arrogante – 2013 – Altaffaylla Publishing House

MONETARY POLICY IN THE KINGDOM OF NAVARRA AT THE END OF THE ANCIENT REGIME (1747-1838) - Mikel Sorauren - link

THE COIN IN NAVARRA – NAVARRA MUSEUM – EXPOSITION FROM MAY 31 TO NOV 25 2001. Miguel Ibáñez Artica link

NAVARRE COINS AND ITS DOCUMENTATION (1513-1838) – 1975 – Jorge Marín de la Salud

Paridades de la Moneda Navarre, from the end of the 18th century until the creation of the peseta - Jordi Ventura and Subirats 1986 - link

The Museum of Navarre has inaugurated a room with one of the world's most important numismatic collections – Nafarroa.eus 2021- link

The collection of minting tools of the Museum of Navarra – Miguel Ibañez Artica, M. Ines Tabar Sarrias, Alicia Irurzun Santa Quiteria, Ma Dolores Ibañez San Millan, Julio Torres Lazaro 2003

The Navarre currency in the 18th century – Pedro Damian Cano Borrego – Hecate Aldizkaria 2018 – link

All personal data collected on this blog will only be used to disseminate the contents of this blog. Personal data will never be transferred or sold to third parties. You can unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the link in the footer of our emails.

Pingback: The only marauder of Charles VII – The Last Hammer Dance • RIGHT

Great entry!!! I haven't read it. I liked it a lot. Great work!!!

Greetings from Pamplona.