Among the objects presented by the Basque Museum of Bayonne are five standard weights from this city. These weights were placed in the town hall in 1788 with the intention of being used as standard weights. They have a cylindrical shape and are pierced at the top by a hole through which a movable ring can be placed. The faces of the cylinder depict the image of the coat of arms of the city of Bayonne.

Weight Patterns kept in the Basque Museum of Bayonne – Courtesy of the Basque Museum of Bayonne

The weight standards were made in Paris by order of the councilor Dominique Dubrocq in 1787, and a year later, in 1788, at the request of the Bayonne Chamber of Commerce, Michel Sieur, the engraver of the Bayonne mint, changed their weight. Why this change in weight?

Today, we are accustomed to the decimal metric system in a large part of the world, but this system based on grams and kilograms was first adopted by the French revolutionaries on April 7, 1795. Until then, each region had its own specific weight standards, all more or less the heirs of the Roman pound, but which accumulated numerous differences throughout history.

These differences were reflected in the different weight standards that could be found in the Basque territories. Álava used the Castilian pound and its value of 460.100 grams as a standard. Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa were also part of the Castilian crown, and therefore the Castilian pound and its value of 460.100 grams should have been used as a standard weight. But instead, Bizkaia had pound weights of 488 and Gipuzkoa of 492 grams. The Bayonne pound had 490.7009 grams, and that of Navarre 372 grams. But while the Bizkaia, Gipuzkoa and Bayonne pounds were subdivided into 16 ounces, the Navarrese pound was subdivided into 12 ounces. Therefore, in most Basque territories an ounce had a value between 30.5 and 31 grams, while in the kingdom of Castile it had a value of 28.8 grams. It is clear that the trade relations between the Basque regions led to a certain unification of weights and that this unification occurred around the value of the Troyes or Paris pound of 489.5058 grams (except in the case of Álava).

Therefore, this adjustment of the Bayonne standard weights in 1788 was made with the intention of unifying the Bayonne weights with the Paris pound, that is, the weights kept in the Basque Museum went from 490.7009 gr/pound to 489.5058 gr/pound.

The 1, 2, 3 and 25 livres were lost in the fire at Bayonne town hall on December 31, 1889; the 4, 5, 10, 50 and 100 livres (although the 10 and 50 livres lost their ring) are on display at the Basque Museum in Bayonne.

This look at weight references will be useful when we discuss monetary weights. Since ancient times, rulers granted their mints the right to mint money, always according to strict reference standards. They established through monetary ordinances the number of coins to be produced in a mass of metal, and the unit of measure for this mass of metal was usually the mark (the mark was itself half a pound, except in the Kingdom of Navarre).

For example, the first coinage ordinance issued in 1481 during the reign of King Francisco Febo of Navarre states the following (translated into Basque from the Navarrese romance of the time):

"Martin de Aoiz, a well-known merchant, was responsible for the minting of the new coins. The highest value piece, the silver gros, had a silver law of 4 dinars and 3 grains, that is, a silver legality of % 34.37. A mintage of 88 pieces per metal alloy mark was established, that is, each coin had an average weight of 2.78 grams. The permitted remedy or margin of error was 3 grains in the silver law, and one piece per mark in relation to the number of coins."

The value of the silver mark used in the Kingdom of Navarre was around the 244.75 gram mark of Troyes or Paris; it was called the Pamplona mark and weighed around 248 grams. After the conquest of King Fernando, the mark that appeared in the coinage ordinances of 1513 was the Pamplona mark and while a Castilian mark was worth 67 reales, a Pamplona mark was worth 72 reales. In two cases, reales of around 3.44 grams were minted and in two cases a legality or law of 11 dinars and 4 granas was used.

As for the northern mints, both the Bayonne, Donapaleu and Bearn mints used the Troyes or Paris mark as a reference. Therefore, when reading the coinage ordinances, we must be very careful about the units that appear there. For example, in the early Middle Ages, it was quite normal in most of the coinage ordinances of Western Europe to use the weight of the mark of the German city of Cologne and in this case we are faced with 233.856 grams.

As for silver coins, the silver law was expressed in money and grains. Pure silver had a law of 12 money and each money was subdivided into 24 grains, that is, pure silver had 288 grains. In the case of gold, pure gold was 24 carats and each carat had 4 grains. The aforementioned gros coins of 1481 had a silver law or legitimacy of four money and three grains, that is, (4/12 + 3/288) * 1000 = 343.75 thousandths.

Regarding the weight tolerance, the ordinance allowed a tolerance of one coin per mark weight, that is, it allowed the minting of between 87 and 89 pieces per mark. This would give us a weight tolerance of between 2.813 and 2.75 grams, around the nominal weight of the coin of 2.78 grams. This is not a large tolerance, but this does not mean that each coin was weighed, especially in the High Middle Ages (except in the case of gold coins). In general, all the coins minted in those times were put into a box and a general weighing and counting was carried out with selected batches of coins. However, at the end of the Middle Ages, especially at the end of the 15th century and the beginning of the 16th century, the minting of larger silver coins began to prevail and as a result, more stringent control elements began to be used. From this moment on, weight controls began to be established for individual coins.

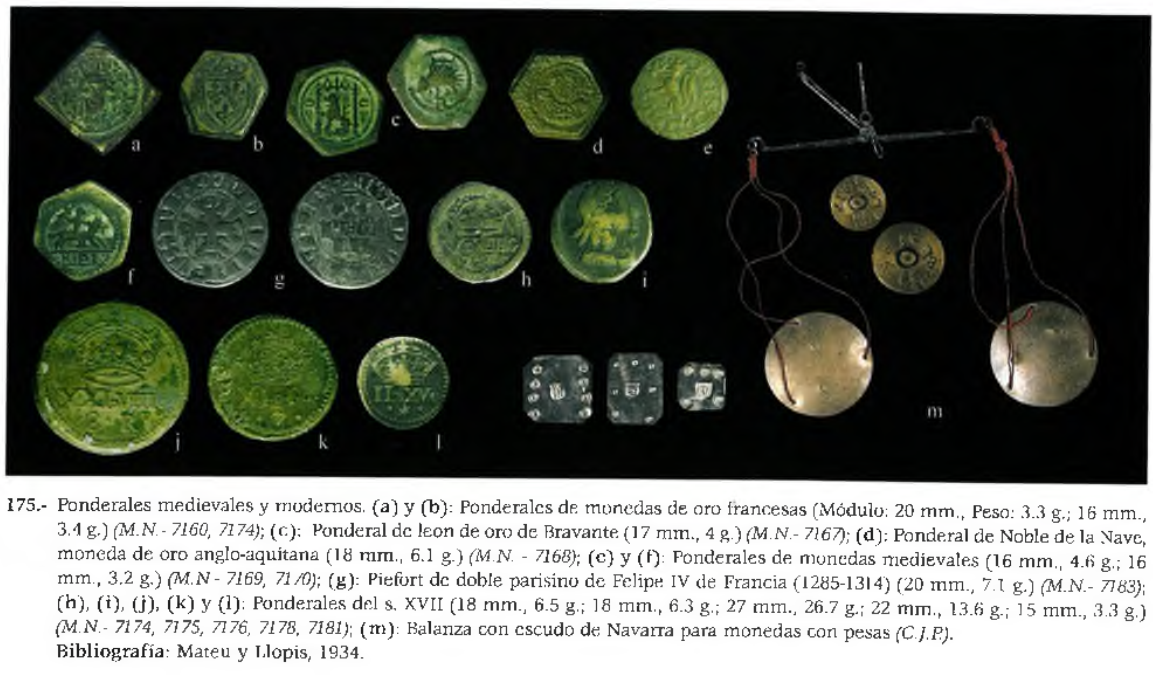

The weight of a coin did not correspond to a round value and the use of different standard weights would be necessary to verify the weight of each coin. In order to avoid this cumbersome use, reference weights, called denerals or ponderals, were created for use in the coinage process. Each weighed the exact mass of a well-defined coin and were distinguished from each other by distinctive marks.

The minting of coins, which established standard weights of money, was highly regulated, but it was not the privilege of the sworn mint masters and their assistants who signed their weights.

Depending on where the money was produced, the coins could be made of copper, bronze, crystal or brass, and in terms of shape they could be round, square, rectangular, hexagonal, octagonal or sometimes trapezoidal.

On the one hand, they bore the design of the coin they represented, sometimes accompanied by the full name or abbreviation. In some cases, the design was accompanied by the initials of the sovereign ruler.

On the other side, the symbol and weight surrounded by the engraver's initials usually appeared.

Brass ponderal teston engraved in the name of Louis XII (1498-1515) – 9.45 gr – The reverse shows the engraver's symbol, and the nominal weight of the coin VII DXG, which is seven dinars and ten grains – cgb Auction House

The references to money and grain in this generalization are not indicative of the silver law, but rather units of mass. In the Kingdom of France, each pound (489.5058g) was subdivided into two marks (244.75g), each mark into eight ounces (30.59g), each ounce into eight gros (3.82g), each gros into three dimes (1.27g), and each dime into 24 grains (0.053g). The names of many medieval coins can be found in references to these units of mass.

As a result, the back of this coin shows a mass value of 489.5058gr*(7/384)+ 489.5058gr*(10/9216)=9.45gr, the same weight as the grain.

18th century 4 reales deneal from the Kingdom of Castile – 13.60gr – X of XVI gr – 4R

As we have seen, a small deviation was allowed regarding the nominal weight of the coin and the metal law, which, among other things, was called remedy, permission or tolerance.

These weight tolerances were called forte or feeble, distinguishing whether the error was excessive or insignificant. Heavy coins (forte) reduced the carving, while feeble coins led to an increase in the carving, that is, in addition to the maximum number of pieces that could be struck from a frame, one (or more) piece could be left over.

For this reason, the mint master created these small weighing scales called denerals or ponderals, similar to those used in assays, so that the relevant worker could verify the unit weight of each coin. The denerals also came in three different series, nominal, strong and weak, so that the coin remained within the authorized weight limits.

The collection of Ponderals featured in the book of the exhibition La Moneda en Navarra, 2001

Essentially, the exchange value of a coin, outside the kingdom where it was minted, depended on its mass and its law or legitimacy (after all, the law and mass determined the amount of gold or silver contained in the coin). The mass or weight, however, could easily be changed by abrasion (a consequence of the wear and tear of the coin caused by circulation) or by the practice of minting (fraudulent work, cutting the edges of the coin in order to recover some of the metal).

Ultimately, both when authorities collected their taxes, when merchants received payment for their goods, and when money changers exchanged money between different territories and kingdoms, everyone needed references to weights and currencies, and also, to the extent possible, the means to verify the legality of coins.

We will discuss the means of finding the law of coins in another article, but the general tool for determining the weight or mass of coins was the balance or precision scale. It became an everyday tool for money changers and merchants in the Middle Ages and early modern period. And the boxes of these scales often contained ponderal or denarius coins.

A 16th century money scale showing denominations from different kingdoms – cgb auction house

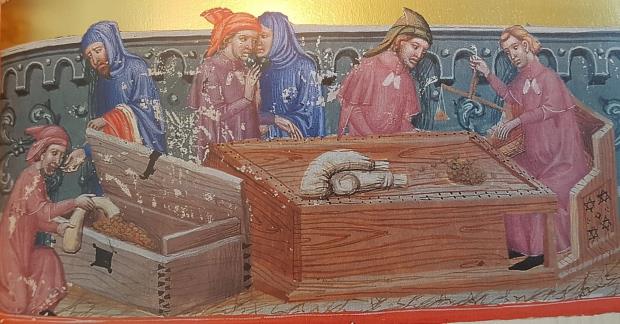

Illustration showing the weighing of gold coins using a triangular plate scale 1333-1348 – Ferrer Bassa Workshop – National Library of France

In the 17th and 18th centuries, in order to prevent counterfeiting, coins were marked with engraved edges. This allowed anyone to immediately notice the counterfeiting operation by observing and noting the intact or damaged edge of the coin.

These improvements in the coin manufacturing process gradually made the practice of weighing coins obsolete, and the art of coin balances disappeared completely by the middle of the 19th century.

Bibliography:

LES POIDS MONETAIRES DU MUSEE – Basque Museum of Bayonne – link

Los antiguos pesos y medidas Guipuzcoanos – Ignacio Carrión Arregui 1996 – link

THE COIN IN NAVARRA – NAVARRA MUSEUM – EXPOSITION FROM MAY 31 TO NOV 25 2001. Miguel Ibáñez Artica link

The correct weight of coins, a matter of public order – Albert Estrada-Rius – link

Les Poids Monetaires Un Peu D'histoire – Les poids Monetaires Blog – link

Lordship and monetary production in the kingdom of Navarre at the end of the 15th century (1481-1495) - Juan Carrasco - link

NAVARRE COINS AND ITS DOCUMENTATION (1513-1838) – 1975 – Jorge Marín de la Salud

Pesos and laws in the coins of the Middle Ages and the Modern Age – Adolfo Ruiz Calleja's blognumismatico.com blog – link

All personal data collected on this blog will only be used to disseminate the contents of this blog. Personal data will never be transferred or sold to third parties. You can unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the link in the footer of our emails.

Pingback: Sancho Iturbide's Carlins of Navarre | History of Basque Coinage

Pingback: Paulo Girardi and his Navarrese Currency Report | History of Basque Coinage

Pingback: Silver Shields of Louis II | History of Basque Coinage

Pingback: The Last Nine Coins of Donapaleu | History of Basque Coinage