“Navarre shall be the wonder of the world”… these are the words put into the mouth of King Ferdinand of Navarre by the English writer Shakespeare in the play “Love's Lavour's Lost”. This play was written in the mid-1590s, and although Shakespeare named the King of Navarre Ferdinand, the Navarre mentioned in it is the Kingdom of Navarre, consisting of Lower Navarre and Bearn, around the end of the 16th century under Henry III. It is noteworthy, however, that Shakespeare named the King of Navarre Ferdinand… again with a touch of humor or irony.

In any case, and although there are some exceptions, the Kingdom of Navarre in the 16th century did not become a wonder of the world, at least not in most of the social, economic, scientific or political areas that are usually a reference. However, in one area, it was a world reference from the middle of the 16th century to the beginning of the 17th century, and this area was that of coinage. Let's delve deeper into this history.

As we saw in the section on the dowries of Henry II (link), Queen Joan III's father, Henri de la Courcelles, brought Jean Erondelle to Pau in 1554, with the intention of setting up a state-of-the-art mint in the tower house next to the castle. But who was this Jean Erondelle?

Hernicus II of France (not to be confused with the one of Navarre) founded a mint called the Moulin des Ètuves in Paris around 1551. This mint was to use the new medal presses invented by the Swiss silversmith Marx Schwab in Augsburg around 1550. The aim was to use new coinage practices that guaranteed the quality, legitimacy and integrity of the coins against edge cutting.

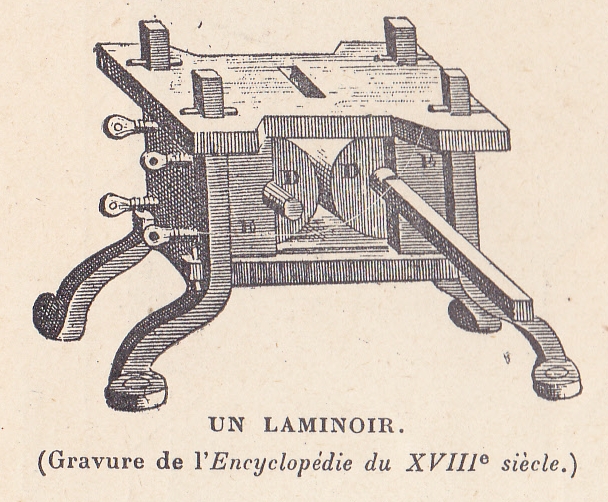

In order to improve the quality of the coins (as its name suggests, the word moulin means mill), parallel rollers powered by water worked as metal laminators, through which smooth, fine and precise metal sheets were created. The hot metal sheets were passed through the rollers several times, until they achieved the desired smoothness, quality and thickness. If you want to get an idea of the use of laminators powered by water mills, the following video is relevant link.

Image of a laminator as depicted in the 18th-century encyclopedia of Diderot and d'Alembert

This video shows the operation of the laminators of the Royal Mint of Segovia, which was founded at the end of the 16th century. The laminators used in the Pau Mint were similar to those shown in the video, but while in Segovia the coinage was done by roller, in the mint of the Kingdom of Navarre in Pau the coinage was done in a different way, by means of a flywheel press.

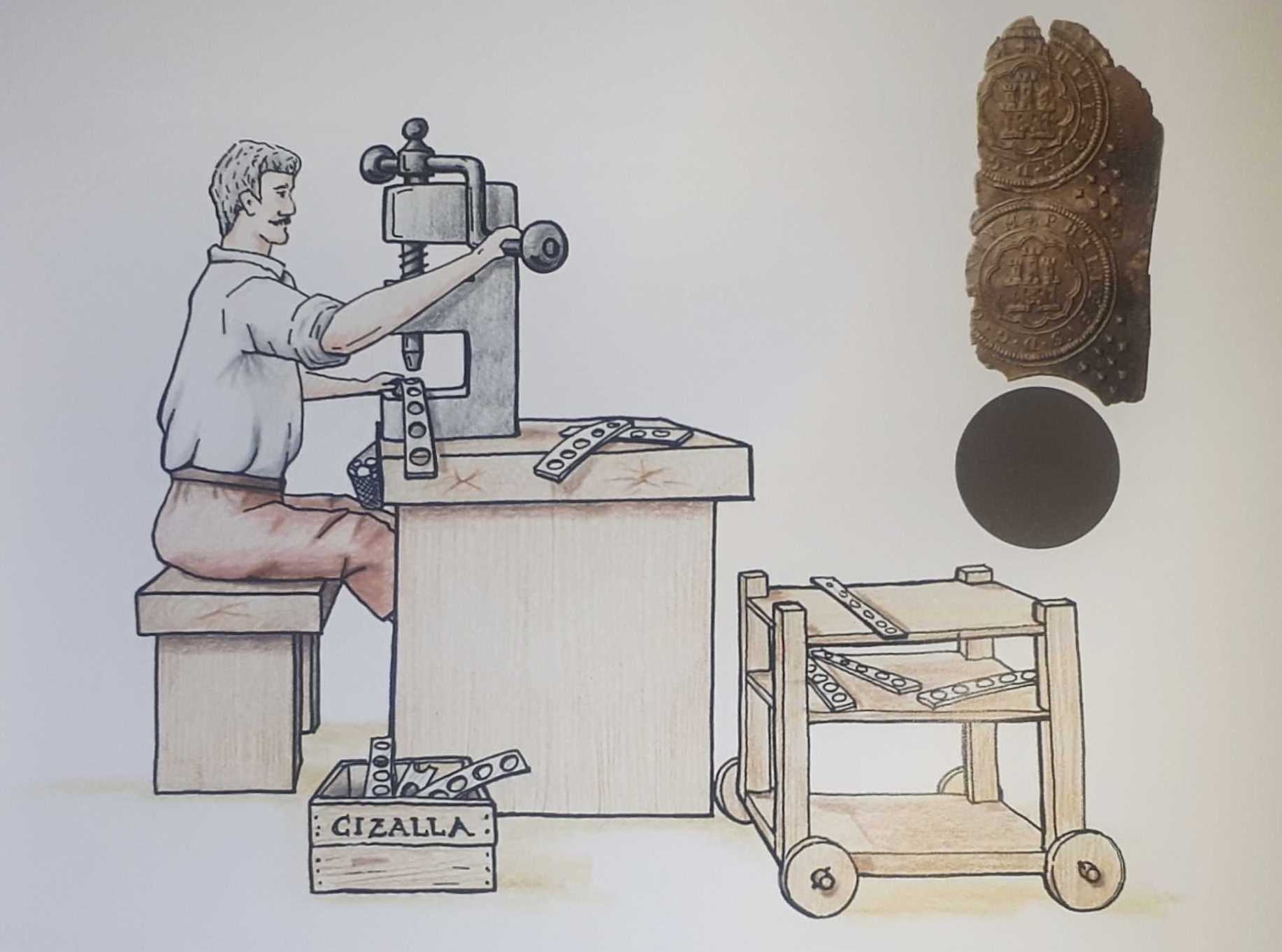

These metal sheets produced by laminators were converted into circular billets or coins by cutting machines. Once the sheets were cut and the edges of the billets or coins were smoothed, the process of weight control and, if necessary, weight adjustment or adjustment was carried out.

Image showing the creation of coins or coins from metal sheets using cutting machines

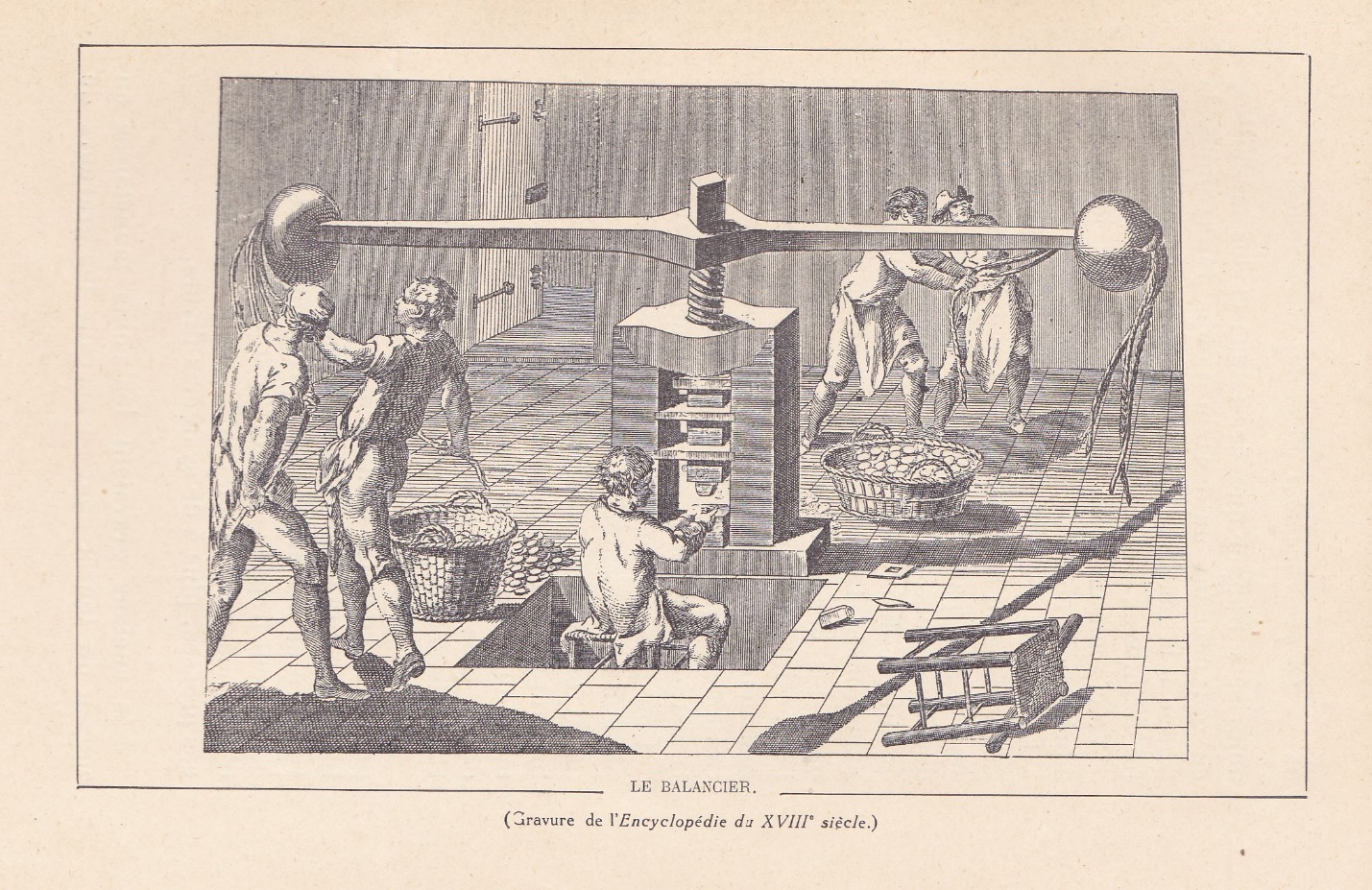

And finally, these coinages were processed into round, precise and beautiful coins using new flywheel presses. If you want to get an idea of the use of these flywheel presses, the following other video is also relevant link

Image of a wheel press as depicted in the 18th-century encyclopedia of Diderot and d'Alembert

Large flywheel presses could have crews of eight or twelve workers. In order to reach the required strike pressures for the machine, these workers would exert a strong force on the flywheel using ropes. The horizontal shaft of the flywheel had additional weights at the ends, in order to increase the force of the strike through inertia. It was hard and difficult work, with crews changing every quarter of an hour, so that they could take a short break and continue the coining work with quality. It was also a dangerous job for the seated worker, who had to insert the dies and extract the coined coin. He had to be completely synchronized with his crew during the insertion and withdrawal operations, otherwise he risked losing his fingers or hand (since accidents, due to long working hours, occurred more frequently than desired). Through this process, a maximum production of about twenty coins could be achieved per minute. In this section, of course, we have only talked about the mechanical coining processes, without going into the necessary metallurgical casting or chemical processes.

In summary, the Moulin des Étuves mint was the birthplace of the modern coinage process. Before the opening of the Moulin des Étuves mint, coins were struck by hammer in most parts of the world, including the mints of France, Navarre, and Spain. This innovative process completely opposed the other French mints that struck coins by hammer, including the other mints in Paris, and as a result, in 1558, the Moulin des Étuves was eliminated from the minting of special coins, medals, and tokens.

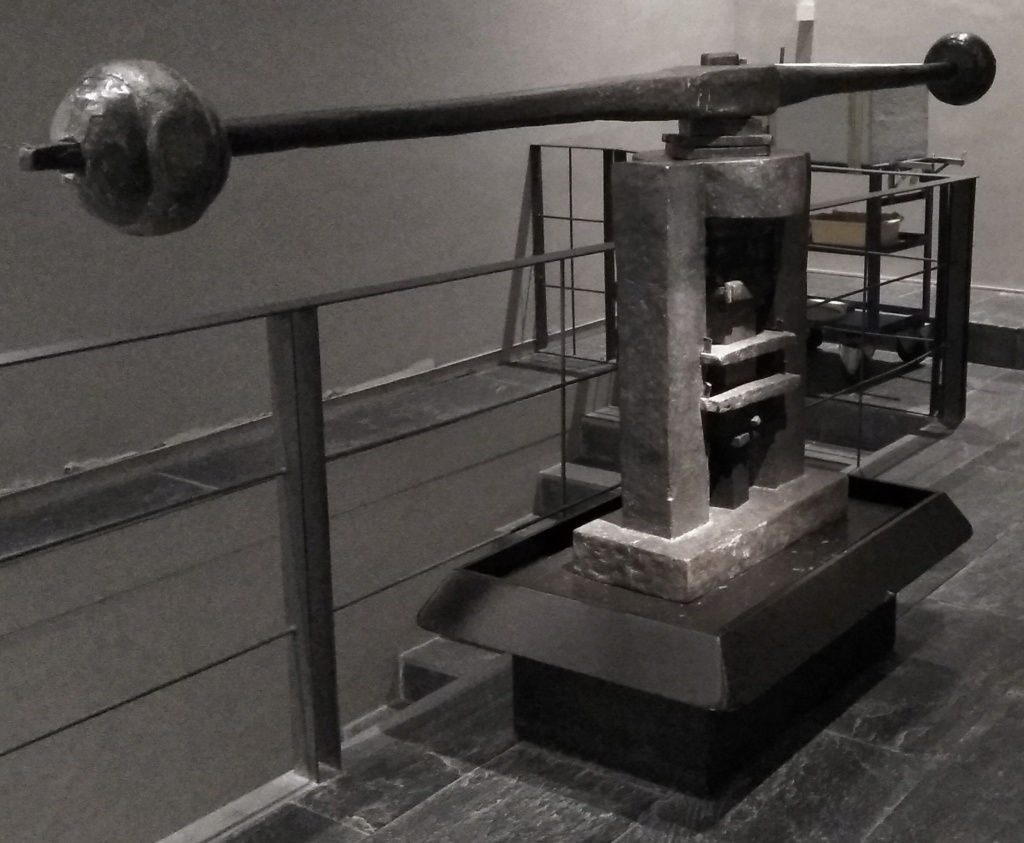

A wheel press from the Pamplona Mint, from the late 18th or early 19th century, now housed in the Museum of Navarre.

But before that date, many workers had already left the Moulin des Étuves and one of those who left was Jean Erondelle. It seems that Jean Erondelle worked as an engraver from the very beginning of the Moulin des Étuves. After working at the mill mint there between 1552 and 1554, he began dealings with King Henry II of Navarre. In the same year, he left the mill mint in Paris and moved to Pau with all its secrets, in the service of the King of Navarre. In fact, and it seems that while he was already working in Paris, he was secretly replicating and improving machines, in activities that testify to the industrial espionage of the time.

Jean Erondelle minted the first Navarrese trial coins dated 1555. He was successful in his attempts and as a result laid the first foundations of the Pau mint. Among the coins produced are gold escudos, silver testons and billion douzaines.

Proof of 1555 minted at Pau mint under the command of Jean Erondell – 27mm, 9.22gr

+ ANT ET IOAN DEI G RR NA DDB – + GRATIA DEI SVMVS QD SVMVS

The mint was located in a tower house next to the royal castle of Pau. This was already working as a mill, since the millstone was moved by a canal brought from the Ousse river. It was therefore perfectly suited to the location of water-powered rolling mills. Three rolling mills were installed in the tower house, and since there was not much space left, additional buildings were erected around the tower house. These buildings housed the copper, gold and silver smelting areas, the minting workshop with three flywheel presses, the exchange office, the officers' residences, the coin testing and fitting workshops, and the material or product input and output sections.

The three laminators brought by Jean Erondelle were located here, driven by the force of the canal that can be seen at the foot (the royal castle of Pau in the background) – Wikipedia image

But Erondelle was an engraver and he probably had more problems than the number of trials when it came to converting the coin mill into a solid and reliable coin production plant. And to be able to take this second step, he had to enlist the help of Etienne Bergeron.

Etienne Bergeron was mintmaster of the Moulin de Étuves between 1553 and 1558, during which time he greatly improved the efficiency and productivity of the new mint.

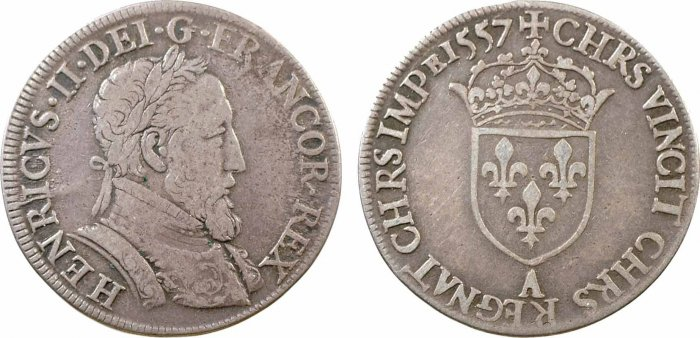

Testicle of King Henry II of France, carved under the direction of Etienne Bergeron – Moulin des Étuves – 1557 – 28.0mm 9.30 gr

The EB Monogram, characteristic of Etienne, can be seen in front of the date 1557.

These improvements brought him the anger and hostility of other mints that used hammer coinage techniques, and as a result he left his position and moved to Nancy, which was abroad at the time, with the intention of continuing to work on mechanical coinage under the command of the local Duke of Lorraine.

Etienne Bergeron was of the Protestant faith and, apparently, around 1561, he gladly accepted an offer of work from the engraver Jean Erondelle and Queen Joan. He left Nancy and went to work as a mintmaster in Pau.

A coinage trial that may reflect this trajectory was announced in December 2023. This coinage trial presents the same pattern as the Pau testons, but on the obverse, instead of the Albret motto and coat of arms of the Pau testons, it features the coat of arms and motto of the testons of the Duke of Lorraine! The origin of this Piedfort coin is unknown and we have no documents about it. The obverse dies seem to have been used between 1567 and 1569, while the obverse dies seem to have been used between 1560 and 1574, as the mintmark B can be seen. As mentioned, the connection between the two mints is Etienne Bergeron. But at the same time, the Cardinal of Lorraine was one of the leaders of the Catholics in France, and this coinage can be related to the short Catholic attack suffered by Bearn in 1569, during which Pau was subdued in a few weeks.

The only known proof of a test coinage struck at Joan III's Pau mill mint, perhaps between 1567 and 1569 – 29.07gr, about the weight of three test coins, 27mm diameter 6mm thick

Found: IOANNA.DGREG.NAVAR.DB(Beef) P – Portrait of Joanna, Queen of the Testimonies

Obverse: MONETA.NOVA.NANCEI.CVSA. – Obverse of the coins of the Duke of Lorraine showing the city of Nancy in Lorraine

Heritage Auctions, Weekly Auction 232349, Lot 61214 8.12.2023

In the accounts written by Etienne, the denominations used to make repairs to the mint machines are listed. In these accounts, he shows that the innovations in the flywheel presses were made of Basque steel (acier Basque, probably Gipuzkoan or Bizkaian), one of the most precious European steels of the time.

Etienne attracted more talented people to his project. Guillaume Martin, an engraver based in Paris, collaborated with Etienne on several projects around 1557-1558, but in the latter year he lost the competition for the position of engraver-general of the kingdom of France to Claude de Héry.

GuilMedal commemorating the marriage of Francis II, Dauphin of France, and Mary, Queen of Scots, attributed to Laume Martin – made in 1558, this copy is a 19th century replica

Guillaume maintained close relations with Etienne and, after the disappearance of Jean Erondelle, appears in possession of the post of engraver-general of the kingdom of Navarre in 1564. Guillaume Martin was the creator of the images of the testons and shields of Queen Joan, which were minted at the Pau mint from 1564 onwards. The image of the star, which was her emblem, appears on these coins above the crescent symbol of Etienne Bergeron.

Gold shield of Queen Joan – Pau Mint – 1564 – 3.40gr, approx. 24.5mm

Etienne Bergeron, mintmaster (moon) – Guillaume Martin, engraver (star)

The creator of these images was Guillaume Martin, who held the position of engraver-general of the kingdom of Navarre. However, the person who lived in Paris and worked as an engraver at the mint of Pau during his daily work was Pierre Brucher (Graveur Particulier). It is very likely that Pierre Brucher was related to the engravers Guy Brucher (1553-1557) and Antoine Brucher (1557-1568) of the Moulin des Étuves. Pierre was responsible for representing Guillaume's designs on the dies of the day and for ensuring the quality of the images on the coins produced by these dies.

This trio worked together until 1570 (Etienne and Pierre continued until 1572, but Guillaume was replaced by Jerome Lenormant) and their work marked the beginning of the golden age of the Pau mill mint. Under their command, the coins of the Queen of Navarre, minted in Pau, are considered to be the finest and most beautiful coins of the time. In the following sections, we will discuss the Pau mill coins of Joan III and Henry III.

The successive rulers of the mint maintained the quality and artistic level of coinage until King Henry III obtained the French crown in 1589. From then on, at least in my opinion, although the technical quality was maintained, the artistic level declined until around 1632, when the first closure of the Pau mill mint occurred.

It should be noted that, in the French kingdom, it was not until the 1640s that coinage using a mill and a flywheel press was introduced under the direction of Jean Warin. The mints of Bayonne and Donapaleu were among the last to abandon hammer coinage, in 1650. In the Spanish kingdoms, however, it was not until the 18th century that the use of flywheel presses was seen, although roller coinage had already been in use in Segovia since the end of the 16th century. The mint of Pamplona received its first flywheel press in 1818.

The first golden age of the Pau mint ended in 1632. Flour was once again produced in the mill of the Pau mint-tower until it resumed operations in 1650 with new machinery brought from Paris.

Bibliography:

LOVE'S LAVOUR'S LOST – Shakespeare – Wikipedia – link

TESTON MONNAIE – Wikipedia – link

FRAPPE AU BALANCIER – Wikipedia – link

Numismatique, la frappe au balancier– Youtube Video – link

Photos: Prensa de acuñacion ceca Pamplona – Reverso12 – Foro imperio numismático – link

Laminadores Real Casa de Moneda de Segovia– Youtube Video – link

Collection of costumes in the Real Ingenio - Real house of the Mint of Segovia - link

THE COIN IN NAVARRA – NAVARRA MUSEUM – EXPOSITION FROM MAY 31 TO NOV 25 2001. Miguel Ibáñez Artica link

MINT OF NAVARRE AND BEARN – WIKIPEDIA – link

HISTOIRE MONETAIRE DU BEARN – Jules Adrien Blanchet – 1893 – link

MONNAIES DE FRANCE, DE NAVARRE ET DU BÈARN – Jean Claude Ungar – 2010

LES MONNAIES FRANCAISES ROYALES – Tome 1 et 2 – 2° Edition -1999 -Jean Duplessy (In Memoriam 1929- 2020)

Le livre des monnaies feudales de Béarn et de Navarre – Jeanne d'Albret (seule) 1562-1572 – Club Numismatique Palois – Serge Salles – link

The book of feudal coins of Béarn and Navarre – Antoine de Bourbon and Jeanne d’Albret 1555-1562 – Club Numismatique Palois – Serge Salles – link

Les monnaies béarnaises de Louis XIV (I) – Christian Charlet – Revue numismatique, 6e série – Tome 168, année 2012 pp. 279-317 – link

All personal data collected on this blog will only be used to disseminate the contents of this blog. Personal data will never be transferred or sold to third parties. You can unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the link in the footer of our emails.

Hello

Great post!!!!. Great entry.

https://www.imperio-numismatico.com/t130717-prensa-de-acunacion-ceca-pamplona

Thank you Roberto, he included your photos in the Bibliography, allowing you to see the details of the Volante press.

———————————-

Thank you Roberto, I have included your photos in the bibliography, as they show the close-up details of the flywheel press!

Pingback: Queen Joan's Pau Coins | History of Basque Coinage

Pingback: A look at the Bayonne Mint – Part 2, The Presses at Work | History of Basque Coinage

Pingback: The Reflection of the Navarrese Problem in Coinage – Part 1 | History of Basque Coinage

Pingback: The Last Nine Coins of Donapaleu | History of Basque Coinage

Pingback: The only maravedi of Charles VII – The Last Mallet Dance | History of Basque Coinage

Pingback: The Last Nine Issues of Donapaleu • ZUZEU

Pingback: Navarre Shall Be the Wonder of the World • YOU