Victory: Ferdinand VII of Spain, Ferdinand III of Navarre. Liberal Triennial

Type: 10 Resealed Reals

Year: The year 1821 appears on the coin, between January and June 1822

Mint: Temporary Mint of Bilbao

Border: Grooved

Edge Engraving: ————–

Metal: Silver (about 917 thousandths, 11 pieces)

Diameter: 34 mm

Weight: 13.10 grams

Coinage: By Steering Wheel Press

Mintmaster: Manuel Domingo de Urquiza

Recorder: Pedro Sagau and Antonio Sagau

Front:

Front Words: FERN. 7°. POR LA G. DE DIOS Y LA CONST. 1821

Obverse Description: Bust of Ferdinand VII facing right, known as the head type. Circle of pearls and ornaments surrounding the portrait.

Frontal Speech: Ferdinand VII, by the grace of God and the Constitution… (King of Spain, as we will see in the background).

Back:

Back Words: REY DE LAS ESPAÑAS. U . Bo . G . RESELLADO 10 Rs.

Reverse Description: Within a laurel wreath tied with a cord, under a six-pointed star, the inscription of the new value of 10 billion reales after the re-stamping. Outside the laurel wreath, a reference to the Spanish monarchy. Below, the mint Bo. (Bilbao) between the letters of the assayers U. (Manuel Domingo de Urquiza) and G. (Pedro Gómez de Velasco)

Background Translation: King of Spain… Ferdinand VII, by the grace of God and the Constitution.

If we examine the Basque mints after the Middle Ages, three main names emerge: Bayonne, Pamplona and Donapaleu. If we look at the coins of the Kingdom of Navarre, we can add Pau or Morlaas to this list. Apart from Pamplona, we will not find any minting in the other capitals of the southern Basque Country until the end of the wars against Napoleon and the revolution of General Riego established the Liberal Triennium (1820-1823).

At this time and for a short period of six months, Bilbao had a permanent mint. From January 1822 to June 1822, a single coin model was minted, the reissued 10 reales of Ferdinand VII.

The original mint seems to have been located in the old part of Bilbao, in the Miserikordia house on Iturribide Street, in the same area where the Basque Museum of Bilbao is located today.

Entrance to the Basque Museum of Bilbao today – Photo by Zarateman – Wikipedia

The buildings, which housed the kilns, machines and offices, were reused as a pottery and printing school, and disappeared in 1877, when housing was built on Maria Muñoz Street, which had just opened at the time.

The machines needed for the operation of this temporary mint, as well as some of its workers, seem to have come from the Segovia mint. Likewise, the mintmasters came from the Madrid mint. It is also mentioned that silversmiths from Bilbao worked at the mint. The following list of people who worked on this coin has come down to us:

Manuel Domingo de Urquiza (Madrid Mint): Chief minter and general manager of the Bilbao Mint

Pedro Gomez de Velasco (Madrid Mint): Assistant to the Chief Engraver

Pedro Sagau (Chief Engraver of the Segovia Mint): Director of Engraving and Machinery

Antonio Sagau (Mint of Segovia): Pedro succeeded his brother in March

Francisco Arevalo (Guardian of the Madrid Mint): Judge of Weights and Supervisor of Materials

Mr. Durac (Segovia Mint): Machine assistant and responsible for working the dies

Manuel Garcia (Segovia Mint): Coin carving, weight adjustment and miscellaneous work

Isidro Prieto, (stamper at the Segovia mint): Use of the flywheel machine

Peter Aguirre: Employee

Ramon Aguirre: Employee

Antonio Genta: Responsible for the Sealed Border

Jose Yera: Sealer's assistant

Felipe Rivero: Mint Assistant

But why was this temporary mint established in Bilbao and why did it produce only one type of coin? The answer must be sought in the wars against the French revolutionaries and Napoleon, and in the deep crisis that the Spanish monarchy experienced after the return of Ferdinand VII and the revolt in the American territories.

Throughout the history of the Spanish monarchy, monetary policy was extremely detrimental to the economies of the different kingdoms. The enormous quantities of metals, gold and especially silver, brought from the Americas, due to the military, diplomatic and luxury expenses of the monarchy, were channeled and distributed throughout Europe. After the weakening of local industry and trade in the 16th and 17th centuries, the kingdom suffered a constant negative balance of payments, and the silver from the Americas ended up in the pockets of French, Flemish, German or English merchants.

The Spanish real zorzot became a global reference and standard of currency; the silver brought from America created a commercial and capitalist revolution in Europe, but in the Kingdom of Spain itself, it did not lead to the establishment of a productive economy or an expanding coin capital. The reforms of the Bourbon kings in the 18th century did not attack the essence of the problems. Therefore, the disruption of the metal supply caused by the wars that followed the French Revolution and the independence of the American territories at the end of the century, left the country's economy and its monetary system on the verge of collapse.

The French revolutionaries, or rather Napoleon, after conquering the Spanish territories in 1808, encouraged and forced the use and spread of French coins in the different Spanish territories. In this effort, they established a favorable exchange or exchange equivalence in favor of French coins. Taking advantage of this advantage, the local silver coins (still very precious throughout Europe) began to disappear on their way to France, where, after being minted, they were transformed into the new currency of the Revolution, the franc. In this part of the Pyrenees, the old livre coins of the French kings before the revolution remained.

Napoleon as Emperor (Emperor of the French Republic!) -1808 – Bayonne Mint – 5 Francs (still known to Basques as 5 livres) – 37.0 mm, 24.94 gr – 900 thousandths silver standard

The French revolutionaries, as they did in political thought, also brought about a small revolution in the field of coinage. They abandoned the libra-salary-money system that had been in place since the time of Charlemagne and established the new currency of the revolution, the Franc. The value of the coins was indicated on the coins themselves. Latin was abandoned and the texts were in French. In terms of weights and laws, they began to use the metric system, with five francs weighing 25 grams and a silver law of 900 thousandths.

The pre-revolutionary silver coinage system had the silver escudo (Ecu blanc or Ecu d'argent) as its yoke. The silver escudo was created by King Louis XIII after the monetary reform of 1641. The silver law, which remained constant throughout its history in 11 dimes, was 916.1666 thousandths (remember, the silver law was composed of 12 dimes and each dime was subdivided into 24 grains). The first nominal weight of the silver escudo was 27.450 grams, so half an escudo weighed 13.725 grams.

After the reform of 1641 and a supplementary decree of 1645, all the mints of the French kingdom abandoned the hammer minting and adopted the wheel press minting. This transformation was gradually implemented over the next decade, with Bayonne, for example, beginning to produce new types of coins in 1650 and Donapaleu and Morlaas in 1652. It should be noted that the Pau mint had been producing coins produced by the wheel for almost a century, since Henri II of Labrit, who had promoted the innovation of the mint, being one of the first European mints of this type.

The first half escudo minted at the Bayonne mint, 1650 – 31.5 mm, 13.54 gr – The first Bayonne coin minted by the Bolante Press

Although the shield maintained the silver standard, the weight experienced some fluctuations:

- 1641 and 1709 Between 1911 and 1913, the nominal weight of the silver escudo was 27.450 grams and the half escudo was 27.450 grams. 13,725 It weighed in grams.

- Between 1709 and 1726 In the 15th century, instability was prevalent due to wars and debt crises. The half-escudo had three different weights: 15.297 grams under Louis XIV and 12.237 and 11.725 grams under Louis XV. However, the number of coins minted during this period was small compared to the other two periods.

- 1726 and 1793 Between the years 1940 and 1945, stability was once again established, with the nominal weight of the shield at 29.488 grams, and that of the half shield at 29.488 grams. 14,744 It was placed in grams.

Half shield of Louis XIV from the Donapaleu mint, first period – 1657 – 31.0mm – 13.45 gr – archive of the cgb auction house

Half shield of Louis XVI from the Bayonne mint, third period – 1788 – 32.5mm – 14.65 gr

As we have seen in the previous three photographs, the half-escudos did not have a reference to the value inside the coin. Although the name of the coin was escudo, the value of the escudo was established by decree by the French monarchy, for which purpose the pound (pound)-soul-dire counting system was used. Each pound was made up of twenty souls, and each soul was made up of twelve souls. For example, when Louis XIII created it, the escudo had a value of three francs, but during the reign of Louis XVI it was already worth six francs, although during the crisis of 1720 it reached a value of nine francs.

Ordinary people perceived the value of coins according to their weight and metal law, or in other words, according to the amount of silver or gold they contained. After all, at that time, the monetary system was not fiduciary as it is today, and the value of the coin was guaranteed by the value of the metal (gold, silver, tin or copper) that the coin itself contained.

These differences in weight between the first and third periods, which we have seen earlier, facilitated the phenomenon known as Gresham's law in France during the 18th century. According to this law, inferior coins exclude superior coins. Since the shields and half-shields of the third period had a slightly greater weight (of the same silver law) than those of the first period, people accumulated their reserves in their treasuries, and continued to use the old coins of the first period in daily transactions.

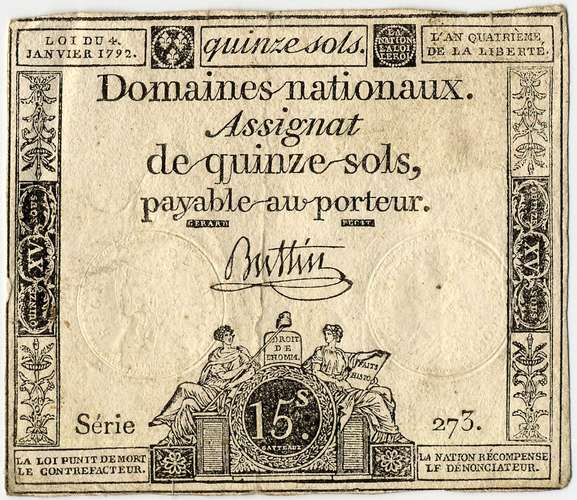

Moreover, when the French Revolution broke out, many nobles, clergy and wealthy people went abroad and took with them large treasures of gold and silver coins. During the Jacobin Terror, there was a terrible shortage of metal coins throughout the French state. The government, while issuing paper money, the “assignats”, had to put an end to the use of all kinds of obsolete and damaged coins.

Assignats or paper money created during the French Revolution – 15 sous – 1792

After the failure of paper money, the Revolution in 1795 laid the first foundations of a new monetary system called the “franc”. Later, Napoleon, in 1803, consolidated these foundations and strengthened the Germinal franc, which would become one of the most important coins of the 19th century.

But in these times, the coinage process was slow, and many years would pass before the old silver shields could be replaced. However, the French had to replace all these old coins, so how could they speed up and make this transformation cheaper? They found an excellent opportunity to carry out this transformation or replacement in an ideal parity thanks to the territories they controlled throughout Europe. And among these, thanks to the Kingdom of Spain, where in 1808, Napoleon took over the kingdom and dethroned Charles IV and Ferdinand VII.

King Joseph I and the various French authorities under him, by various decrees issued after the second half of 1808, established the equivalence of the half-escudo of three pounds at 11 reales (the reales in billions of dollars at the time) and 2 or 3 maravedis.

Was this equivalence fair? To answer this question, we will need to perform a couple of operations and, again, some equivalence analyses.

One Real of Billon = 34 maravedis

The silver real law of the reign of Joseph I and Ferdinand VII = 10 dinars and 10 grains

- (10 + 20/24) x 1000/12 = 902.777778 thousandths

The silver real coinage of the reign of Joseph I and Ferdinand VII = 170 Billion reals in each weight of the Castilian Mark.

- 230.0465 gr / 170 = 1.35321471gr weight of each billon real

How much silver was found in each billion real?

- 1.35321471 x 0.902777778 = 1.22165217 Grams

And how many French silver coins are in each half-euro?

- Between 1641-1709: 13.725 x 0.916666667 = 12.58125 Grams

12.58125gr / 1.22165217gr = 10.2985534 Billion Reals

Billion reals = 10

Marabedias = 0.2985534 x 34 = 10.150814 -> about 10 Marabedias

- Between 1726-1793: 14.744 x 0.916666667 = 13.5153333 Grams

13.5153333gr / 1.22165217gr = 11.06316 Billion Reals

Billion reals = 11

Marabedias = 0.06316 x 34 = 2.14744 -> about 2 Marabedias

Therefore, a half escudo from the third period would have a fair value of around eleven reales and two maravedis. However, a half escudo from the first period only had a fair value of ten reales and ten maravedis. But what was the average weight of the coins re-struck at the Bilbao mint?

Well, according to the documents, 2,002,462 coins were received for the re-minting work and of these, 1,970,515 were re-minted. These had a total weight of 114,641 Castilian marks and 3 ounces, which would give us an average weight of 13.38 grams per re-minted coin. If we look at the weight of the 2,002,462 coins received for the minting work, we would get an average weight of 13.43 grams. These average weights are not around the nominal weight of the third period shield or half Louis; they are much closer to the nominal weight of the first period coins.

Having established the equivalence on the basis of the weight of the coins of the third period before the revolution, we can conclude that in reality a huge number of coins of the first period or of other periods with their edges cut off were exchanged. The revolution seems to have done a great deal; on the one hand, they got rid of their old coins, without having to mint them and coin them into francs, and on the other hand, after having made a profit of about a gram of silver per coin, they brought home foreign silver, with the intention of minting it and converting it into francs.

Franc coining machine made from bronze from cannons captured from the Russians at the Battle of Austerlitz – 1807 – Paris Numismatic Museum – Napoleon ordered the creation of more flywheel machines to speed up the production of Franc coins

What was the equivalent of these three-pound coins in France? As we have seen, the five-franc coin contained 25 grams of silver, 900 thousandths of a gram. That is, each franc was worth 4.5 grams of fine silver. The three-pound half-escudo (also known as the half-louis) contained 13.5153333 grams of fine silver, so each pound was worth 4.5051 grams of fine silver. Consequently, the pound should have been worth %0.11 more than the franc, but instead it was:

- In 1796, the five-franc coin was equivalent to five livres, one sous and three francs. That is, the franc received a value %1.25 greater than the pound. The reason given was the wear and tear that Bourbon coins showed.

- In 1798, the use of francs was required for all public accounts and payments. For the time being, the use of old gold and silver coins was permitted.

- In 1803, the withdrawal of the minted and edge-cut coins was ordered. The 3-franc coins showing the image continued to be permitted to be used.

- In 1804, the use of 3-pound coins was guaranteed, but these had to clearly show the image and be newer than 1726.

- In September 1810, the 3-franc coin was set at 2.75 francs, equivalent to approximately 12.375 grams of fine silver, equivalent to a similar amount of silver in the first period half-escudos.

So it is clear that it was very profitable to accumulate all these old French coins and replace them in the Spanish kingdom with local reales. Surely, the French government itself, or the large metal dealers around the government, benefited handsomely until the war ended in 1813. When the revolutionaries withdrew, they left the Spanish kingdom without any local coins and full of old and worn-out French Bourbon coins.

When Fernando VII returned to power in 1814, he did not correct the equivalence of 11 reales and 2 maravedis. Thus, when the independence movement of the American territories exhausted the source of metal reaching the peninsula, the problem worsened. The kingdom was dependent on silver coins arriving from Europe, especially from France.

The first absolutist reign of Ferdinand VII was abruptly interrupted by the Riego persecution of 1820. This persecution re-established the Constitution of Cadiz and led to a liberal three-year period, until in 1823, an army sent by the King of France, the "100,000 sons of Saint Louis", established another ten-year absolutist reign.

The liberal government of this three-year period embarked on a monetary reform. One of the objectives was to eliminate the dependence on the French currency, and therefore its circulation was prohibited. The collection and re-stamping of silver escudos or half-louis was ordered, thus creating the 10-real coin of Ferdinand VII, which is the subject of this article. In trade, only the re-stamped coin would be accepted, and the unre-stamped one should be used as casting paste. (Decree of November 19, 1821).

As a result of this decree, four minting centers were opened throughout the kingdom, in Madrid, Santander, Bilbao and Seville. Two of these centers were in the north, in Bilbao and Santander, since the use of foreign coins was widespread in these territories. As we have said, the machines from the Segovia mint arrived at the Bilbao mint, and although the year 1821 appears on the obverse of the coin, the minting work was carried out between January and June 1822.

The re-stamping did not require new pre-struck coins or coin-puddings, as the coins were the same half-Escudos, without having been previously minted. Before the coins or coin-puddings were placed under the flywheel press and stamped, they had to be weighed, justified, those lacking in weight separated, cut, superimposed, rubbed with sand, and fenced. However, on a small number of coins, traces of pre-revolutionary Bourbon images and texts can be discerned.

Oh, and the citizens who brought their coins to be re-stamped received 10 billion reales and 10 maravedis in coins… and the remaining 26 maravedis in credit notes. This data is also very significant… and I would like to know how many people collected these credit notes!

Bibliography:

FORO IMPERIO NUMISMATICO – In-depth study of the writer Txibis – link

FORUM IMPERIO NUMISMATICO – Marques de la Ensenada Writer Data – link

LES MONNAIES FRANCAISES ROYALES – Tome 2 – 2° Edition -1999 -Jean Duplessy (In Memoriam 1929- 2020)

De la livre au franc – Guillaume Nicoulaud – 2015 – link

Création du franc Germinal – Évelyne Cohen – 2003 – link

LE PASSAGE DE LA LIVRE TOURNOIS AU FRANC – Société Numismatique Héraldique et Sigillographique du Nord de La France – link

The monetary reform of the liberal three-year period in Spain, 1820-1823: modernization and limits - Enrique Prieto Tejeiro, Dionisio de Haro Romero – 2012 – link

All personal data collected on this blog will only be used to disseminate the contents of this blog. Personal data will never be transferred or sold to third parties. You can unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the link in the footer of our emails.

Pingback: One of the French to appear on Basque coins | History of Basque Coinage

Pingback: Spanish was one of the languages that appeared on Basque coins | History of Basque Coinage