Another very important contribution of Henry II was his support for the creation of written Basque literature. After the priest Bernard Etxepare wrote “Linguae vasconum primitiae”, the first book to be printed in Basque, it was published in Bordeaux in 1545, after receiving financial support from Henry.

The only known copy of Linguae Vasconum Primitiae, kept in the Bibliothèque de France in Paris

To understand the importance of this event, we will analyze the situation of Basque in the lands of the Kingdom of Navarre, during the Old and Middle Ages. To do this, we will use as a basis the 1995 study “Las Lenguas escritas y habladas en Pamplona” by Jose Maria Jimeno Jurio.

It shows how foreign and immigrant peoples, such as the Roca people, had their own writing systems and codes. The Basques did not have these native writing codes and the consequences of this event were profound for Basque.

During Roman rule, the Latin language, brought from abroad, was considered a cultured language accepted by a powerful and wealthy minority and was used in all relations between the local authorities and the metropolis.

After a few centuries, the Romance languages, Occitan, Navarrese Romance and Spanish, replaced Latin. These Romance languages were used in all official documents written by royal and episcopal chancellors and canonical writers.

Basque, which has its origins in the region and predates Latin, remained an unwritten language until the Renaissance, despite being the language of the majority and the people. In the absence of literacy and a graphic system, Basque was socially marginalized and was considered a common and trivial language.

We will not find any documents written in Basque in any of the archives or archives of kings, bishops, municipalities, parishes or monasteries. But it would not be reasonable to conclude that Basque was not spoken in Navarre. At most, we can conclude that it was not written in Basque.

The Basques were the overwhelming majority in the diocese of Pamplona at least until the 17th century, but were considered a lower social class. “Navarra” has the meaning of vagrant in the writing of the Fuero of Estella of 1164 and the meaning of clumsy and peasant throughout the writings of the 13th century. In the urban areas inhabited by the Franks of the north, the Navarrese were a marginal social group, without the rights of neighborhood of the burghs and included in their Navarrese. Their “basconea lingua” or “Lingua navarrorum”, “lingua rusticorum”, “rusticum vocabulum” or “lingua vulgaris” was considered.

The spread of Basque in the Kingdom of Navarre in the 16th century

This has been the true misfortune of Basque up to our days. Despite being the language of the majority, written evidence has concealed not only its spread, but its very existence. When we write the history of our people, we do so using documents written in a language that was not that of the majority. Basque only appears in a few words or short phrases, within texts written in Latin or Romance.

Carmen Saralegui acknowledges the following in her research on Navarrese Romance: that although Basque is the everyday language of the majority of the kingdom's population, it is rarely found in writings and documents.

In the last quarter of the 11th century, and after the successful attempt at Jaca during the reign of Sancho Ramirez, the Franks from the north settled in selected towns along the Camino de Santiago. They brought with them Languedocian Occitan, a koine or standardized language, a kind of “unification” of the different Romance languages spoken in what is now southern France. This language allowed speakers of the different Latin dialects north of the Pyrenees to understand each other.

Occitan, as a written language, was imposed for three centuries, from the 12th to the 14th centuries. It is very likely that a group of citizens of Pamplona spoke Occitan, but in any case, it did not leave any trace in the medieval toponymy of the city. Regardless of the number of speakers, and despite its official status in the Navarrese chancelleries, by the year 1400, Navarrese Romance had replaced Occitan.

Navarrese Romance was born around the 10th century in the territories of the outer regions of the kingdom. On the one hand, in the monasteries of Albelda and San Millán de la Cogolla, which were in the Rioja territories conquered by Sancho Garces. On the other hand, in the areas of Leiria and Sangótza, it was interspersed with features of eastern Aragonese. Little by little, many features began to diverge from the original Latin, until a true dialect was born. And this dialect was absorbed by the “scriptore”, clergy and lords of the itinerant court who moved from one part of the kingdom to another.

In the 13th century, many documents began to be written in Navarrese Romance, and it gradually replaced Latin and Occitan, as the cultured writing and language spoken by a section of the population. The general charter was written in Navarrese Romance. Latin and Navarrese Romance were used at the coronations of Charles II (1350) and Charles III (1390). The minutes or documents of the assembly, written in Latin, record the oaths taken by the king and his subjects. The oaths were pronounced in Navarrese Romance, that is, “in idiomate Navarre terre”, in a learned Romance language that suited the solemnity of the moment and the nobility of those gathered. In an event of this type, and given the socio-economic level of those present, the use of a “common” language such as “lingua navarrorum” or Basque was unthinkable in the mindset of the time.

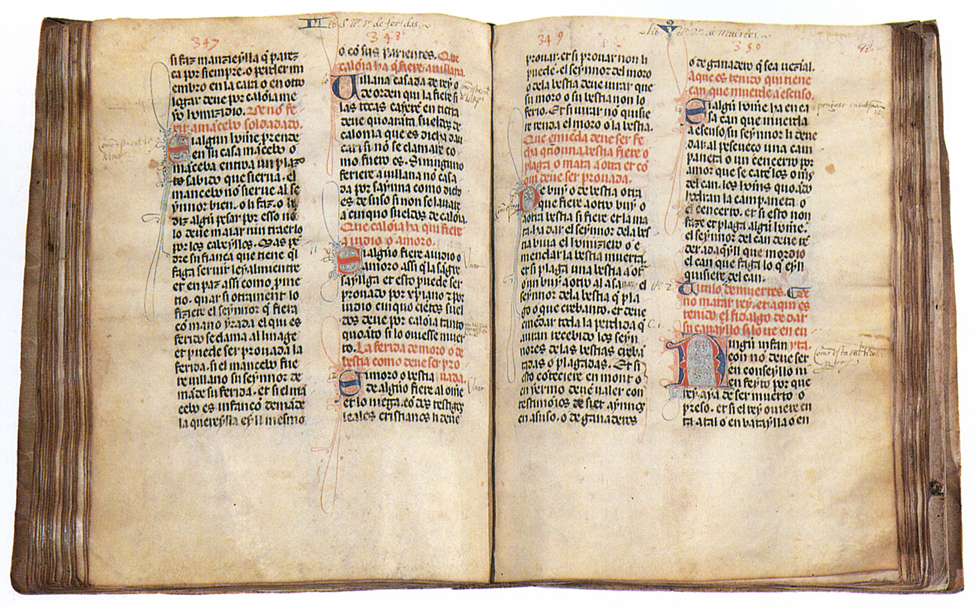

General Charter of Navarre, written in Navarrese Romance – 14th century manuscript

As a result of its internal evolution, Navarrese Romance ended up merging with Spanish during the second half of the 15th century, until it almost completely disappeared after the conquest of the kingdom (1512-1522). The same Henry, faced with the new reality of his kingdom consisting of territories north of the Pyrenees, established Béarn as the working and administrative language, replacing Navarrese Romance.

As we have said, if we pay attention to the languages that appear in the writings, we might think that in medieval Navarre, only Latin, Hebrew and the Romance languages Navarre and Occitan were spoken. But these written languages hide another reality from us: the majority of the population spoke Basque, which did not have a written form. If we started looking for official documents written in Basque, we would be mistaken, but if we started looking at the names given to the fields cultivated and the areas crossed, we would complete and conclude the true picture.

XIV. eta XV. mendeetan zehar, nafar jatorria zuen Iruñako biztanlegoak, bai noble eta bai xumeek, euskeraz hitzegiten zuen ia bere osotasunean. Sektore bat, again gehiengoa, elebiduna (euskera eta erromantzea) zen, edo again eleanitzduna (euskera, erromantzea eta latina). Nafarroako gainerako lurraldeetan, euskeraren nagusitasuna oraindik argiagoa zen, eta biztanlegoaren %80-ak euskeraz hitzegiten zuela irizten da.

Henry II knew several languages from a young age. He spoke Bearn (a dialect of Occitan), the official language of the court of the lordship of Bearn. He also knew Navarrese Romance, the language of documents written during his time as the king's representative in Pamplona. He also knew French, a language he would greatly improve his knowledge and use of during the years he spent at the French court from a young age after the conquest.

In addition, we can say that he acquired knowledge of Basque from an early age with little fear of making a mistake. There is no document that confirms this, but the long periods spent in Pamplona and the data about his education suggest this. Likewise, when reorganizing and establishing the institutions of the territories recovered in Lower Navarre after 1524, he established that public officials had to speak Basque.

And as we mentioned, towards the end of his reign, he sponsored and financed the publication of the first known book in Basque. The book was written by Bernart Etxepare and published in Bordeaux in 1545.

Bernart, who was from the area of Saint-Jean-de-Luz, apparently came from a Beamon family, and as a result supported the invasion of the Castilian troops. At some point during the upheavals of the war between 1516 and 1529, after one of the retreats of the Castilian troops, he was summoned to the court of the King of Navarre, and apparently spent some time in prison, accused of what would now be considered collaborationism or outright treason.

In any case, as the cover of the book states, the book was published in 1545, when he was rector of Saint Michel. When Joanes Leizarraga published his translation of the New Testament in Basque in 1571, he used a “batua” form composed of the three Basque dialects of the North; however, Etxepare used the Navarrese-Lower Basque dialect of his native land when writing the first book in Basque, “Linguae vasconum primitiae”.

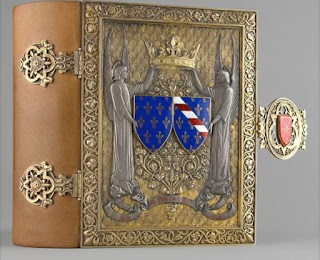

The only copy of the “Linguae Vasconum Primitiae” preserved in Paris. This book was part of the library of the Prince-Count of Bourbon (brother of King Antonio of Navarre). Perhaps a gift from his brother, the coat of arms of the House of Navarre can be seen in the book depository.

To Bernard Lehete, lawyer for the King of Navarre, as Etxepare requests:

"As noble and natural gentlemen, you have esteemed, exalted and honored me, I send you as my lord and master a copy of my manuscript, made according to my ignorance. Because, sir, if you think it is pleasing to you to have them printed, and from all your manuscripts I have a beautiful jewel that has never been printed before (…)"

As I understand it:

"As a noble and natural gentleman (of this town), you do appreciate, exalt and honor the Basque language, I send you as my lord and master some Basque couplets, composed according to my ignorance. Because, sir, having seen and corrected them as you please, if you think it appropriate, you can have them printed and from your hand, we can all have a beautiful jewel printed in Basque, which has never been seen before."

The goal of Etxepare and the royal court of Navarre is clear in the poem “Kontrapas”:

"The Town of Garazi/

May it be blessed/

He gave it to the Basque/

You need a thorn. /

Basque, /

Go out to the square!

/Other people thought/

You can't write/

Now they have tried/

They were deceived. /

Basque, /

Go out into the world! /

If only you were still here/

Without printing, /

You could be engrossed/

From all over the world/

In Basque!”.

Bibliography:

THE LAST BASQUE HEAD OF STATE – Aitzol Altuna – Nabarralde – link

The languages written and spoken in Pamplona – José María Jimeno Jurío – 1995 – link

BERNAT DECHEPARE – WIKIPEDIA – link

EITB – BERNAT ETXEPARE AND THE VIDEO OF THE BOOK STORED IN THE BNF – Kike Amunarriz- link

All personal data collected on this blog will only be used to disseminate the contents of this blog. Personal data will never be transferred or sold to third parties. You can unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the link in the footer of our emails.