Victory: Charles VII of Bourbon and Austria-Este, Carlist king, Second Carlist War

Type: 10 Pesetas centimos

Year: 1875

Mint: Oñati, Gipuzkoa. Series of 100,000 copies, between October and December 1875

Border: Flat

Metal: Copper or Bronze

Diameter: 30 mm

Weight: 10.0 g.

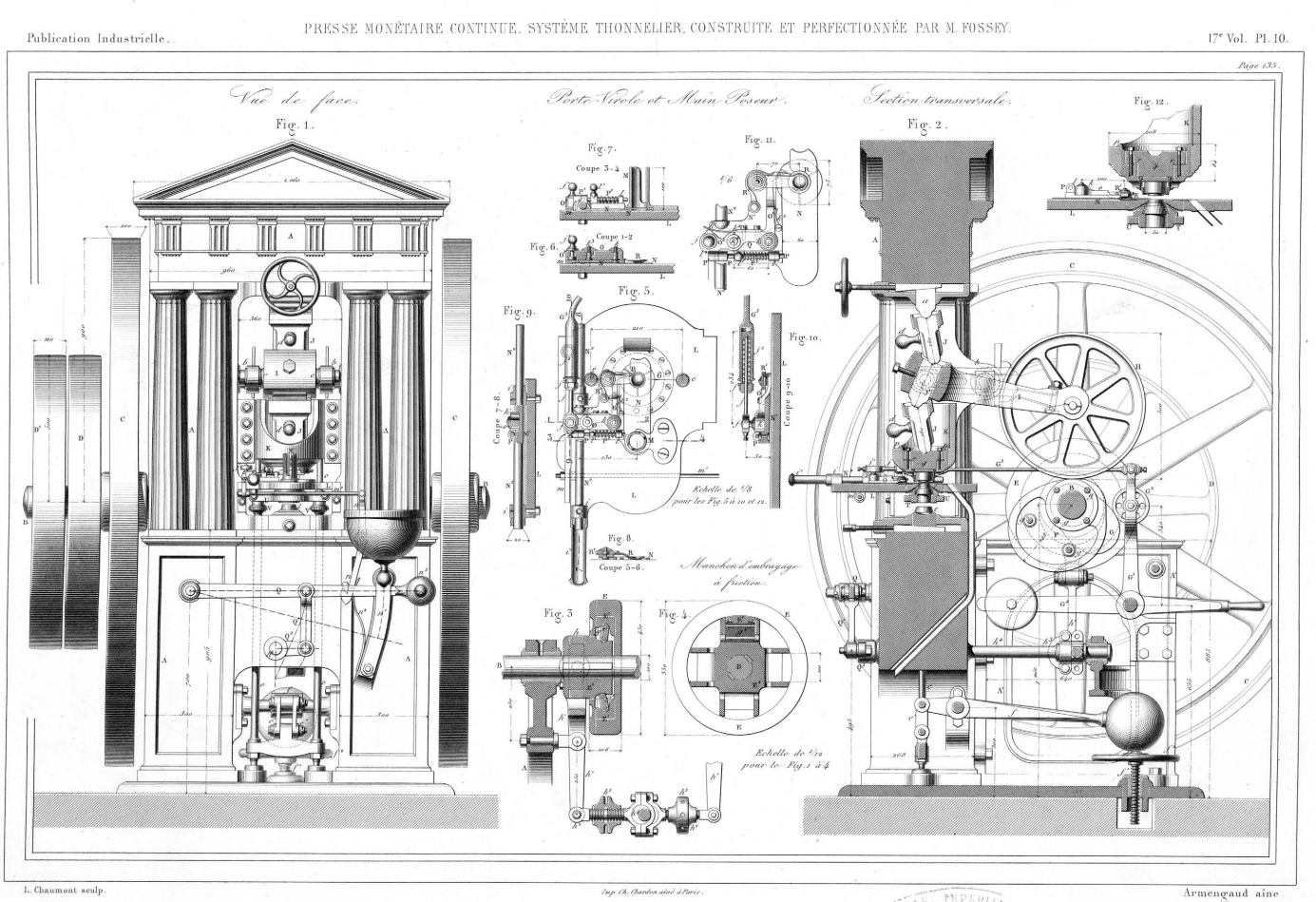

Coinage: Coinage Machine, perhaps by Thonnelier or Thonnelier-Fossey Press

Mintmaster: Unknown, initials OT, perhaps as a reference to Oñati

Recorder: Unknown, initials OT, perhaps as a reference to Oñati

Front:

Obverse Words: – CARLOS VII PL GRACIA DE DIOS REY DE LAS SPAINAS, a lily flower at the beginning of the motto.

Obverse Description: Laurel-clad bust of Charles VII, facing right, with the OT sign below the neck, perhaps the engraver's, perhaps a reference to Oñati, meaning unknown. A circle of pearls surrounds the portrait, surrounding the above-mentioned image text or motto.

Frontispiece: Charles VII, by the grace of God, King of Spain.

Back:

Back Words: – 10 CENTIMOS DE PESETA, 1875 between a lily and a daisy

Description of the Reverse: Below the royal crown, the Coat of Arms of Castile and Leon (an abbreviated coat of arms of Spain) and in the middle, the small coat of arms of the House of Bourbon, with the emblem of Granada below. Around the base of the shield, an open laurel wreath. On the edges of the shield, two crowned anagrams of C7 (of Charles the Seventh). Around all these elements, a circle of pearls, surrounding the above-mentioned image text or motto. Around 1875, a lily and a daisy (Margarita) flower, the latter in honor of the future king's wife, Margaret of Bourbon-Parma.

—-

After some military successes, and with the support of a large part of the population of the Southern Basque Country, the Carlists tried to consolidate the fledgling small state. Charles VII, from mid-1873 to early 1876, ruled de facto over most of the southern Basque Country. In the capitals, the Navarrese coast and a few towns remained liberal, such as Irun, Getari or Hernani in Gipuzkoa. A stable government was organized with its capital in Estella, where the ministerial structure included the following departments: Government, justice, education, provincial councils and general assemblies, press and war. The Penal Code was published, the Supreme Court of Justice, customs, postal service, etc. In Oñati, after reopening the university in 1874, the royal mint was located in 1875. As a symbol of his sovereignty, Don Carlos ordered the issuance of currency.

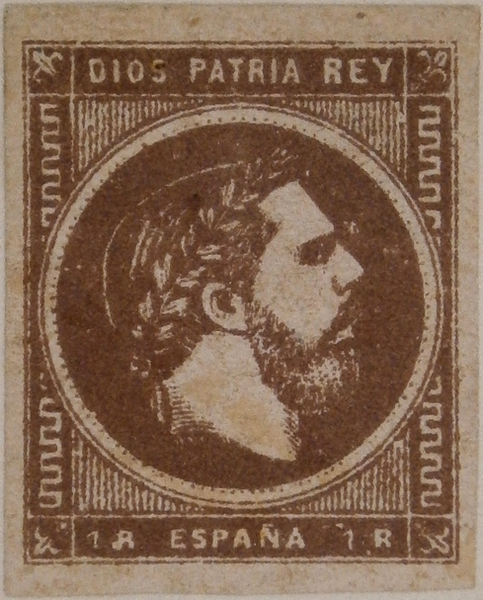

Postage stamp of Charles VII from the Southern Basque Country

The coins minted during the Second Carlist War were minted in two mints and for very different reasons: on the one hand, those officially minted in Oñati; and, on the other, the expensive and controversial silver duros minted in Brussels with the portrait of Charles VII. The latter, as far as we know to this day, were not issues authorized or ordered by the Carlist Government.

The 5 and 10 Pesetas centimo coins, the only ones officially issued by the Carlists, were minted in Oñati between October and December 1875. To the best of this author's knowledge, these are the only official coins ever minted in Gipuzkoa.They are still listed in numerous catalogues and publications as being made in Brussels (the auction where this particular copy was purchased was listed as being made in Brussels), but today it is fully proven that they were made in Oñati.

5 cents of Charles VII – Oñati Mint 1875 – 25mm – 5 gr OT letters

Another copy of the 10 centimes of Charles VII – Oñati Mint 1875 – 30mm – 10 gr OT letters

The definitive proof that these coins were minted in Oñati is found in the order published in the newspaper “el Cuartel Real”. In Tolosa, on December 18, 1875, in issue 318 of the official Carlist newspaper of the time, the following appears:

"Secretariat of State and Treasury Department

Royal order

silent Sr.: SM el Rey (QDG) has agreed to put into circulation the bronze coins of 10 and 5 peseta centimos, minted in the Royal Mint of Oñate.

Lo que de Real orden I communicate to the VSI for its intelligence and consequential effects.

Dios guarde a VSI muchos años.- Real de Durango December 15, 1875.- El Conde del Pinar.- Illmo. Sr. Treasurer General of Castile."

Both coins were made of copper or probably bronze; lead proofs are also known. The 5 centimes has a diameter of 25 mm and a weight of 5 grams, and was minted in a series of 50,000. On the other hand, the 10 centimes, with a diameter of 30 mm and a weight of 10 grams, had a series of 100,000. In both cases, the edge is smooth.

These coins, from 1865 onwards, were created around the French Franc. Latin Monetary Union They are designed and made according to the standard. The peseta, when it was created in October 1868, was created according to this standard (although it was not officially a member of the union). The Carlist coins have certain similarities in design with the coins of the same value, weight and diameter issued by the French governments and the Spanish provisional government at that time. But in terms of design, I can see the greatest similarity with the 5 centimes coin of the shield of Isabel II, although these 5 centimes did not follow the standard of the Latin Monetary Union, and consequently had different weights and diameters.

Napoleon III 10 Franc Centimes – 1865 – Paris Mint – 10.0gr – 30.0mm Diameter

10 centimes of the Peseta of the Provisional Government – 1870-1876 – Barcelona Mint – Oeschger, Mesdach & cia – – 10.0gr – 30.0mm Diameter – Known among the Basques as the Big Dog

French Third Republic 10 Francs – 1870 – Paris Mint – – 10.0gr – 30.0mm Diameter

5 centimes of the Shield of Isabel II – 1868 – Jubia Mint – 12.5 gr – 32.0 mm Diameter – Oeschger, Mesdach & cia

The centimes of Isabel II and the provisional government were made by the company Oeschger Mesdach & cia, under contract to the Madrid government.

In the case of the two coins of Don Carlos, variants with the reverse rotated 180 degrees with respect to the usual position of the dies can also be found. Likewise, most of the specimens have a defect on the reverse, especially in the base of the crown and/or the central shield with the three Bourbon lilies; this is the result of a defect in the die, and not of wear caused by use. In fact, since they were coins issued towards the end of the war, they saw little use and many of the coins were kept as souvenirs.

This particular copy of mine does not show much of the defect described at the base of the crown, but it clearly shows the relief defect mentioned in the shield of the three lilies. It also lacks the letter T from the letters OT, which correspond to the engraver or mint, below the image of Charles VII.

The Royal Mint was opened in the matchbox factory of Mr. Cornelio Garay Zuazubiscar in Oñati, after Mr. Cornelio, a liberal, left the city in 1874 and took refuge in Valladolid. The current company “Hijos de Juan de Garay” (Juan was also Mr. Cornelio’s son) is still located on the same land as the original matchbox factory.

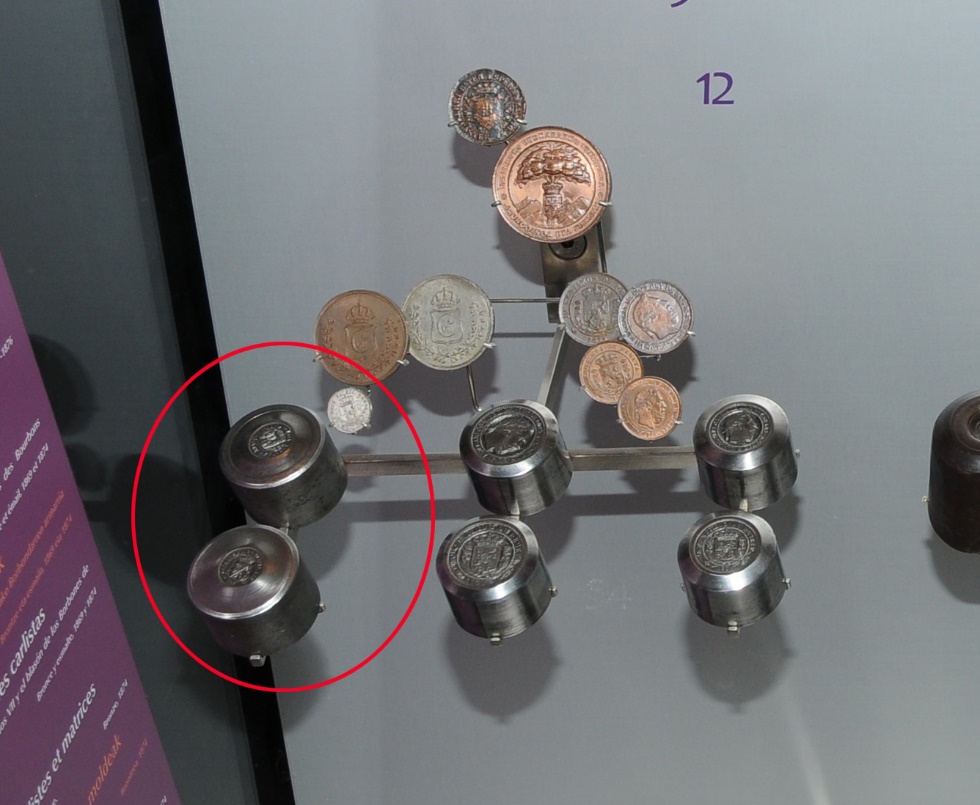

All the material from the Oñati mint was seized by the Alfonsinos when they took the town of Oñati on March 3, 1876. Before this event, the dies for the commemorative medal known as the “Carlist duro” also seem to have been accidentally destroyed. Today, the dies for the 5 and 10 centime coins made in Oñati can be seen in the Basque Museum in Bayonne. Bayonne was one of the most important logistical centers for Carlism in the south of France, and the dies remained there after the Carlists lost the war and went into exile.

The “Carlist duro” of Oñati mentioned above is a medal made by Don Carlos in October 1875 in honor of the opening of the royal mint. The reverse of this medal clearly refers to this event. The obverse shows a crowned coat of arms. Inside this coat of arms is the engraved anagram “CVII”, surrounded by an open crown of laurel and olive branches. The medal was issued in silver and copper, and three variants with different sizes of coats of arms are known.

The size and weight of the medal (diameter 37 mm and weight 25 gr) were the same as the silver duros of the time, and as a result, at the end of the war, although they did not carry the written value of 5 pesetas, they managed to circulate in their form for a limited time. For this reason, they are called “Carlist duros”, and this is how they are described in the description of a specimen on display at the National Archaeological Museum in Madrid.

Medal created in honor of the opening of the Royal Mint of Onati. Also known as the "Carlist duro".

As we have already mentioned, in addition to the coins from Oñati, the controversial duros minted in Brussels with the portrait of Charles VII are also often seen at auctions. The name of Mr. Auguste Brichaut (Brussels 1836 – Paris 1897) always appears in connection with these coins. Brichaut, a civil engineer by profession, was the assayer or inspector of the Brussels mint between 1866 and 1873. A member of the Royal Numismatic Society of Belgium, he became the society's librarian between 1870 and 1874. At the end of these years, in 1873, it seems that he moved to Paris, and as we will see, he worked as a contractor or intermediary in numerous coinage and medal projects.

He had very close relations with the engraver Adrien Hippolyte Veyrat (1803-1883) and the silver and medal workshop of Jean Baptiste Würden (1807-1874) and his son Henri Charles, and it is very likely that the three coins of 1874 presented below are the work of this trio.

Where did the connection between Brichaut and the Carlists arise? The first connection seems to be in the commemorative medal issued by the Carlists after the capture of the Catalan city of Berga in 1873. As can be seen, the portrait of Don Carlos, which appears on this medal, will be reused on the Brussels coins of 1874.

But the Berga medals, according to the memoirs of María de las Nieves, sister-in-law of Charles VII, did not originate in Brussels, but were supposedly made in Austria.

Commemorative medal created after the Carlists took the city of Berga – Copper 34mm 18.37gr – around 1873

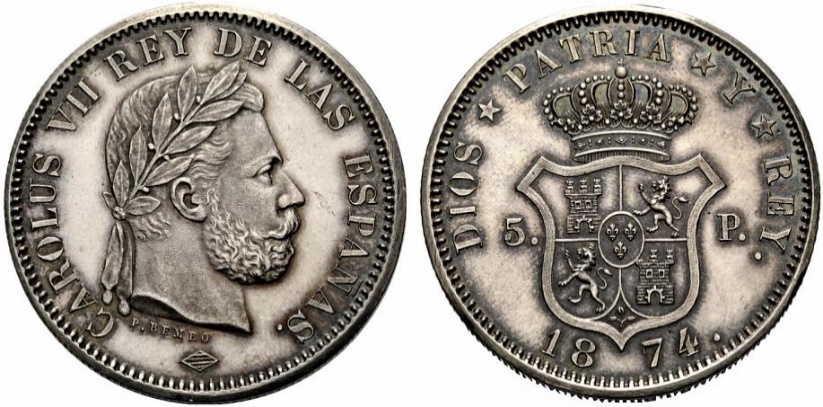

Three different types of coins dating from 1874 feature the same portrait as the Berga medal. In one case, they feature Latin inscriptions (although GRACIA is used instead of GRATIA), or a combination of Latin and Spanish.

Below the portrait, the name of the imaginary engraver P.BEMBO appears. This nickname could be that of the engraver Veyrat or of Brichaut himself. Veyrat was an engraver at the Brussels Mint in Belgium and therefore the use of the nickname would be normal. On the back, they depict the abbreviated coat of arms of Spain from the time of Ferdinand VII, the value of 5 Pesetas, in some cases the small shield of Catalonia and in others the Carlist motto “DIOS, PATRIA Y REY”.

5 Pesetas or duro of Charles VII minted in Brussels. 1st Issue – 1874

5 Pesetas or duro of Charles VII minted in Brussels. 2nd Issue – 1874

5 Pesetas or duro of Charles VII minted in Brussels. 3rd Issue – 1874

But what was the purpose of these duros? Some believe that they could have been coins created to reward Carlist supporters or to finance the Carlist party itself. However, in the book “La España Carlista”, published in 1886 (ten years after the end of the war), the Count of Melgar, secretary to Don Carlos, makes his point clear. These duros, made in Belgium, did not have the authorization or approval of the Carlists and were made by their makers with the intention of selling them to coin collectors for a handsome profit.

Therefore, for now, there is no clear connection between Brichaut and the Carlists. Based on what we have seen so far, we can describe Brichaut and his associates as an opportunistic group that created fantasy coins, sold them and made handsome profits.

5 Pesetas or duro of Charles VII minted in Brussels. 4th Issue – 1885

But the fantasies of Charles VII did not stop there. In 1885, King Alfonso XII died young, suffering from tuberculosis, at the age of only 27. He left no surviving heir, but Queen Maria Cristina was pregnant and the child (who would become Alfonso XIII) was due in the next six months.

Once again, instability reigned in the Spanish monarchy and many believed that a new Carlist uprising was imminent. At this moment, Charles VII's Brussels dukes reappeared.

To this duro, maintaining the same portrait as the duro of 1874 (also with the extension of the ribbon of the laurel wreath), Latin iriditexts and the general design of the coat of arms and the back of the Oñati centimo coins were added. There is no mention of the engraver P.BEMBO (Veyrat died in 1883 and they probably had to find a new engraver), and instead a wheat head appears on the front and an E letter on the back. Around the iriditext, they show an outer circle made of lily flowers.

The last part of the same debate would be the rare 50 centimes silver coins of 1876. As can be seen in the image below, this coin has the same Latin pictograph as the 1885 duros and reuses many elements of the 5 and 10 centimes of Oñati; the letters OT, the coat of arms on the back, the lily and daisy, and the anagram C7.

In the 1876 “Revue Belge de Numismatique”, R. Chalon states that it was the coin that was found during the trial period. Somehow, only a thousand pieces were produced in the coinage collection books that were published. After issuing the 5 and 10 centimes coins, it would have been logical for the Carlists to market the 50 centimes value next. But after the Carlists lost the war at the beginning of 1876, they would have had to stop marketing this coin.

This reasoning seems reasonable and would have seemed reasonable to coin collectors of the time. But on the other hand, all the Carlist coins and medals had Spanish pictorial texts and the era of Latin pictorial texts was already a thing of the past. Once again, we might think that we were faced with the work of Brichaut and his colleagues and a series of fantasy coins.

50 cents of Charles VII – 1876 – OT letters

But after writing to the Basque Museum in Bayonne, the Museum assured me that the dies for the 50 centimes coin, along with the dies for the 5 and 10 centimes coins, are in the Basque Museum in Bayonne. Until a few years ago, they were on public display, but today they are in the museum's collections.

Dies of the 50 centimes coin of Charles VII (within the circle) and dies of the 10 and 5 centimes coins – © Basque Museum of Bayonne – Courtesy of the Basque Museum of Bayonne

Close-up image of the Five Pesetas Centimo dies – Courtesy of Reverso12 Leyendo Monedas Blog writer

The close-up image of the five centime dies shows how the coin dies were made. These dies have the same positive relief that the coins would later have. When the dies were pressed into the coin dies, the dies would receive the negative image of the coin. Through these dies, after being struck with a coin punch or a chisel, the coins would receive the positive relief again. However, the dies do not have all the elements or letters that the dies would later have. For example, the die on the back is missing the last number corresponding to the year, which is the number five. The die on the front is missing the initials OT of the minter. These two elements were printed on the dies at a later stage using punches.

The discovery of the dies in the Bayonne museum confirms that the dies of 50 centimes reached the hands of the Carlists of the Basque Country. It could also be evidence of the links between Brichaut and the Carlists. But does it prove that the 50 centimes coins were issued in Oñati? According to experts, the quality of the issue of the 50 centimes coins completely exceeds the quality level of the 5 and 10 centimes coins from Oñati.

Consequently, we can say that the 50 cent coins were not minted in Oñati. It is likely that Brichaut and his colleagues, after carrying out some tests in Brussels, sent the dies and coin models to the Basque Country. The next step would have been to unify and build the final models of the 50 cent coins and dies, so that the minting work could begin at the royal mint in Oñati. But the development of the war and the exile of the Carlists at the beginning of 1876 put an end to all these steps.

Do the connections between Brichaut and the Carlists stop here? So far, we can say that Brichaut could have been a supplier of designs and matrices, but if we throw out hypotheses, another possible connection can be found.

Where did the coin dies or coin dies needed to make 150,000 coins come from at the Oñati mint? Not much information has come down to us about the Oñati mint, but it seems quite clear that the mint did not have the capacity to produce so many coin dies in a month and a half. Therefore, the coin dies for these coins, which seem to have come from abroad, were purchased by the Carlists on the free market, taking advantage of the spread of the Latin monetary union patterns.

As we have said, Brichaut moved to Paris in 1873 and apparently began to have commercial relations with the company Oeschger, Mesdach & cia. Louis-Gabriel Oeschger and Louis Charles-Marie Mesdach The de Ter Kiele Jaunes registered this company in Paris around 1848, having reached a supply agreement with the director of the Paris mint. Auguste Brichaut himself writes the following about the company Oeschger Mesdach & Cia in an 1878 issue of the magazine „Revue Belge de Numismatique“:

"Mr. Louis Mesdach, founder of the Saint-Charles asylum, owns, together with Mr. Oeschger, foundries, rolling mills and a coin factory among the most important in France, as well as industrial establishments in Ougrée, near Liège in Belgium.

For ten years, the company Oeschger Mesdach & Cia has supplied Spain with 6,550,000 kilograms of bronze coins, initially with the image of Isabel II, and then with the image of Spain (the provisional government), with a nominal value of sixty million five hundred and fifty thousand liras.

Currently, it is working on a new contract, for at least 2,500,000 kilograms, with a nominal value of twenty-five million livres and the image of King Alfonso XII. After melting, alloying, laminating, cutting, forging and peeling the metal, in short, creating the coinage or coin puddings, they are first sent by train to Marseille and then by ship to the Royal Mint of Barcelona. There, at the Barcelona Mint, the coins are produced using the company's twenty-eight Thonnelier coin presses.

The factories of Oeschger Mesdach & cia supplied the Italian government with a nominal value of 1,800,000 kilograms or eighteen million livres, in ten-cent coins or coin puddings. The same factories produced coins and bronze, copper and nickel coins for Germany, Belgium, Brazil, France, Romania, Greece, Egypt, Luxembourg, the Papal States, etc.

Brichaut had first-hand information about the activities of the Oeschger Mesdach & cia company. As can be read in the 1993 Revue Belge de Numismatique, in April 1881, the subscription form for the medal in honor of Auguste Bieswal (member of the Royal Belgian Numismatic Society) could be sent in the name of Auguste Brichaut either to 48 rue des Six Jetons in Brussels or to 9 rue Saint-Paul in Paris. However, the latter address is not Brichaut's home address; this is where the headquarters of the company Oeschger, Mesdach et Cie, later called Eschger, Ghesquiere et Cie after L. Mesdach's retirement, is located. Brichaut was the representative and intermediary of the company Oeschger Mesdach et Cie.

It is very likely that Brichaut acted as an intermediary for the 1250 kgr of coin dies or coin dies that the Oñati mint needed to make 5 and 10 centimes coins, and that these coin dies were supplied by the company Oeschger Mesdach and Cie. According to experts, the bronze used in Oñati entered the southern Basque Country from Bordeaux and Bayonne.

We still have one last question. Where did the machine or machines used in the minting of coins in Oñati come from? I would propose two main hypotheses in an attempt to answer this question.

The first possibility is that the minting machines were sold or borrowed by the company Oeschger, Mesdach and Cie. This is a very strong possibility, as the same company had twenty-eight Thonnelier machines in the Barcelona mint at the same time and we must not forget that we do not know what happened to the machines that Oeschger, Mesdach and Cie had there after the closure of the mints in Jubia, Segovia and Seville in 1868. Perhaps one of these ended up in Oñati?

But if we talk about the Thonnelier coin presses, there is a connection between these coining machines and the Basque Country. And this connection will lead us to a second possible option.

Based on the idea of the German designer Uhlhorn, the Frenchman Thonnelier designed his own perfume-operated coin-pressing machine in 1833. After a relative failure in the early years, Thonnelier granted concessions to other companies to manufacture their Thonnelier machines, and so his models often appear under the names of other companies.

An important detail is his relationship with the English engineer Edward Fossey. Fossey worked for him, as head of the workshop he set up in Paris in 1824, and also became his son-in-law. The Paris factory initially made printing presses, and later moved on to making flywheels and coin presses.

In fact, it was Fossey, after learning to interpret some sketches of Uhlhorn's machine that had come into his possession, who created the first prototype of the Thonnelier press around 1834. Since his father-in-law's workshop was not producing the expected results, Fossey left Paris. We do not have the exact year of this event, but in 1847, the workshop located on Rue Trois Bornes still appears under the names of Thonnelier and Fossey.

As we have said, the implementation of the Thonnelier press in France was complicated, which led Fossey to part ways with his father-in-law. In France, the implementation of the Thonnelier press is fixed in 1846, 1849 or 1852, depending on the sources. According to Francisco Paradaltas, the first free version of the Thonnelier press in Spain was made in 1840 by Edward Fossey in the workshops of Valentin Esparo in Barcelona. Later, two other presses of larger size were manufactured in the same workshop, all three for the mint of the Catalan capital. The Esparó workshops merged with the La Barcelonesa factory in 1855-1856, creating the very famous La Maquinista Terrestre y Marítima.

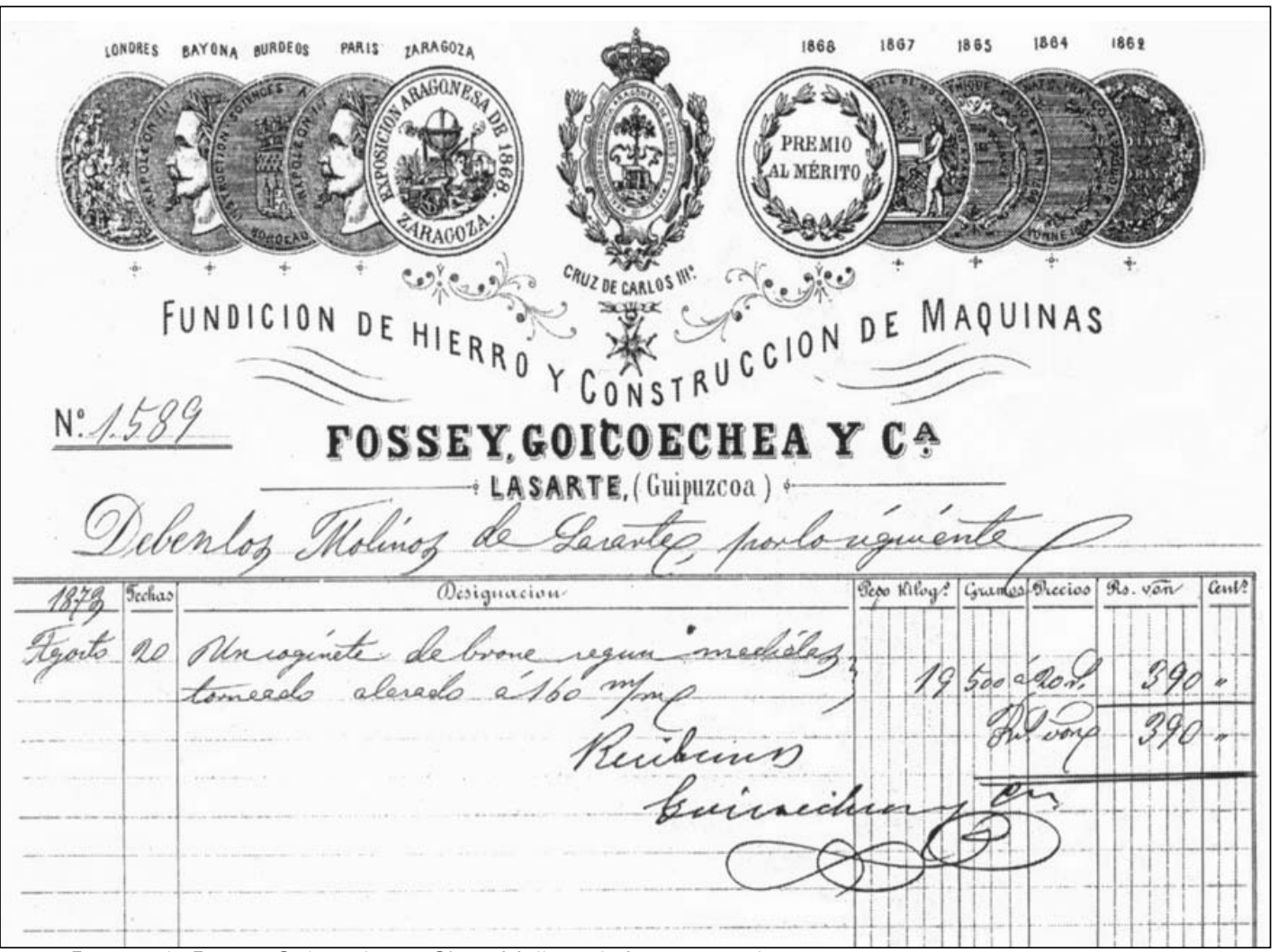

After building the Thonnelier mill in Barcelona and leaving Paris, Edward Fossey, with a Basque partner (José María Arcelus from Lasarte), founded a workshop in Lasarte between 1848 and 1849 to build all kinds of machinery. Initially, the company was called “Construcción de Máquinas de Eduardo Fossey”. Later, after changing the capital, it was called “Fundición de Hierro y Construcción de Máquinas Fossey, Goicoechea y Cía” in 1865. The machines produced by this company were hydraulic presses for extracting oil from olives, presses for making wine, castles, mill tools and implements, and steam engines.

Invoice sent by the company Fossey, Goicoechea y Cia to the company Molinos de Lasarte on August 20, 1873.

But Edward Fossey, who came from the world coin press, in 1867 created a new model of the coin press in Lasarte and presented it at the Universal Exhibition in Paris. There, he made two commemorative medals engraved by Alfred Borrel, one French, with the image of Napoleon III on the obverse, and the other Spanish with that of Isabel II. On the back of this medal, in both Spanish and French, it says: “Medalla acuñada en el palacio por la prensa monetaria de Fossey-Thonnelier y Cia Maquinistas en Lasarte de Guipuzcoa”

Medal of Napoleon III made by Fossey press – Universal Exhibition of Paris – 1867

Medal of Elizabeth II made by Fossey's press – Universal Exhibition in Paris – 1867

Back of Fossey's press-printed medal – Paris Universal Exhibition – 1867

This new model of press (which should not have been named after Thonnelier) brought improvements in the design of the plates, the pressing system, the clutch, and the mechanisms for removing the coin from the ring. From the front, it looked like a Greek temple, with two Doric columns on each side, crowned by a tympanum on a frieze of triglyphs and metopes.

Fossey's press image – 1867 – Aine Armangaud (See Bibliography)

The coin press for the Paris Universal Exhibition was purchased by the Turkish government (the government of the Ottoman Empire). It would be reasonable that, after a period of testing, Fossey's company received an order for more machines.

An article in the Gazette de Biarritz-Bayonne et Saint-jean-de-Luz from 1893 states that Edward Fossey had died twenty years earlier, therefore in 1873. After the war, in 1876, the company no longer bore Fossey's name, but was renamed Goicoechea y Cía.

In any case, in the spring of 1874, in the face of the siege of Bilbao, the position of the liberal troops in Gipuzkoa was reorganized and as a result the Carlists took control of Lasarte. Perhaps after finding a coin press in the local Fossey company, they transported it to Oñati at some point (Lasarte was too close to the front line).

After obtaining the dies and dies through Brichaut's mediation, was it a Fossey machine that created the coins of Oñati at the end of 1875? Unfortunately, I have no data to confirm or deny this statement. Perhaps the future, through new data and documents, will answer all these questions.

As always, remember the good things said, and forgive the bad things said...oh, and let us know when you can.

Bibliography:

DIGITAL NUMISMATICO – THE COINS OF CARLOS VII (1874-1876) – Jesús Martín Alías –link

DIGITAL NUMISMATIC – Carlist decorations during the Third Carlist War 1873-1876 (I) – Jesús Martín Alías –link

DIGITAL NUMISMATIC – Carlist decorations during the Third Carlist War 1873-1876 (II) – Jesús Martín Alías –link

BLOG OF JULEN NUMISMATICA – COINS OF CARLOS VII-CECA OF OÑATI (OÑATE) – Julen Numismática –link

5 CENTIMOS DE CARLOS VII 1875. DOS BUSTOS – LEYENDO MONDAS/NUMISMATICA – Blog de Reverso12 –link

WIKIPEDIA – CARLOS DE BORBON AND AUSTRIA-ESTE – link

WIKIPEDIA – THIRD CARLISTA WAR – link

WIKIPEDIA – MARGARITA DE BORBON PARMA – link

WIKIPEDIA – LATIN MONETARY UNION – link

FORUMS OF IMPERIO NUMISMATICA – Many authors and entries – link

FROM HOUSES OF MONEY TO FÁBRICAS DE NERO. FROM THE VOLANTE PRESS TO THE THONNELLER PRESS – Julio Torres, Museo Casa de la Moneda – link

THE WORKING WORLD OF LASARTE ORIA – Antxon Aguirre Sorondo – 2011- link

Publication industrial des machines tools et appareils les plus perfectionnes et les most recents employed dans les differentes branches de l'industrie francaise et etrangere tome 17 texts et plates - Ainé Armengaud - 1867 - link

THE PESETA: NEW MONETARY UNIT AND POLITICAL PROPAGANDA MEDIUM (1868-1936) – Dr. Jose Maria de Francisco Olmos – 2013- link

REVUE BELGE DE NUMISMATIQUE – R Chalon et L. De Coster – 1875 – link

REVUE BELGE DE NUMISMATIQUE – R Chalon et L. De Coster – 1876 – Page 312-313 – link

REVUE BELGE DE NUMISMATIQUE – R Chalon et L. De Coster – 1878 – Oeschger, Mesdach & Cia – Page 445-446 – link

REVUE BELGE DE NUMISMATIQUE – Many authors – 1993 – Mentions about Auguste Brichaut and Oeschger, Mesdach & Cia – link

AMERICAN NUMISMATIC SOCIETY – David Thomason Alexander – 2015 Issue 3 – Page 38-39 – link

MEDAL PRODUCERS IN BELGIUM (19th – 21st Century) – Stefan de Lombaert – 2015 Issue 3 – Page 38-39 – link

COINAGE – PRETENDER COINS – Numismatic Neverland – David Thomason Alexander – 2015 – From Page 8 – link

CONDECORACIONES CARLISTAS REQUETES – Antonio Prieto Barrio, Jaume Boguñá Borraja – 2010 – link

All personal data collected on this blog will only be used to disseminate the contents of this blog. Personal data will never be transferred or sold to third parties. You can unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the link in the footer of our emails.

Pingback: Louis II – The Last Sovereigns of the Quarter Shields • RIGHT

If you want to know more:

https://leyendomonedasnumismatica.blog/category/carlos-vii-el-pretendiente/